Last month, more allegations emerged surrounding the Congolese presidential family’s ill-gotten gains. In Florida, US federal prosecutors took steps to seize a Miami penthouse of Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso, son of Republic of Congo’s president, a sitting member of parliament and former powerful figure in the national oil company, SNPC.

The US prosecutors’ complaint*, seen by Global Witness, adds to an already burgeoning body of material regarding the Sassou-Nguessos’ abuse of power. It comes as the struggling country asks the International Monetary Fund for emergency financial support for the second time in less than a year.

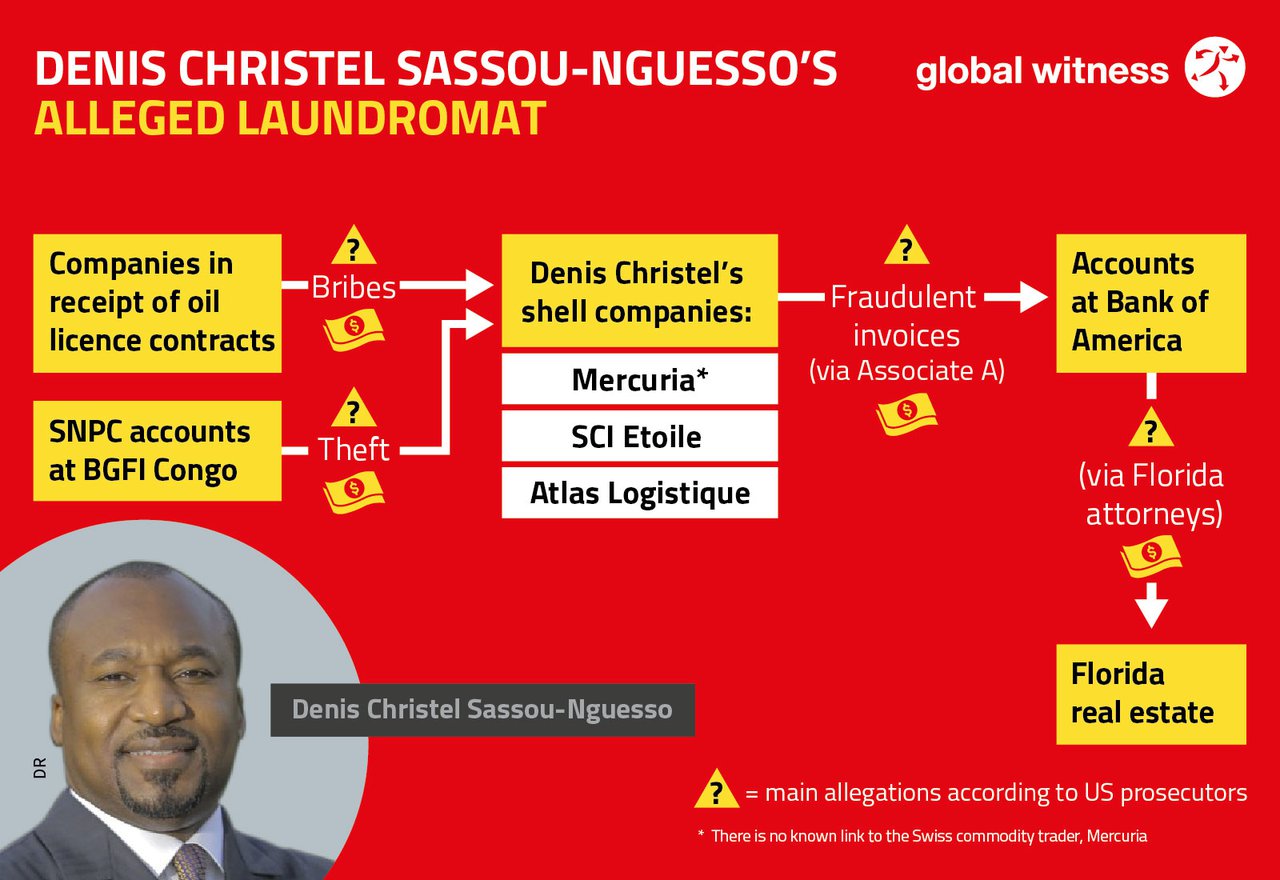

The document details how Denis Christel allegedly embezzled millions of dollars of public funds from SNPC, laundered it through a network of shell companies and used it to buy expensive real estate and luxury goods in the US, France and elsewhere. From 2007 to 2017, Denis Christel spent more than $29 million acquiring assets and paying for his and his family’s lavish lifestyle, according to the US prosecutors – a sum equivalent to around 10 per cent of Congo’s 2020 health budget. He allegedly accepted bribes worth over $1.5 million from oil companies.

Denis Christel allegedly used embezzled and laundered public funds to purchase multi-million dollar real estate, including on Biscayne Boulevard in Miami, pictured above. Jeffrey Greenberg/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

The Florida complaint provides a rare illustration of the full cycle of kleptocracy – how a member of a presidential family allegedly steals, launders and spends public funds for personal gain. The case is an egregious example of how a national oil company could act as a cash cow for corrupt political elites.

Earlier this year, we revealed that

millions of dollars are missing from SNPC’s accounts. Last year, we exposed how

Denis

Christel and his sister, Claudia, seemingly

laundered and spent up to $70 million in stolen state funds. In 2018, Swiss

authorities revealed that Denis Christel

and other Congolese officials received bribes from employees of commodity

trader Gunvor in exchange for oil deals, the subject of a Public Eye investigation. In 2007,

we uncovered how he appeared

to spend $35,000 derived from sales of state oil on designer shopping sprees in

Paris, Marbella and Dubai.

Global Witness wrote to Denis Christel for comment, directly and via the Congolese government’s spokesperson, but did not receive a response.

The Florida allegations

Between 2011 and 2014, Denis Christel allegedly abused his position to embezzle millions from SNPC, Congo’s largest state-owned enterprise and a key pillar of the country’s oil-dependent economy.

![DCSN_shopping_list-1-1[1].png](https://cdn2.globalwitness.org/media/images/DCSN_shopping_list-1-11.width-300.png)

He then funnelled this money into accounts in the names of his various shell companies, including Mercuria (whose name resembles that of the Swiss commodity trader, but there is no known link between the two entities), Atlas Logistique and SCI Etoile, at the Congo subsidiary of BGFI Bank Group, according to the complaint. “Certain [of these] entities are incorporated in Congo, and others in both Congo and France,” the US Department of Justice told Global Witness. The Department added that this remains an ongoing investigation and declined to comment in response to other questions.

"As an SNPC executive, minister, and son of the president, Minister Nguesso was able to simply direct [the CEO of] BGFI [Congo] to transfer SNPC’s (and other public) funds to his own [shell company] accounts. He did so many times,” the complaint reads.

Denis Christel then used a network of bank accounts in the names of these shell companies and nominees to attempt to conceal the misappropriated funds and acquire assets, including the $2.8 million Miami property, another in Coral Gables for $2.4 million in the name of his first wife, Danielle Ognanosso, and others in France. Danielle Ognanosso told French authorities in 2016 that she did not own any US property, and denied knowledge of Denis Christel’s shell company used for this deal.

One of those nominees was “Associate A.”, described in the complaint as a US resident, son of a former Gabonese government official and long-time associate of Denis Christel. Global Witness has been unable to verify the identity of Associate A.

Denis Christel directed Associate A to create fraudulent invoices to explain the transfer of funds, including one for $3,589,543 for “kitchen appliances and other expenses.”

He also opened accounts himself in the US, including four at Bank of America between 2013 and 2016. Using the alias Denis Christelle and a second passport in the same name, he made a minimal attempt to conceal his identity. He allegedly lied about his jobs and income, claiming to earn $50,000 per annum as manager at a company called “Merchurrea” (with notable phonetic similarity to his shell company, and to the Swiss commodity trader Mercuria).

“Bribes and self-dealing”

In addition to misappropriating money from SNPC, “Minister Nguesso also accepted bribes worth over $1.5 million in exchange for awarding lucrative oil license contracts on behalf of SNPC from approximately 2014-2016,” according to the complaint, which does not name any companies.

He further used his position at SNPC “to ensure that companies he had an interest in were granted the status of ‘local partner’ for lucrative oil projects.”

Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso, “the gatekeeper to Congo’s oil wealth” - US prosecutors

Congo issued or renewed twenty-six oil research

and production licences between 2014 and 2016, according to Extractive

Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) reports

and MAETGT,

Congo’s oil registry. The recipients of those licences included oil majors Eni and

Total, among others.

Denis-Christel allegedly embezzled millions of dollars in public funds. He is pictured here with his father, Congo’s President, Denis Sassou Nguesso. Vincent Fournier/Jeune Afrique/REA.

Four of Eni’s 2014 licence renewals are the subject of a recent Global Witness investigation and a Milan corruption probe into the company’s business and choice of local partners in Congo. Global Witness has since reported on a possible $283 million debt write-off by Eni in SNPC’s favour during that same licence renewal process. We have previously written about abuse of Congo’s local content rules to favour politically-connected individuals.

In response to questions from Global Witness, SNPC said that the ministries of oil and finance, the council of ministers and parliament award oil licences, not SNPC’s managers. (Global Witness understands that in practice this is a joint process, which involves SNPC.) SNPC said it would “closely examine” the allegations before responding further.

Eni said that it is not involved in any illegal conduct or corruption relating to certain licences in Congo. It said it conducted an independent audit that did not confirm the corruption probes relating to its Congo licences, which it described as “totally ungrounded and unsubstantiated.”

Total said that it has not paid bribes for any oil licences granted by the Congolese Government. It has undertaken all necessary measures to strictly abide by the relevant anti-corruption laws and its own anti-corruption policy, the company said.

The facilitators

The Florida complaint suggests that Denis Christel used the same techniques and types of facilitators that many kleptocrats and corrupt businessmen have used over the past decade or more.

For every one kleptocrat wishing to

steal, there is an army of enablers willing to conceal, launder and spend – or

turn a blind eye to others doing so. This case allegedly features:

- Nominees – Associate A, Danielle Ognanosso and others who are not named

- A lawyer – an unnamed Florida attorney who handled over $2.3 million from Associate A for the purchase of the Miami property

- Bankers –

- CEO of BGFI Congo who allegedly fielded direct requests from a top official to divert public funds

- Unnamed executives at Bank of America whose anti-money laundering checks failed to identify a top official moving illicit funds through their accounts

Bank of America told Global Witness that it “closed the accounts [in question] in 2017 and cooperated fully with the [US] government’s inquiry into this matter.”

BGFI Group did not respond to Global Witness’ request for comment.

Slow progress: what needs to change

A hospital in Brazzaville. From 2007 to 2017, Denis Christel allegedly spent over $29m on personal luxury, equivalent to around 10% of Congo’s health budget. Alamy.

The Florida complaint is the latest in a series of moves by authorities around the world to trace and seize the ill-gotten gains of Congo’s presidential family, which has been in power for approximately 35 of the past 40 years. In 2015, French authorities seized their luxury property in Paris. In 2019, San Marino authorities seized €19 million allegedly deposited by President Sassou-Nguesso himself.

The complaint and others like it suggest the scope of the problem, but actions to fix it are slow to follow. States must cease to provide a safe haven and playground for the world’s kleptocrats. The global financial system should block, not facilitate, the movement of stolen or questionable funds. Bankers, lawyers and real estate agents must stop making money on the back of citizens elsewhere deprived of access to basic healthcare and an education.

In particular, there must be investigations into and full accountability for all the individuals and companies involved, including but not limited to Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso and his family; Congo’s national oil company, SNPC; the facilitators; and the companies that allegedly paid bribes in exchange for oil licences.

A man holds a placard reading “Congo is not the Sassou Nguessos' [private] property” during an opposition protest in Brazzaville in 2015. Laudes Martial Mbon/AFP via Getty Images.

All relevant jurisdictions should fully cooperate in a timely manner with requests for mutual legal assistance.

The IMF and other multilateral creditors must enforce to the letter the anti-corruption conditions attached to any existing or future financial support to Congo.

Finally, the case highlights once again the importance of public registers of the beneficial ownership of companies and trusts, and of bankers, lawyers and estate agents knowing their clients and the source of their funds. Bankers, lawyers and estate agents must be required to do anti-money laundering checks on their customers, in line with international standards, and sanctioned for failing to do so.

*The Florida complaint was filed on behalf of the United States of America by attorneys in the money laundering and asset recovery section of the US Department of Justice on 12 June 2020. It is a civil application for forfeiture of 900 Biscayne Boulevard, unit #6107.

Find out more

You might also like

-

Briefing Rigged: where has Republic of Congo’s oil money gone?

Our analysis of previously hidden oil sector documents from Republic of Congo reveals major indicators of corruption and a sector skewed in favour of foreign oil companies, including Total, Chevron and Eni

-

Article Trump’s Luxury Condo: A Congolese State Affair

Our new investigation reveals how the Congolese Presidential family used tainted money to buy a Trump apartment in New York City.

-

Article Sassou-Nguesso’s Laundromat: A Congolese State Affair – Part II

The son of Republic of Congo’s President Denis Sassou-Nguesso seemingly stole over $50 million from the Congolese treasury by setting up a complex and opaque corporate structure in multiple countries.