BP and Shell's social media campaigns since the launch of the UK's Green Claims Code

Despite growing pressure to curb greenwashing, oil and gas majors Shell and BP continue to promote environmentally friendly narratives their core business does not back up.

In the wake of a UK government warning in late 2021 to stop making misleading environmental claims, BP has more than doubled the amount spent on purchasing advertisements that greenwash its image on Facebook and Instagram compared to 2021.

Meanwhile Shell has continued to run greenwashing ads on Instagram without disclosing the ads relate to political issues as required by the platform. Meta has allowed Shell to re-publish essentially identical political ads without labelling them as such, and continued to profit from the greenwashing ads of polluting industries.

Introduction

The fossil fuel sector has known for decades it is directly driving climate change. Instead of raising the alarm, major oil and gas companies have worked to prevent the scientific evidence from affecting their business – initially through denying or casting doubt on the evidence, then by seeking to distract attention from their harms, and delay measures to move away from fossil fuels.

One of their methods is greenwashing: marketing that gives the impression the companies are acting for the good of the climate, while their overall business remains linked to dangerous levels of greenhouse gas emissions (see box below). But this year conditions in the UK are different.

In September 2021, the Competition and

Markets Authority (CMA) – the UK’s regulator for competition and

consumer protection – launched the Green Claims Code.

The Code helps businesses understand how to communicate environmental

credentials without misleading consumers. Its launch ‘[put] businesses

on notice’ for greenwashing, giving them until the start of 2022 to

align with consumer law, before beginning a review of misleading green

claims and taking appropriate action.

One year later, we have analysed Shell and BP’s ads on Facebook and Instagram in the UK and their Twitter image posts to assess whether the companies have followed the Green Claims Code. Our analysis builds on previous research documenting fossil fuel greenwashing on social media and shows how BP and Shell have kept up their greenwashing ads despite the regulator’s intervention. We lay out a summary of our key findings below, and present the evidence behind each finding in the following sections.

The vast majority of BP and Shell’s business is in fossil fuels

Contradicting the upbeat messaging of their ads are the stark truths of BP and Shell’s environmental track records and projections. Over the course of their history, these two companies alone have produced more than 137 billion barrels of oil and gas. The scale of their production since 1965, considered the point when industry leaders knew the environmental impact of fossil fuels, puts them among the top 20 fossil fuel companies collectively responsible for more than one third of global greenhouse gas emissions in this period.

BP and Shell rank at number 6 and number 7 on the list of most polluting fossil fuel companies. Their businesses continue to be dominated by fossil fuels, and their plans for further exploitation projects are incompatible with the measures the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) requires to mitigate global temperature rises.

In the first half of 2022, BP spent about £3.1 billion on new oil and gas projects, more than 10 times what it spent on ‘low carbon’ energy (about £300 million), according to company reporting. The company has announced plans for a ‘low carbon future’, but these are far off the emissions reductions of 45% recommended by the IPCC to prevent the world warming beyond 1.5°C.

The company’s planned oil and gas projects also go against the recommendations of the International Energy Agency (IEA), which has said “there are no new oil and gas fields approved for development in our pathway” to net zero by 2050, echoing previous analyses by Oil Change International, Global Witness and others. In August 2022 the company’s CEO announced BP will boost investment in hydrocarbons by “about half a billion dollars.”

Shell’s 2022 plans put investment in

‘renewables and energy solutions’ at approximately £2.2 billion, about

12% of total investment. The company’s planned investment in oil and

gas exploration and production is close to three times higher at £5.9

billion, which has increased a third from £4.4 billion in 2021.

An

April 2022 analysis by Global Witness and Oil Change International

found that BP and Shell both rank among the top 20 companies for

projected fossil fuel development and exploration for the period

2022-2030.

Key findings

- Shell and BP’s digital promotions appear to breach UK Government guidance. Despite the warnings of the Competition and Markets Authority’s Green Claims Code, Shell and BP’s Meta advertisements present environmentally friendly images of the companies that risk misleading consumers. The advertisements disproportionately depict projects linked to the green transition. The majority of the companies’ image posts on their primary and UK Twitter accounts also showcase projects with positive environmental associations. These projects represent a small portion of their businesses, which remain dominated by fossil fuels that are damaging the climate.

- Shell and BP have continued to purchase greenwashing ads on Meta platforms in the UK since the Green Claims Code’s launch. In the first seven months of 2022, BP more than doubled its 2021 spending on purchasing green ads on Facebook and Instagram. In the same period, Shell continued to run ads on Instagram that greenwashed its image.

- Shell has repeatedly failed to declare its ads on Facebook and Instagram as being ‘political’, thereby likely evading Meta’s ad transparency requirements. Since November 2018 in the UK, Meta has required advertisers making political advertisements to verify their identity and source of payment. Since at least November 2019, advertisers have been required to self-declare if their ads are about social issues (as part of ‘social issues, elections or politics’). In the UK, this category includes ‘environmental politics’, capturing content on ‘climate change, renewable/sustainable energy and fossil fuels’. Ads declared or subsequently flagged as being political get archived in the library, whereas those not marked do not. The Meta Ad Library contains 29 distinct UK ads by Shell that have been flagged as being political – but not a single one of them was self-declared by Shell. Given Meta’s mixed results at detecting political ads, it is probable Shell has run more political ads than Meta has captured. In other words, Shell has likely avoided Meta’s transparency measures and therefore accountability for its paid communications.

- Meta

has failed to detect Shell’s environmental ads as being of a political

nature, even when the same ad content has previously been flagged and

removed. Not only has Shell failed to self-declare any of its UK ads

on Meta as being political, so too has Meta failed to quickly detect

Shell’s ads as being political. On at least six occasions in 2022 Shell

was able to republish identical ad content without political

declaration, despite the same ads previously being flagged and taken

down for not carrying the required disclaimer for political issues.

We invited BP, Shell, and Meta to comment on our findings, and received responses from BP and Meta. BP wrote to us that: “we stand by our Backing Britain campaign, which we ran from May to July 2022; we disagree with Global Witness’ characterisation of it.”

In the response from Meta, a Meta Spokesperson wrote that: “We require all advertisers running ads about social issues, including those about environmental topics to include a ‘paid for by’ disclaimer. Our enforcement is not perfect, but we’re always working to strengthen and improve our processes.” The response also provided background on the company’s advertising policies and noted it has ‘removed all ads that violated our SIEP policies’.Businesses should not focus claims on a minor part of what they do, if their main or core business produces significant negative effects. - The Green Claims Code

Shell and BP’s apparent breaches of UK government guidance

What does the Green Claims Code require?

The UK Competition and Markets Authority’s Green Claims Code is a set of guidance intended to help businesses to uphold their obligations under consumer protection law when making environmental claims, in order to protect consumers from misleading claims.

Environmental claims are defined as ‘claims which suggest that a product, service, process, brand or business is better for the environment’. These can be found in advertisements, marketing material, and branding, in which every aspect might be considered relevant (including the terms used, supporting evidence, and overall presentation).

The Code defines misleading environmental claims based on deceptive impressions. ‘Misleading environmental claims occur where a business makes claims about its products, services, processes, brands or its operations as a whole, or omits or hides information, to give the impression they are less harmful or more beneficial to the environment than they really are.’ Six principles set out how to avoid making misleading claims, of which the following three are of particular relevance to this study.

1. ‘Claims must be truthful and accurate’

This principle requires that what is said is not liable to mislead customers. It further prohibits businesses from using selective storytelling, even if factually correct, if this risks misleading consumers. According to the guidance, ‘claims which ignore significant negative environmental impacts in order to focus on minor benefits or small parts of a business’s activities are still at risk of misleading consumers.’ The text continues, ‘businesses should not focus claims on a minor part of what they do, if their main or core business produces significant negative effects.’

2. ‘Claims must be clear and unambiguous’

This principle requires clarity in the terms used in a claim and the meaning they convey to consumers. ‘The meaning consumers are likely to take from a claim and the environmental credentials and impacts of the product, service, process, brand or business should match.’ Businesses must ‘live up to the impression given’ if using vague or general terms (such as ‘eco’ or ‘sustainable’), suggesting action that is hard to substantiate.

Similarly, climate ambitions cannot be overrepresented: ‘Claims about a business’s environmental ambitions must also be in proportion to its actual efforts. They are less likely to be misleading when they are based on specific, shorter term and measurable commitments the business is actively working towards.’

3. ‘Claims must not omit or hide important information’

This principle is key to avoiding deceptive story-telling, even if the information presented is true. Per the guidance:

‘Claims should not just focus on the positive environmental aspects of a product, service, process, brand or business, where other aspects have a negative impact and consumers could be misled. This is especially so if the benefits claimed only relate to a relatively minor aspect of a product or service or part of a brand’s or a business’s products and activities. Cherry-picking information like this is likely to make consumers think a product, service, process, brand or business as a whole is greener than it really is.’

Selective accounts of a company’s behaviour can easily slip into greenwashing, if masking wider environmental harms.

Applying the Code

In the material included in this study from both BP and Shell, the ad campaigns signal strong environmental action that does not correspond with their wider investments and activity. By promoting agendas in these ads that consist almost exclusively of projects with positive environmental associations and largely do not account for the environmental harms of their core business, these companies are likely to mislead consumers as to their overall performance on climate.

Shell’s misleading messaging on Meta

We

counted 14 distinct ads by Shell that have run on Instagram in the UK

in the first 7 months of 2022 and have been flagged for being political

(all for environmental issues). This is about twice as many political

ads as the company ran on Facebook and Instagram in all of 2021 (7) or

2020 (8). The 2022 ads garnered over 2.2 million impressions.

All of the 2022 ads examined are short videos (13-20 seconds) that promote a company agenda of climate action, each finishing with a line of text, ‘The UK is READY for Cleaner Energy’, above the Shell logo and the hashtag ‘#PoweringProgress’. Nine of the 14 videos feature developments around electric vehicles; three focus on household energy under the caption ‘1.4 million households use 100% certified renewable electricity from Shell Energy’ (one of the three runs without a caption but contains similar text); and the remaining two videos feature a Shell wind power project that ‘could power 6 million homes’.

Yet for all the ad campaigns’ green claims, an April 2022

investigation by Global Witness and Oil Change International found that

Shell is among the top 10 highest spending companies for projected

fossil fuel development and exploration of the period 2022-2030.

Shell’s record does not reflect the environmentally friendly image its

ad campaigns suggest: its investment in cleaner energy has totalled

about £2.3 billion since 2016, against about £61 billion on oil and gas

exploration and development.

One of Shell’s Instagram ads from June 2022. Meta Ad Library

For 2022, Shell’s planned investment in ‘renewables and energy solutions’ stands at about 12% of total investment. The company has said its marketing division captures additional ‘low-carbon businesses’ including ‘EV charging and low-carbon fuels, and a joint venture in Brazil that is a world-leading bioethanol producer’.

Shell has also said that 35% of capital expenditure in 2022 would go towards low-carbon energy, as well as “non-energy products”, and that it will invest £20-£25bn in UK energy in the next decade, with more than 75% going towards low-carbon energy. Yet the company still will not specify how much it is investing purely in renewable energy sources, raising concern that its ‘low carbon’ category enables the continued use of fossil fuels.

Moreover, Shell has said “the world will still need oil and gas for many years to come. Investment in them will ensure we can supply the energy people will still have to rely on, while lower-carbon alternatives are scaled up.” But as already noted, the IEA has said “there are no new oil and gas fields approved for development in our pathway” to net zero by 2050, a finding echoed by Oil Change International and others. Meanwhile, Shell’s planned emissions from 2018 to 2030 are estimated to make up close to 1.6% of the global 1.5°C carbon budget.

Independent assessments of Shell’s climate action also present critical reports on the company. Oil Change International finds that Shell’s “climate pledges and plans are grossly insufficient.” It notes the company continues to approve new extraction projects and does not meet the rate of decline in fossil fuels necessary to align with 1.5°C. The Climate Action 100+ Net Zero Company Benchmark finds that Shell fails to meet all criteria for interim GHG reduction targets, decarbonisation strategy, or the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures.

Further, the company fails to meet any criteria for capital alignment – the important task of decarbonising capital expenditures. Rather than actually cutting its emissions, Shell’s transition plan relies heavily on Carbon Capture and Storage, an unproven technology, and questionable “nature-based solutions” such as reforestation.

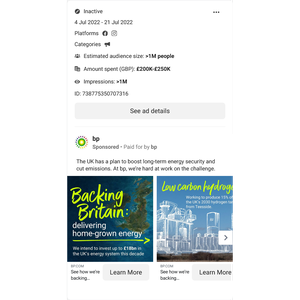

BP’s misleading messaging on Meta

We counted 15 distinct ads by BP that have run on Facebook and Instagram in the UK in the first 7 months of 2022 carrying a disclaimer for being political (all for environmental issues), with a total spend to Facebook and Instagram of about £840,000. This is more than double the amount the company spent on political ads in 2021 (about £370,000), and a still more dramatic increase from 2020 (where there are no ads listed in the library) and 2019 (about £6,500). The ads feature themes including emissions cuts, electric vehicles, renewable energy, and net zero.

BP’s ads on Meta form part of a larger advertising campaign centred on British energy production, using the taglines ‘home-grown energy’ and ‘backing Britain’. A mixture of carousel banners and short, animated videos showing different energy projects and green undertakings, the ads employ cheerful, green script and illustrations evocative of architectural renderings to suggest that the company is committed to developing the UK’s green transition.

Example of BP’s carousel ad, July 2022. Meta Ad Library

The title language used in most of the ads suggests the company shares the collective priorities of the country: ‘The UK has a plan to boost long-term energy security and cut emissions. At bp, we’re all in.’ Several use an aerial image of the UK looking green, overlaid with an up-beat message in a font that resembles hand-writing: ‘Home-grown energy: £18 billion of it -> We intend to invest up to £18bn in the UK's energy system by 2030.’

The company includes the claim in its social media ads that it intends to invest ‘up to £18 billion’ in the UK’s energy system by 2030 and has said elsewhere that about three-quarters of this will be in ‘low carbon’ energy. However, in the first six months of 2022 it spent only about £300 million globally on its ‘low carbon’ business – which does not just cover renewables, but can include more speculative, non-renewable technologies (neither BP nor Shell publishes figures specifically for renewables investment).

Given BP’s profits for 2021 reached about £9.5 billion, and hit approximately £12 billion for the first half of 2022, the company’s investment does not resemble an ambitious agenda in the face of the climate crisis. Nevertheless, BP has spent over £800,000 on Meta advertisements in the UK alone to promote the message it is ‘all in’ on the UK’s plan to ‘boost long-term energy security and cut emissions’.

The same campaign continues with a carousel ad containing four slides showcasing BP’s investments in the UK’s energy system. Three of the four slides feature projects evoking greener energy: ‘Low carbon hydrogen’; ‘Offshore wind’; and ‘EV charging’. One slide of the four features fossil fuels: ‘North sea oil & gas’.

BP’s qualifier

BP has faced criticism and a legal complaint by Client Earth for misleading ad campaigns and in some of its 2022 ads (including the carousel ad referenced above) includes a caveat. This reads ‘Today, most of the energy we produce is oil and gas. But as we transition towards net zero that will change. This decade we plan to increase to 50% our capital expenditure on our transition businesses globally, and reduce oil and gas production by around 40%.’

BP’s qualifier slide. Meta Ad Library

This qualifier is not up to task. It suggests the company’s ambition is to reduce oil and gas production to achieve net zero emissions. Yet as Oil Change International has shown, BP has not set any end date for its oil and gas production, and instead uses net zero targets that depend on unproven Carbon Capture and Storage technology.

It further notes the company also ‘continues to frame fossil gas production as low carbon, even listing a “shift to gas” as a key action it is taking toward its misleading “net zero” intensity target for energy products sold.’ BP’s continued fossil fuel exploration in countries where it operates goes against the findings of the International Energy Agency, which does not approve any new oil and gas fields for development in its pathway to net zero.

Other independent analyses find further fault with the claims presented by BP on its net zero agenda. In the Climate Action 100+ Net Zero Company Benchmark, BP does not meet all the assessment’s criteria for setting ‘an ambition to achieve net zero GHG emissions by 2050 or sooner’. The company misses the criteria to cover ‘the most relevant Scope 3 GHG emissions categories for the company’s sector’. Scope 3 refers to the indirect emissions taking place in a company’s value chain – for example the emissions from oil and gas once it has been used by consumers.

Without a commitment to account for its

Scope 3 emissions, it is difficult to take a company’s climate ambitions

seriously, particularly for oil and gas companies (Scope 3 emissions

account for about 85% of the industry's emissions, according to Carbon

Tracker.) The Climate Action 100+ assessment also finds that BP does not

meet all of its criteria for other GHG reduction targets,

decarbonisation strategy, climate policy and engagement, among others.

Twitter images suggest greener activity

BP and Shell’s image posts on Twitter also disproportionately present greener narratives of the companies’ activity. Among their organic content, a review of BP and Shell’s tweets containing images (including the image and any text) from the first seven months of 2022 showed that the majority depict scenes of renewable energy projects or electric vehicle infrastructure.

We believe that the two companies are therefore giving an impression of environmental action in the majority of their recent image tweets, despite the CMA’s warning against cherry-picking material that can mislead the public about a business’s environmental impact.

Of the nineteen images Shell tweeted from its primary account (@Shell), eighteen had green themes. These featured wind power heavily, along with electric vehicle infrastructure, and a venture purporting to help decarbonise air travel using blockchain. The only image not to have a green association was a graphic of a statement by the company about the war in Ukraine.

All fifteen of the images tweeted from the company’s UK

account (@Shell_UKLtd) over the same period had green themes, primarily

promoting electric vehicle charging stations and wind power. Yet again,

the company’s social media promotion projects an environmentally

friendly agenda that is not lived up to by its far larger investment in

fossil fuels - which unsurprisingly does not feature in these images.

On the BP United Kingdom (@bp_UK) account, eight of twelve tweeted images contained scenes with green associations. These included electric vehicle charging hubs, wind turbines and wind power conferences. The others promoted a responsible business initiative, presented a view of Teesside with a link that opens a page on BP’s hydrogen plans, and commemorated the Queen’s Jubilee.

Dangerous promotion

BP and Shell’s ads on Facebook and Instagram and their tweets containing images on Twitter suggest that these fossil fuel giants are committed and working towards clean energy futures. They project a confident tone about the company’s steps to help address a collective challenge. This is concerning as it presents a false sense of security to audiences about the actions of these major polluters.

The takeaway from the advertisements is that the companies are part of the solution to climate change, but this is not borne out in the vast amounts of continuing and planned fossil fuel exploitation the companies are conducting but omitting from their social media promotion. Previous studies have shown that these fossil fuel projects are set to push global temperatures above the 1.5°C commitment of the Paris Agreement. The scale of these projects makes the companies’ stated investments in renewable energy risible by comparison.

The advertising campaigns examined here also fall into a pattern of distraction and delay. Rather than confronting their significant contribution to global heating – through the release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere from the extraction, transport, and combustion of fossil fuels – the companies have purchased ads that promote their initiatives that appear environmentally friendly. Yet the messaging avoids how the companies are causing far more emissions than they are reducing. The ads distract from the companies’ continued business in oil and gas (which features little or not at all) and its centrality to climate change.

Similarly, an investigation by Eco-Bot.Net and The

Guardian calls out the timing of the ads for occurring around political

debate on energy taxes. It found the ads ‘began two days after Labour

proposed a windfall tax on North Sea oil and gas in January. BP’s

spending on these ads escalated in the weeks before Rishi Sunak

announced an “energy profits levy” on 26 May.’ The distraction from

harms serves to delay having to move away from business models that are

highly profitable, yet require urgent changes to avoid increasing global

temperatures beyond 1.5°C.

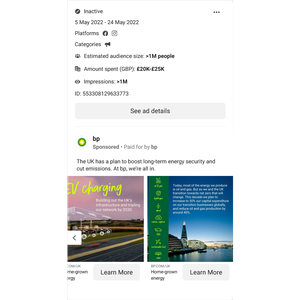

Slipping through the cracks: Shell’s undeclared messaging

Shell has repeatedly failed to declare its ads on Facebook and Instagram as being political, thereby likely evading Meta’s ad transparency requirements.

Since October 2019, Shell has run at least 29 distinct political (environment issue) ads on Meta’s platforms in the UK. Not one of these was launched with the disclaimer required by Meta for ads about social issues, elections or politics. The 29 ads we have data on were later marked by Meta as containing political content and removed from the platform for violating their rules. As a result of being detected as being political ads, Meta has archived them in the ad library.

A Shell ad re-launched on different dates despite being flagged for running without a disclaimer. Meta Ad Library

Shell’s ads raise concerns about the company’s advertising strategy on the platform, as it has consistently run environmental ads in the UK without declaring their political content. The library data suggests the company can get away with it: about 80% of the archived ads from the first seven months of 2022 ran for more than 3 days (on average 14 days; some for as long as 37 days) before being taken down. Several were subsequently relaunched, again without a disclaimer, to run for further lengths of time.

For example, in June 2022 Shell launched a 16-second video with the title text, ‘In the UK, 1.4 million households use 100% certified renewable electricity from Shell Energy.’ This initially ran from June 16 to June 22, when it was presumably flagged for not carrying a disclaimer and removed. The very same video appeared a further two times, running for 12 and 37 days, in each case without the disclaimer for political issues.

As Meta does not archive old ads which have not been declared as being of a political nature and has known imprecision with detecting political ads, it is probable Shell has run more political ads than the library has captured. In other words, Shell has likely avoided Meta’s transparency measures and therefore accountability for its paid communications.

Meta’s platform problems

Meta has failed to detect Shell’s environmental ads as being of a political nature, even when the same ad content has previously been flagged and removed.

While polluting industries are responsible for their emissions and environmental claims, other actors facilitate greenwashing by helping craft and disseminate their public communications. The ads in this study all ran on Facebook and Instagram – platforms that are therefore enabling and profiting from BP and Shell’s misleading messaging. While Meta’s provision of the Ad Library and ad labels are important steps towards greater transparency, their omissions prevent meaningful accountability.

This study found that Meta repeatedly failed to

detect ads by Shell containing environmental messaging covered by the

platform’s UK issue category of ‘environmental politics’ that should

have been launched with the required disclaimer. The platform later

removed Shell ads that had been flagged or reviewed, then in three cases

allowed the same videos to run as new ads when reposted after a period

of days. The process repeated a second time, illustrating major

shortcomings in Meta’s political ad detection system.

Recent research offers wider evidence of imprecision or failings in the ad detection system. An academic study found the platform misses close to 60% more ads than it detects worldwide, and that detection performance is uneven across countries. Global Witness has found the company’s advertising system has failed to detect hate speech and disinformation in various countries; and moreover, that its algorithms tend to drive climate-sceptic users toward extreme climate denial content.

By failing to detect political or banned content, the platform does a disservice to users. Advertisers like Shell and Chevron have been able to repeatedly run political ads without declaring them. They appear to do so without repercussion as they have been allowed to republish political ads despite not abiding by Meta’s ad policy. Meta’s policy does allow for further enforcement actions such as restricting ad accounts, which appear not to have been taken.

Facebook says it prohibits misleading claims on its site, but continues to allow fossil fuel companies to greenwash their image through ads. Regardless of label requirements, Meta and other advertising platforms should not be profiting from the promotion of polluting industries.

The fossil fuel industry’s insidious record of greenwashing

Shell and BP are not the only companies promoting an alternative account of their environmental record. A 2021 study found that close to two thirds of social media posts by six major European fossil fuel and energy companies between December 2019 and April 2021 are greenwashing.

Shell

is also no stranger to regulatory action over misleading environmental

claims. In September 2021, the Netherlands’ advertising watchdog ruled

that the company’s claim of carbon neutral driving is greenwashing. The

watchdog again ruled in June 2022 that a Shell ad campaign about its

efforts to reduce carbon dioxide emissions is misleading and must be

ceased.

The public mood is hardening against advertisements

for commodities that negatively impact the environment. In an April 2022

poll on attitudes to advertising more than two thirds of UK adults said

they wanted curbs on advertising for products that are harmful to the

planet.

Conclusions and recommendations

One year on from the UK Competition and Markets Authority’s warning to clean up misleading environmental claims, fossil fuel majors BP and Shell have continued to put out greenwashing material in the UK on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. The 2022 advertising campaigns of Shell and BP on Facebook and Instagram in the UK and their images posted on Twitter offer a rosy picture of their climate action. They present narratives of the companies’ commitment to a green agenda, depicting plans for the construction of electric vehicle infrastructure, wind farms, and low carbon projects.

While the two companies are investing in these areas, the scale and proportion of investment are dwarfed by ongoing and planned spending on fossil fuel exploitation, at levels that are not compliant with the Paris Agreement. Crucially, the companies’ overall business activity remains markedly different to the green image they are promoting – despite the CMA’s guidance against selective storytelling, omission of information, and inaccurate impressions of environmental impact.

Rather than investing in our future, as their messaging suggests, these companies continue to drive fossil fuel use that heralds a future of deadly heat, mass displacement, and the devastation of natural life. In May 2022, Oil Change International assessed the companies’ climate plans with respect to ambition and integrity and found that both Shell and BP were ‘grossly insufficient’. Shell’s plan was criticised for 2030 targets that do not align with the Paris Agreement, risky and potentially misleading metrics, and heavy reliance on offsets rather than emissions cuts.

BP’s plan is criticised

for allowing new exploration in the more than 60 countries where it

already operates, framing fossil gas production as low carbon, and for

reliance on speculative Carbon Capture and Storage to meet emissions

targets. These assessments paint a dire picture of the companies’

overall climate action, and call into question their advertised stances

as aiding the green transition.

With time running out to limit

the rise in global temperatures, the oil and gas and other highly

polluting industries must urgently make drastic emissions cuts if we are

to avert climate catastrophe. Greenwashing their public reputations in

their digital advertisements is a dangerous diversion from the impact of

these companies’ activities on the climate, and engenders a false

optimism about the changes they are making to their business models.

We call on the UK government to:

- Investigate the green claims of BP, Shell, and other fossil fuel companies under consumer law and take appropriate action.

- Strengthen the powers of the CMA and other regulators to hold companies to account for greenwashing, including through fines for breaching consumer law or promises to regulators.

- Accelerate a low carbon future through comprehensive investment in renewable energy, low carbon infrastructure, insulation and energy efficiency.

We call on Shell, BP, and other oil and gas companies to:

- Stop greenwashing their business activities. Companies should be transparent about their advertising activity and spending.

- Prioritise rapid decarbonisation and investment in renewable energy.

We call on social media and advertising platforms including Facebook and Instagram to:

- Stop publishing ads from polluting industries.

- Improve detection of prohibited content.

- Archive all ads in a publicly available library, not just ones that advertisers self-declare or Meta detects as being about social issues.

- Identify and suspend repeat violators of their advertising rules from advertising on their sites.

- Download a PDF version of this aticle : Fossil fuel greenwash (813.6 KB), pdf

Methodology

We reviewed all political advertisements shown to users of Facebook and Instagram in the UK from BP’s primary account and Shell’s primary account that are listed in Meta’s Ad Library. Our findings reflect search results for the period ending July 31 2022, as listed on the Ad Library in August 2022. We also reviewed the tweets containing images (and any coupled text) from the primary and UK accounts for Shell (https://twitter.com/Shell and https://twitter.com/Shell_UKLtd) and BP (https://twitter.com/bp_plc and https://twitter.com/bp_UK) from January 1 2022 to July 31 2022.

The

Meta Ad Library contains currently active ads and previous ads

categorised as being about social issues, elections or politics across

Meta’s various platforms. It was first introduced in May 2018 amid

heightened controversy around Facebook’s data practices and impact on

elections following the Cambridge Analytica scandal. British ads by BP

and Shell about the environment should be categorised as being about

social issues, elections or politics, and therefore archived in the Ad

Library because among the political issues Meta categorises in the UK is

‘environmental politics’, capturing content on ‘climate change,

renewable/sustainable energy and fossil fuels’.

The

advertisements were recorded along with the amount spent on their

promotion, the number of ads launched, and the number of ad impressions.

Data for ad spending and impressions were usually listed with upper and

lower ranges, from which we calculated the midpoints for ease of

comparison. Some currency values in the report have been converted from

USD to GBP for consistency, using the exchange rate at time of data

publication, and rounded to two significant figures where applicable.

The Meta Ad Library presents the contents – the ‘creative’ or ‘creative object’ – of each ad and various data about its publication and reach. If the creative object has been used simultaneously with slightly different distribution targets, for example, the library may indicate that a (listed) number of ads that ‘use this creative and text’. We treated each such instance (where, for example, ‘6 ads use this creative and text’) as counting as one distinct ad.

These are not what might be

termed unique ads, which could suggest a creative object is only counted

once as an ad on its first appearance. Instead, the tally of distinct

ads captures every ad box listed in the library’s search results as one

ad, including when a creative object has been republished for a second

or third time. The advertising formats included videos, animations,

images with text, and short clips displayed on media carousels.

To

examine the companies’ Twitter images, we worked with researchers from

the Department of Digital Humanities at Kings College London and the

Public Data Lab to collate images tweeted by the companies. This enabled

us to review image and content over time, including coupled text.

![VCMIsimple4[60].png](https://cdn2.globalwitness.org/media/images/VCMIsimple460.2e16d0ba.fill-544x300.png)