In 2022, a Global Witness investigation revealed a shocking reality at the heart of the green energy transition. Unregulated mines in Myanmar had become an essential source of heavy rare earth elements (HREE), vital ingredients for the magnets used in electric vehicles (EV) and wind turbines worldwide.

China, which controls nearly 90% of global rare earth processing capacity, had in effect outsourced much of its extraction to Myanmar, at terrible cost to the environment and local communities. Most of the HREE from Myanmar originate from Kachin State, on the border with China. Kachin has seen a decades-long struggle between ethnic communities and the Myanmar military for greater political autonomy. After the violent military coup in 2021, the military junta has struggled to maintain territorial control due to strong opposition from the public and armed groups.

Mountains across Kachin bear the scars of rare earth mining. CREDIT: Global Witness

Two years after our last report, we have revisited this region’s toxic mining landscape. New trade data, satellite imagery and community testimony reveal that the world’s dependence on a remote corner of Myanmar has only deepened, and so too have the consequences for the people who live there.

Interviews with local mine workers and community members suggest that the impact on workers’ health, on the environment and on local communities continue to be devastating. One community member in the town of Chipwe said: “There are no longer fish in the waters. Stepping into the water can cause itching and infections. When the animals drink the water, they die.”

We also found that imports of heavy rare earth oxides from Myanmar to China skyrocketed from their previous highs of 19,500 tons in 2021 to reach 41,700 tonnes in 2023 – more than double China’s own quota for domestic HREE mining. Given that limited alternative sources have emerged in the meantime, this further cements Myanmar’s role as the single largest source of vital HREE.

Updated satellite imagery analysed by Global Witness reveals the destruction this demand is driving on the ground. In Kachin Special Region 1, controlled by militias aligned with Myanmar’s brutal military rulers, the number of mining sites has increased by more than 40%, spreading outwards from the border settlement of Pangwa towards Chipwe town. We also identified a sharp increase in the number of sites in Momauk township, a region controlled by the Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO), an ethnic resistance organisation with broad popular support in Kachin that has been locked in a political and armed struggle with Myanmar’s military.

Myanmar’s lucrative trade in HREE – worth $1.4 billion in 2023 – risks financing conflict and destruction in a highly volatile region. In 2018 Myanmar’s civilian-led government banned exports and ordered Chinese miners to wind down operations. Since 2021, extraction has continued in the context of a ruthless dictatorship and widening civil conflict. The vast majority of the country’s extraction is explicitly illegal – controlled by an illegitimate military-aligned militia which, according to Kachin sources, has no regulation on mining standards. The KIO enjoys greater legitimacy, and operates as a de facto government in Kachin.

When contacted by Global Witness prior to publication, a KIO spokesperson said that they had placed “strict rules” on rare earth mining companies in order to protect the environment. However, local sources consulted by Global Witness were not aware of any legal frameworks put in place by the KIO to regulate the industry. On both sides, this largely unregulated mining is environmentally devastating, and the threat it poses to ecosystems and to human health is becoming ever more urgent.

Burning chemicals, poisoned streams

Ah Brang* works dragging bags of acid to the collection ponds at a mine near Pangwa, in Kachin Special Region 1. He stirs it into the water with a stick, protected only by a raincoat and gloves. Sometimes, he resorts to using plastic bags to shield his hands from the burning chemical.

“It feels like you’re eating it when it gets in your mouth,” he said. “It tastes like battery acid. Sour and tangy. Even if you wear a mask near it, your throat burns, and you cough a lot.”

Ah Brang works with oxalic acid — a toxic chemical used to treat the rare earths once they've been drained from the mountainside. The process begins high above the ponds, where ammonium sulphate is injected into the earth through a network of pipes. As the solution tracks downslope it gathers rare earth elements, but not without devastating consequences for the environment. In China, where this technique — known as in-situ-leaching — was first developed in the 1980s, there are widespread reports of polluted watercourses and farmland, and the destruction of vegetation.

In-situ leaching is still permitted in China, but it is now governed by an official production quota, a strict set of standards and an environmental impact assessment process that includes measures to mitigate against acid leakage. No such regulations seem to apply in Myanmar.

Instead, the extraction of HREE is prioritised above all else. New mining operations emerge rapidly and large volumes of chemicals are used to maximise extraction. Trade data indicates that most of these chemicals come from China itself — with exports to Myanmar of 1.5 million tonnes of ammonium sulphate in 2023 (up from 93 thousand tonnes in 2015) and 174 thousand tonnes of oxalic acid (up from 342 tonnes in 2015).

Rare earth mining can leave a trail of environmental devastation. CREDIT: Global Witness

“You can’t plant anything in the fields anymore. Can’t catch fish in the streams anymore. Many animals have died by drinking that water.” - Ah Brang*

The costs are felt by workers and the local

population. Across the mining region, workers complain of

coughing, numbness, skin conditions and kidney issues, all known health risks from the chemical cocktail used in

the mines. Global Witness accessed interviews with the wife and mother of two miners who died

shortly after being discharged from work. Both were suffering from severe

gastrointestinal issues, including ruptured organs and fluid buildup in the

abdomen. Their families were convinced their deaths were caused by chemical

exposure, although neither was diagnosed. One was a newlywed husband and

father. The other was a 15-year-old boy.

“His internal organs were rotten,” the miner’s widow said. “If they explained [about these risks], who would go to work there?”

These toxic chemicals are percolating into the streams where local people once fished and drew water to drink. Recent water sampling data seen by Global Witness showed that several streams in Kachin Special Region 1 are highly acidic and contain elevated levels of arsenic. The contaminated water is threatening to lay waste to a region known as a global biodiversity hotspot, home to an estimated 1,500 species that exist nowhere else, and the largest remaining tracts of primary forest in mainland Southeast Asia.

“Everything is destroyed,” Ah Brang said. “You can’t plant anything in the fields anymore. Can’t catch fish in the streams anymore. Many animals have died by drinking that water.”

And as global demand for rare earths continues to grow, the devastation is spreading.

Rare earth leaching spreads across Kachin

Global Witness previously documented the boom in HREE mining in Kachin Special Region 1 – an area controlled by militias loyal to Myanmar’s military. Satellite imagery now reveals that the number of mining sites in the region has leapt to over 300, an increase of more than 40% between 2021 and 2023, saturating the landscape around the border town of Pangwa. They are now fast encroaching on the town of Chipwe, which residents describe as once surrounded by orchids and wildlife, with small farms growing rice and taro on the banks of Chipwe creek.

“Now, the water turned cloudy, and it smells like metal,” said Naw Naw*, a local community leader. “Houses near the riverbanks have moved away due to the unbearable smell.”

Mining sites in Kachin Special Region 1

This environmental crisis is compounded by escalating social issues. Drug use is rising among local men, as well as violence and petty crime. As prices spiral for basic goods, teenage boys are leaving school to try their luck in the mines, while young women are recruited via ads on social media to provide sexual and domestic services to the Chinese workers that occupy higher-paying roles in the mining operations.

“I don’t want people to come here as your life will get ruined. Men got decimated by drugs and women got turned into mistresses,” a former miner said. He had previously seen the mining as a good way to make money, but now “all my dreams have been shattered.”

Local people described how the militias use a mix of coercion and payoffs to facilitate land acquisitions for Chinese companies, sometimes negotiating with absent village elders who fail to consult or compensate the local population. “Those who sold the mountains became rich,” said the miner, Ah Brang. “But when it’s time to suffer, they dodge.”

“Even for selling [the mountains], there’s nothing left,” he added, explaining that the only unsold lands in the region are now rocky areas where mining is difficult. This view resonates with those of Chinese industry analysts such as Huafu Securities, which observed in early 2024 that “after years of unregulated mining, the mineral grade [of Myanmar’s rare earth exports] has gradually declined.”

As Pangwa’s rare earth bonanza reaches its limits, new parts of Kachin State are coming under threat.

Mining sites in Momauk Township

A hundred miles south, satellite imagery analysed by Global Witness showed that rare earth mines are now rapidly proliferating in Momauk Township, controlled by the Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO). In 2021, the region contained just nine mining sites. By the end of 2023, that number had leapt to more than 40.

Although these operations are still small in number compared to those under the control of junta-aligned militias in Kachin Special Region 1, a local woman stated that the KIO-controlled region has suffered a similar rise in health conditions, as well as drug addiction and sex work linked to the growth of mining. Unlike the militias, the KIO is a major ethnic political organisation with considerable local legitimacy and concern for its public reputation. But the potential income from mining is clearly creating pressure for expansion.

In May 2023, the media outlet Frontier Myanmar reported that local communities had rallied to resist KIO plans to expand rare earth operations south into Mansi Township. Although the KIO eventually backed down and cancelled the project, KIO commander General N’Ban La delivered a speech insisting that the mining revenues had been intended to fund its struggle against the junta. The region is an active conflict zone, which in early 2024 saw a series of clashes between the KIO’s armed wing, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), and Myanmar’s military. The KIO also controls territory in other parts of Kachin state, including a small pocket of rare earth mines in Hpare, 15 miles north of Pangwa.

When Global Witness contacted the KIO for comment, a spokesperson said that, in areas they control, rare earth mining started in 2021 and is currently limited to Munghka district [where Momauk township is located]. They said that when negative impacts arise they stop the mining, that mining only proceeds with local people’s consent, and that “in order not to harm the environment, KIO have regulated strict rules on [rare earth] mining companies”. They added that “income generated from [rare earth] mining is not considered as revenue for the KIO. Usually it is set aside for the regional development fund. This will be spent for education, health and infrastructure development in the region.”

According to Richard Horsey, a Myanmar analyst for International Crisis Group, actors on both sides of the conflict see the potential of HREEs as a major revenue source. HREE mining is “a huge source of income for what is actually quite a small armed group, allied with the Myanmar military,” he said, referring to the militia that controls Kachin Special Region 1. At the same time, “the KIO is definitely interested in developing its own rare earth mines because it sees how much money is being made. It can’t afford not to have a slice of that revenue.”

A global supply chain

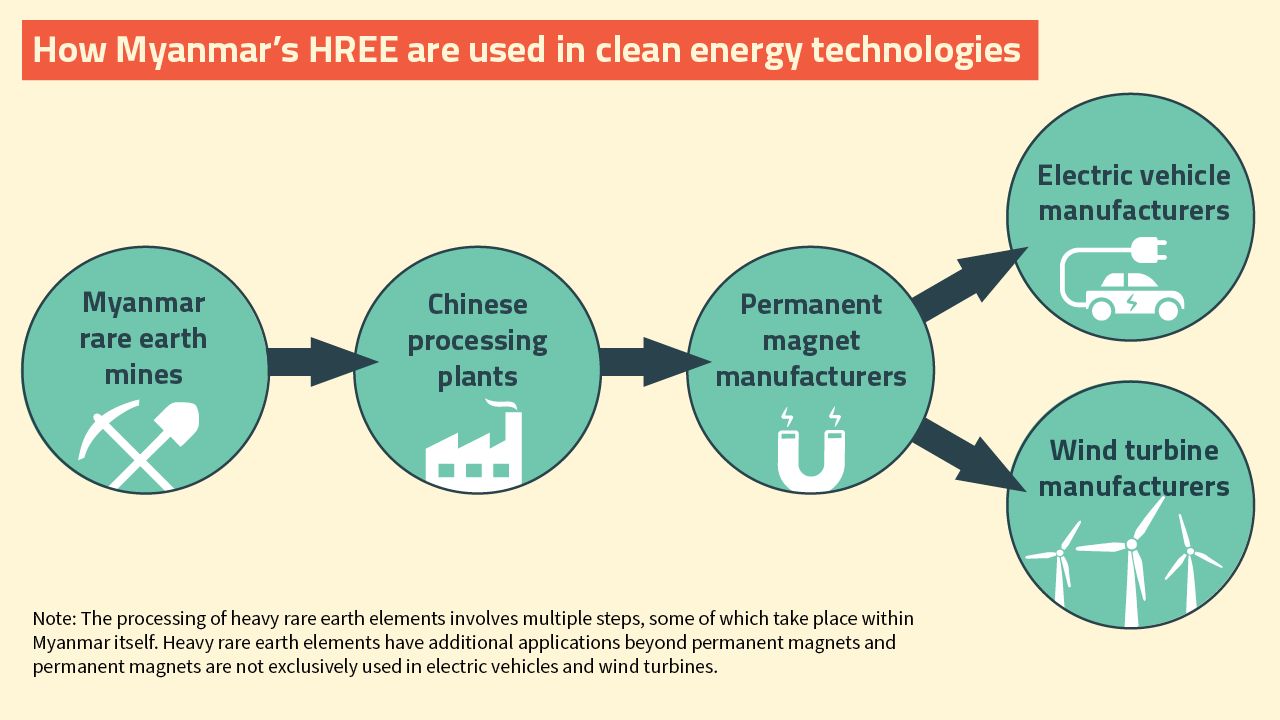

Demand for permanent magnets, mostly used in EVs and wind turbines, is driving the boom in rare earth mining across Kachin state. It appears that Myanmar’s HREE output goes predominantly to rare earth processors in China, then on to magnet manufacturers, before finding their way to EV and wind turbine firms – some of which are household names.

According to industry expert David Merriman, Research Director at consultancy Project Blue, “the use of heavy rare earths originating from Myanmar in EV motors manufactured by many western household brands is almost inevitable.”

The extraction and processing of rare earths is tightly controlled by an official quota in China. Following a period of consolidation, that quota is currently allocated to just two state-owned companies - China Northern Rare Earths Group and China Rare Earths Group (REGCC). REGCC was created by a 2022 merger of existing Chinese rare earths firms, at least one of which previously disclosed sourcing HREE from Myanmar.

Further documents published online by Chinese authorities outline plans for facilities owned by REGCC subsidiaries in Longling and Jianghua to rely on rare earths imported from Myanmar.

When contacted for comment by Global Witness, REGCC said the company “attaches great importance to ESG and supply chain management” and “insists on law-based operation and social responsibilities.” It added that each subsidiary of the group “is an independent legal entity” but that REGCC took Global Witness’ findings seriously and would therefore “form a special team to carry out relevant in-depth investigation and research, and strengthen targeted regulatory measures so that the Group's subsidiaries can better operate with standards and efficiency.”

Rare earth leaching pools in Kachin state. CREDIT: Global Witness

After processing, a significant proportion of HREE is used to make permanent magnets. The vast majority of rare earth magnets - 92% according to one estimate – are produced in China. Two major Chinese magnet makers who are known to have signed rare earth supply agreements with REGCC are JL Mag Rare Earth and Yantai Zhenghai Magnetic Material (also known as ZH Mag).

In company documents JL Mag has boasted of a range of high-profile clients including electric vehicle manufacturing giants Tesla and Volkswagen, as well as major wind turbine makers Siemens Gamesa and Goldwind. Trade data analysed by Global Witness showed that JL Mag made numerous shipments of permanent magnets to Tesla’s Fremont factory outside San Francisco during 2023.

When contacted by Global Witness, JL Mag denied sourcing HREE from Myanmar “whether directly, through suppliers or by any other means”. It said that it sourced HREE from REGCC subsidiary China Southern Rare Earth Group, a firm named in Global Witness’ 2022 investigation into rare earth mining in Myanmar, but that it had requested its supplier "to guarantee that 100% of its heavy rare earth materials come from recycling,” and do not involve materials from Myanmar. JL Mag added that it conducts in-depth environmental and social due diligence into all suppliers as outlined in the firm’s “Code of conduct for sustainable supplier development.”

ZH Mag meanwhile said in its 2021 annual report that it supplied magnets to carmakers including Volkswagen, Toyota, Nissan, Ford and Hyundai as well as automotive parts makers such as Germany’s Brose. It also listed European wind power firms Siemens Gamesa and Vestas amongst its clients. Shipping records show that ZH Mag was also a supplier of magnets to the major automotive parts manufacturer Nidec during 2023.

Global Witness did not find conclusive evidence that the permanent magnets purchased by these EV and wind turbine firms contain heavy rare earths from Myanmar. Nevertheless, the supply chain relationships that exist suggest that a wide range of well-known companies should be concerned about environmental, social and conflict-financing risks, and undertake appropriate due diligence into their supply chains.

Wind turbines often rely on permanent magnets containing heavy rare earths. CREDIT: Dennis Cox/Alamy

Global Witness wrote to all the downstream companies named in this report requesting comment. Most of them did not respond. Of those that did, Brose said: “we have confirmed with our supplier that our products are free of any rare earth minerals sourced from Myanmar. The Brose Group also does not have any active supply relationship with companies in Myanmar.” Nissan told us “We are committed to working with our business partners, including suppliers and contractors, to enhance transparency and traceability in our supply chain.” Toyota said “We are opposed to unsustainable mining practices and any abuses of human rights in general, and we are aware that there is a growing concern that the mining of heavy rare earths, such as terbium and dysprosium, might be associated with certain environmental, social and governance issues,” adding that this was reflected in the company’s Sustainable Purchasing Guidelines. They also said that they would investigate Global Witness’ claims and if necessary would ask suppliers “to make corrective improvement actions.”

A common claim amongst downstream firms is that their magnets come from ‘recycled’ materials. But according to industry analysts Wood Mackenzie, “the vast majority of recycled material is sourced from swarf (offcuts and grinding media generated during magnet manufacturing)” rather than end-of-life products. Such ‘recycling’ does little to reduce the probability that the rare earths came from Myanmar, or to address the myriad sustainability threats in the supply chain.

Looking to the future

The world’s dependence on HREE from Myanmar was laid bare in 2021 and 2022, when concerns about the impact of the coronavirus pandemic and post-coup instability led China to close the Myanmar border. The disruption limited supplies of HREE and caused prices to soar, sending shockwaves through the rare earth industry and sparking international conversations about the security of supply.

These concerns are justified. Myanmar’s rare earth sector is not only environmentally devastating, but also occurring in a context of high political instability. Furthermore, a lack of proper geological mapping in this remote and complex region means that nobody knows how big Myanmar’s reserves are, or how fast they are running out.

Faced with this insecurity, Chinese companies have begun to develop alternative sources of supply in Laos and Malaysia. Imports of HREE from both countries began in 2023, but the total volumes remained small by comparison to Myanmar. Meanwhile, western nations are pushing to reduce dependence on China-controlled HREE supply chains by improving recycling systems and developing mines in countries such as the US, Canada and Brazil. But most of these projects are in nascent stages, and an industry insider has warned that developing more sustainable sources will require paying higher prices for HREE.

As supply constraints and environmental concerns mount, some western firms – including Tesla and General Motors aim to develop technology that would reduce reliance on HREE. But given that HREE hold a performance advantage for manufacturers, analysts predict that demand will continue to grow.

Myanmar’s unregulated mines cannot meet this demand forever.

“The digging around Pangwa has mostly wrapped up; there’s not a lot of mining happening there now,” a former miner said, in comments echoed by others. If the system remains unchanged, depletion of this coveted resource will continue to push Myanmar’s toxic mines into new, previously undamaged areas. With no plans to restore the devastated landscapes left behind, their legacy for communities is bleak.

“Old mining sites are left as is,” Naw Naw said. “There are old shelters, pipes, and plastics, all left as garbage heaps.”

“If the minerals are depleted, what will people do for a living?” he asked. “Nothing can grow there anymore.”

*Names have been changed to protect the identities of people interviewed in Myanmar

A rare earth extraction site, Kachin State. CREDIT: Global Witness

Recommendations

To companies mining or planning to mine heavy rare earths in Myanmar

Halt mining operations, in recognition that they are environmentally devastating and violate international norms. All are operating without a clear regulatory framework and most are explicitly illegal. Implement a responsible exit, including rehabilitating the environment, compensating affected communities, and returning land to customary landholders and local communities.

To KIO local authorities in rare earth mining regions in Myanmar

Stop mining activities until safeguards in line with international standards are put in place that protect local communities and the environment from adverse impacts associated with rare earth mining.

Work with civil society and local communities to develop regulations for responsible mining that benefits the people and protects the environment.

To companies whose supply chains involve heavy rare earths

Adopt and apply the OECD’s Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (OECD Guidance), the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

Apply the OECD Guidance five-step framework when sourcing heavy rare earth minerals or products containing heavy rare earth metals:

- Map rare earth supply chains, identify all processors in supply chains and trace minerals back to the mine.

- Identify human rights, conflict finance, environmental and other risks along supply chains.

- Engage with suppliers and other relevant stakeholders on mapping supply chains and risks in the supply chains as well as mitigating them.

- Develop and implement risk management plans.

- Report in detail on supply chain due diligence including supply chain analysis, identified risks as well as measures taken to prevent and mitigate and remediate risks and negative impacts on an at least yearly basis.

- Following the OECD Guidance, companies should suspend or discontinue engagement with suppliers if there is a reasonable risk of serious human rights abuse and/or conflict finance.

Given the proportion of heavy rare earths extracted in Myanmar and the nature of the supply chains, companies should assume that heavy rare earth minerals in their supply chains come from Myanmar unless upstream suppliers can clearly demonstrate that it was sourced from elsewhere.

Companies producing magnets should use recycled feedstock and look for other sources of rare earths than from Myanmar that fulfil high environmental, social and governance standards.

Companies procuring magnets should where available use, and otherwise invest in, alternative technologies that substitute heavy rare earths and seek a supply that is free from heavy rare earths produced in Myanmar.

To financers and investors in companies that mine, process, or source rare earths

Develop an engagement plan to ensure that companies in receipt of investment are not contributing directly or indirectly to harms related to heavy rare earth mining in Myanmar.

Make public reporting on sourcing a requirement of financial support or investment.

Use leverage, such as the threat of withdrawing financial support, to dissuade companies from continuing to source, directly or indirectly, heavy rare earths from Myanmar.

To industry bodies

Ensure that members carry out supply chain due diligence aligned with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the OECD Guidance, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct and other internationally agreed standards and principles.

To governments

Enforce and, where they are not in line with UN and OECD standards, strengthen existing relevant due diligence regulations such as the EU Corporate Due Diligence Directive, the German Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains or the French Duty of Vigilance Law.

Adopt and enforce legislation ensuring effective human rights and environmental due diligence including strict penalties for non-compliance in countries that do not have respective regulations.

Adopt import restrictions for rare earth minerals produced in Myanmar barring them from entry unless the importer can present sufficient evidence that the product has not been linked to human rights abuses, conflict and corruption and the product was produced legally.

Hold mining companies operating overseas accountable to the same environmental social and governance regulations that apply in their own country as well as the highest international standards. These should include:

- The right of Free Prior Informed Consent (FPIC) of Indigenous Peoples as well as other affected communities.

- Environmental standards reducing the negative impact of rare earth extraction to the maximum possible, e.g. by requiring companies to use alternative, less environmentally destructive methods than in-situ leaching.

- Rehabilitation of mining sites and affected landscapes, including proper disposal of chemicals and wastewater and other waste products.

Adopt policies that reduce the use of heavy rare earths in electric vehicles by fostering public transport systems and carpooling, support the reuse and recycling of rare earths and use the potential for remining of rare earths (estimated to amount to 30% of the EU’s annual consumption).

Ensure national financial systems do not facilitate money laundering related to the illicit trade in heavy rare earths.

Contact

-

Sophie Marsden

Senior Communications Advisor - Transition Minerals