The Kremlin’s increasingly desperate attempts to capture Ukraine by force escalated at the start of the year. Russia’s renewed offensive follows the reported mobilisation of hundreds of thousands of civilians.

Far from the front lines, companies owned jointly by German firm Wintershall Dea and Russia’s Gazprom drill for gas. These deposits in Western Siberia produce a hydrocarbon called gas condensate, which can be used to manufacture a range of fuels, including diesel.

In November 2022 and January 2023, German media alleged that Wintershall’s gas condensate may have produced fuel used in Russian jet bombings that killed dozens of civilians in Ukraine. Wintershall, which is majority-owned by German major BASF, denied the allegations. It accused the press of failing to provide “concrete” evidence of the connection between its products and the Russian military.

Now, a joint Global Witness and RFE investigation, using rail freight data sourced by the Anti-Corruption Data Collective, reveals the supply chains that connect Wintershall’s Siberian gas fields to Russia’s military. We show how gas condensate from Wintershall’s fields in Western Siberia feeds a refinery in Salavat which sends diesel to Russian military suppliers. It is not possible to determine whether any given barrel of diesel from Salavat contains Wintershall’s joint-venture gas condensate. But recipients of that diesel include suppliers of a military unit in the Federal Guard Service (FSO), which is responsible for Vladimir Putin’s personal protection.

In 2014, after Russia invaded Crimea, while Wintershall was expanding its presence in Siberia, its chief executive said: “we’re getting closer to Gazprom...We know that we are good together.” Responding to this investigation, Wintershall told Global Witness that it was not involved in any hydrocarbon transport and marketing in Russia, and claimed there was "no proof that condensate from the Achimov formation has been used to produce fuels for the Russian military for the war of aggression".

Global Witness does not allege direct links between Wintershall’s joint-venture fields and Russia’s military supply chain. But clearly, the connections we have identified are worthy of further investigation. And those deep ties Wintershall cultivated in the Russian fossil fuel industry mean Wintershall cannot guarantee its supply chains are not fueling the Kremlin’s war machine.

Wintershall’s supply chain to Salavat

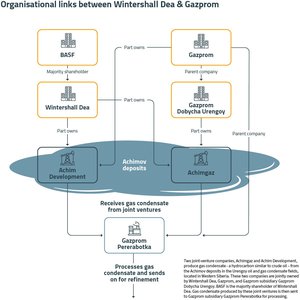

Wintershall has multiple joint ventures in Russia with Russian gas major Gazprom. These include Achimgaz and Achim Development. In January 2023, Wintershall said that state interference meant its assets in Russia had been "economically expropriated." It also pledged to exit the country. But Wintershall’s annual report published in February shows it still owns 50% and 25% of shares in these Russian companies respectively.

These joint ventures extract gas condensate from Russia’s Achimov deposits. Late last year, responding to allegations about Russian jet fuel, Wintershall confirmed that gas condensate is sent from Achimov to a Gazprom subsidiary, Gazprom Pererabotka. Per a May 2022 statement from Gazprom Pererabotka’s general director, Achimov gas condensate is de-ethanised first in a plant near Novy Urengoy before being sent to be processed in its facility in Surgut. The director called these facilities “a single processing complex.”

The Achimov deposits produce a significant portion of the Novy Urengoy plant’s feedstock. In two 2019 press releases, Gazprom Pererabotka stated it received between 4 and 6 million tonnes of Achimov gas condensate annually, and said that it expected that amount to increase. Regardless, 4 million tonnes would represent around one-third of the gas condensate the Novy Urengoy plant processes each year.

Once processed, gas condensate is distributed for refining. In 2022, rail data shows that 66% of the gas condensate leaving Surgut by train went to a station used by a refinery in Salavat, nearly 2 million tonnes. This in turn is almost one-third of the raw material volume that the refinery claims to have consumed last year.

The refinery in Salavat is operated by another Gazprom subsidiary called Gazprom Neftekhim Salavat. It runs primarily on gas condensate – in 2020, the firm said it made up 83% of its feedstock.

Gazprom Neftekhim Salavat has pinpointed the Surgut plant as a source of its gas condensate. Indeed, four years before the invasion of Ukraine, Gazprom boasted of a meeting between Wintershall and Gazprom subsidiary representatives where they discussed Achimov’s gas condensate.

Wintershall told Global Witness that "most of the products marketable by Gazprom Pererabotka remain in the Tyumen Oblast and the Khanty-Mansiysk and Yamalo-Nenets autonomous districts" and that the firm produces "very small quantities of kerosene for civil aviation", without addressing questions on diesel. Yet data in this investigation shows that gas condensate from Surgut, and therefore the Achimov deposits, makes up a portion of Salavat’s feedstock. Any given batch of diesel refined there could have been produced using Wintershall’s joint ventures’ gas condensate.

Sprawling supply chains, military-linked customers

Just months before the war started, the Russian army approved various Salavat diesel products for military use. Around the same time, rail deliveries of fuel from the station next to Salavat to regions bordering Ukraine spiked. Shipments to the border regions continued throughout the war and spiked again in late 2022.

Global Witness and RFE analysis of Russian government procurement records shows that the Salavat refinery in 2022 sent diesel directly to companies with a history of military contracts.

One firm that received multiple deliveries of diesel from Salavat between April and October 2022, Kedr, has signed several army contracts since 2021. It agreed deals to supply gasoline and diesel to military units 38953-K and 69793 in the last two years.

Military unit 69793 is part of Russia’s FSO, which provides personal protection for Vladimir Putin and oversees communications for government agencies. The FSO says these troops operate from the seaside town of Sochi.

The firm that supplied the unit, Kedr, is based in Crimea. Russian media outlets say it operates a petrol station network there under the brand name ATAN. Kedr is well-connected in Russian politics. A state council representative in Crimea from Vladimir-Putin’s ruling United Russia called Igor Tkachenko describes himself as an employee of both Kedr and ATAN. Tkachenko has posted multiple times in support of the war in Ukraine on his VK account, the Russian equivalent of Facebook.

These connections might explain why in March 2023, Kedr signed a contract to supply gasoline to the Crimean Republican Headquarters of the People’s Guards. The Guards are an ex-paramilitary group that played a role in the annexation of Crimea, before forming a public organisation that now provides support to the Russian police.

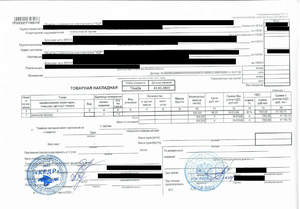

A diesel delivery note between Gazprom Neftekhim Salavat customer, Kedr, and a Russian military unit.

More evidence of military connections to Wintershall’s gas condensate supply chain can be found in the region of Stavropol. Russia’s 49th combined arms army, which has been active in Ukraine, is based there.

Another firm, fuel wholesaler Agro-Snab, signed several contracts to store oil products such as diesel for Russian military unit 2432 in Stavropol from 2014 and through 2017. Rail data shows that Agro-Snab received several shipments of diesel from Salavat in 2022, and received over 550 tonnes in January 2023.

Not far away, a second wholesale fuel company named Promkhim concluded contracts to rent out its diesel tanks to military unit 5559 in 2015. This company received several shipments of diesel from Salavat in June 2022.

The war is probably making it harder to assess where the Achimov gas condensate is going. The Kremlin allows certain government agencies, including the Ministry of Defence, to not disclose procurement information. This rule was expanded on January 1st 2022 to include the National Guard and the FSO. Once gas condensate produced by Wintershall’s joint ventures enters the wider Russian supply network, it appears to become extremely difficult to trace these molecules, and the war likely compounds this.

Wintershall told Global Witness that it rejects our findings. That said, our investigation exposes the features that could connect Wintershall's Russian assets to supply chains in the Kremlin’s war machine. These supply chains, for which Wintershall’s gas condensate is one input, end with companies associated with the Russian military. If investigators outside Russia can establish that, Wintershall can too.

Compensation for…Wintershall?

This evidence raises yet more questions about Wintershall’s presence in Russia. The firm says it has lost control of its Russian joint ventures and shared bank accounts with Gazprom, but it remains unclear when or how it will sell its shares in these companies.

In February, the Financial Times reported Wintershall’s chief financial officer as saying that the company once hoped cash from its Russian operations would be “dividended back” after the war. In the same article, chief executive Mario Mehren declined to comment on whether they would sell their Russian businesses.

Amid the controversy, Wintershall is considering applying for compensation from the German government due to state guarantees for its Russia investments. Given the links Wintershall’s joint ventures have with Russian military supply chains, and the €550m it made in adjusted net income from extracting oil and gas in Russia in 2021 alone, German taxpayers may be surprised to learn Wintershall wants them to compensate it.

Instead of further burdening them, Wintershall should concede it cannot guarantee its businesses have no connection to the Russian military and apologise. Any Russian profits the firm can access rightly belong to the victims of the war, a point made by Ukraine’s campaigners and officials.

Connections to the Russian military should be enough to scare Wintershall off forever. And yet, retaining shares in its Russian ventures leaves the door open for a return to these businesses in the future. The German government should step in and tax Wintershall’s Russian profits at 100% to redirect them to the green reconstruction of Ukraine.

Where possible, the rail freight data has been verified by matching document numbers from wagons to public Gazprom quality certificates that contain details on cargo and sender. For diesel flows, Gazprom Neftekhim Salavat certificates also corroborated the receiver of the product and the train destination station. Additionally, Refinitiv data downloaded in 2022 was used to verify shipments.