This post originally appeared on the Thomson Reuters Answers On blog.

Supply chain risk is a reality of doing business. Public reporting on how your company spots and addresses red flags over time protects reputations, helps to demonstrate progress and is the honest and responsible way to trade.

These days a product’s supply chain story is as important as the product itself. Companies must publicly demonstrate transparent, accountable supply chains as part of their value proposition.

The reason for change is clear

Today’s highly globalised mineral supply chains have the potential to link companies as well as investors, banks and consumers to conflict and human rights abuses. Whether in Afghanistan, Myanmar, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) or elsewhere precious stones, minerals and other natural resources that are traded and used internationally play a central role in funding and fuelling money laundering, conflict and more.

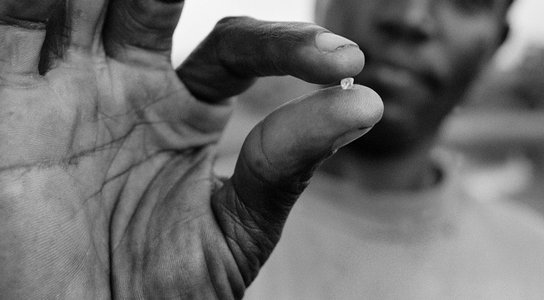

Matandiko Birindwa (45) holds a set of weighing scales that he uses to trade gold, pictured in the village of Mufa II in South Kivu, in the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo on April 11, 2015. Mr. Birindwa has been digging at Mufa since 2004, and has a gold trading house at Mufa. He was targeted in an attack on Mufa in March 2015, but escaped with his assets. Photo: Phil Moore

Whatever their supply chain position, responsible companies that use or trade natural resources must be able to demonstrate what they have done to understand and mitigate risk in their own supply networks.

Tyler Gillard, manager of Sector Projects, Responsible Business Conduct Unit, Investment Division at OECD says: “Transparency is a corner stone of supply chain due diligence, without which companies can’t account to the public, consumers and regulators. We have seen many improvements over the past five years as companies implement the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Mineral Supply Chains but now need to see more: more reports, actual reporting on identified risks and mitigation measures, and reporting on year-on-year progress as companies learn how to carry out supply chain due diligence.”

The OECD Framework

The UN Guiding Principles (UNGPs) require that companies take pro-active steps to ensure that they do not cause or contribute to human rights abuses in their global operations – and respond to any human rights abuses if they do.

Significant international efforts to help companies in this endeavour culminated in the publication of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas. The OECD Guidance translates the UNGPs into a practical five-step framework for companies to use.

Endorsed by 43 OECD and non-OECD countries the Guidance engages the whole mineral supply chain, from mine to end-product, through carefully differentiated obligations based on companies’ supply chain position. It applies to all mineral resources and is global in its scope.

Some countries, like the U.S. and DRC, have already adopted laws that require companies to undertake specific supply chain checks to the OECD standard.

A European Union law designed to ensure that minerals and metals entering the EU are sourced responsibly and without funding conflict and human rights abuses is expected early next year.

What companies must do now

Some companies can already demonstrate progress towards international best practice across their supply networks. A recent survey of 275 US companies found that fifty-one percent had changed the way they manage supply chains in response to human rights concerns.

Globally only a handful of firms actively monitor and address supply chain risk, however.

Fewer still report publicly on their efforts, often leaving their good work unnoticed.

Responsible companies must ensure that they effectively assess supply chain risks by developing robust risk mitigation and management processes, and describing and demonstrating the implementation of those processes in their annual supply chain reports.

Four common areas where most companies must improve their mineral supply chain management and reporting are:

- Report on risk. Acknowledgement of gaps you’ve found and how these are being addressed over time is proof of your responsible sourcing in practice. In other sectors such as apparel this is already done beyond tier 1 suppliers.

- Make it a continuous process. The majority of firms consider supply chain due diligence an annual administrative exercise rather than the on-going, reactive and proactive process that it is. Compliance is a means to an end and not an end in itself. Annual box-ticking leaves your company wide open to risk and is likely to lead to nasty surprises later on.

- Do not out-source supply chain due diligence accountability to a third party. Schemes and services can support a company’s due diligence effort but the ultimate decisions much stay with the company. A recent Global Witness report highlights expensive lessons learnt by investors on the AIM market who wholly outsourced customer checks to nominated advisors (NOMADS) that simultaneously earn fees from companies they bring to market while acting as a watchdog for investors. Paying someone else to make the final decisions for you is often costly in the long run.

- Show improvement over time. This is expected – but it is not a blank cheque. A company must show that it is improving over time. Regular public reporting is the way to do so.

More needs to be done

Despite the commitment to monitor implementation of the OECD Guidance and even where supply chain due diligence laws are in place, some countries are falling woefully short in doing so – failing to ensure that companies meet minimum legal standards.

A recent Global Witness report documents how a private Chinese-owned company – with French and Chinese shareholders – handed out AK47s and cash to armed groups in order to access gold deposits during a gold boom in eastern Congo.

That ‘conflict gold’ was traded into international supply chains. At least part of it was bought by companies in Dubai.

The supply chain and company ownership in this case mean that the Chinese, French, UAE and Congolese governments have responsibilities to act to hold companies and individuals to account for breach of supply chain laws, at the minimum. So far only the Congolese government has taken any public action to hold one of the companies involved to account – and even that is far from adequate.

What you don't know can hurt you

The Congo case study underlines why company supply chain due diligence is so important. Regular supply chain checks to the OECD standard help spot and respond to red flags like those above while protecting and making space for legitimate business.

The OECD Guidance sets an international expectation for more responsible supply chains. Companies must now demonstrate how they put the OECD business model in to practice.

Statements and assurances are cheap when they are light on detail. Companies must evidence what taking responsibility really means to them. By reporting in detail on risk companies can achieve this.