- Receipts obtained by Global Witness show Cargill is systematically failing to collect key data about the origins of its soy supplies in Bolivia, without which it cannot confirm purchases are deforestation-free. These findings cast serious doubt on Cargill’s public commitments to achieving fully traceable and “deforestation-free” supply-chains in the near future.

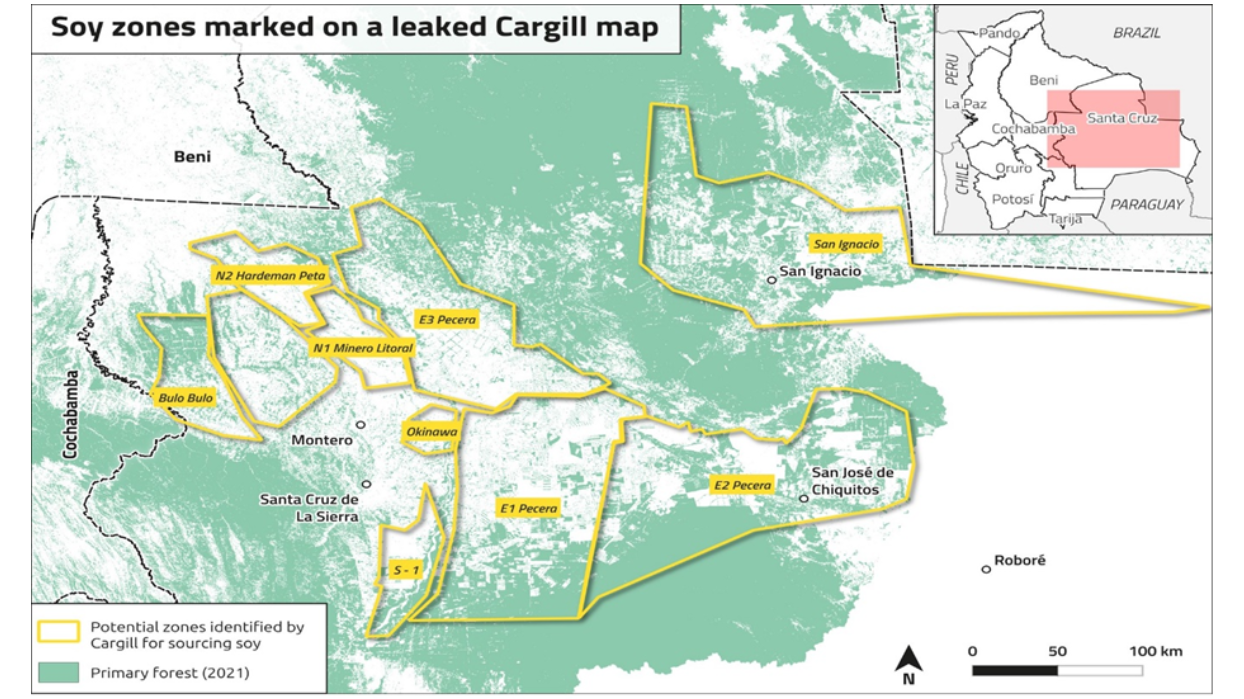

- Cargill appears to be open to sourcing future soy supplies from areas that would put more than three million hectares of standing forest at risk, according to analysis of a company map leaked to Global Witness.

- Cargill’s global operations have been bankrolled by billions of dollars from financial institutions including Barclays, BNP Paribas, HSBC and Santander, despite pledges by these financial firms to eliminate or reduce deforestation from their portfolios.

- New due diligence regulations are required in global finance centers like the UK, US and EU to stop finance flowing to companies unwilling or unable to prevent deforestation through their purchases and supply chains.

This report concludes with a series of urgent recommendations to the EU and UK, US and Bolivian governments, to the world’s biggest and most influential banks, and to Cargill itself.

A sign pointing the way to a silo used to store soy near San José de Chiquitos in Santa Cruz.

Big forests, big problems

Bolivia has the ninth largest forests in the tropics, but one of the very worst rates of deforestation. In 2022, for the third year running, the only two other countries that lost more primary forest were Brazil and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, according to Global Forest Watch.

Easily the most impacted region is Santa Cruz, in the east of the country. Over the last 20 years an estimated 83% of all Bolivian deforestation has occurred in that region, and the expansion of mechanized agriculture, mainly for soy and cattle, is reported to be the main driver.

Soy is Bolivia’s top crop, with almost 1.5 million hectares under cultivation. Approximately two thirds of that soy is destined for export, and more than half is likely to come from illegally cleared land. It is estimated that at least 74% of Bolivia’s deforestation for agriculture is likely illegal.

Bolivia’s soy production has boomed in recent decades, but the production of staple foods has dropped. Bolivia’s intensive agriculture depends on imported agricultural inputs such as pesticides, fertilisers, genetically-modified seeds and machinery. Agribusiness-driven deforestation has had devastating social and environmental impacts, including wildlife habitat destruction and the invasion of indigenous territories.

A soy field near San José de Chiquitos in Santa Cruz.

Enter Cargill

Cargill is the biggest private company in the US, with a revenue of US$177 billion in 2023. Owned mostly by members of the Cargill-MacMillan family, 14 of whom were reported by Forbes to be billionaires, it is the biggest agribusiness in the world by revenue. The company’s grip on the global food supply is hard to overstate.

Cargill says it has operated in Bolivia since 1987, and the company was the single biggest buyer of Bolivian soy in 2018, according to analysis of trade data by Global Canopy’s “Trase” initiative. In 2019 and 2020 it was the second biggest buyer, with only Peruvian company Alicorp, through two subsidiaries, handling more. According to Cargill, it exports Bolivian soy to “markets all around the world” with the prime destinations all in South America: Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Uruguay and Chile.

“The last great tropical dry forest in the world”

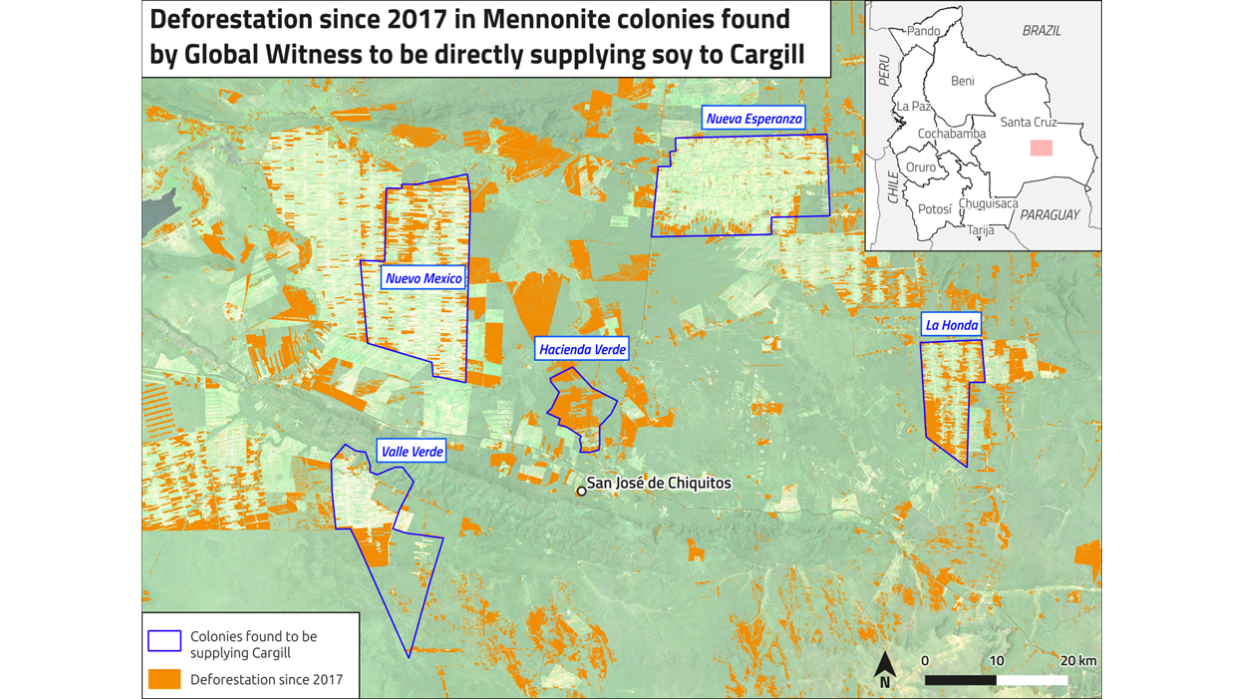

Global Witness identified dozens of areas in Santa Cruz deforested and planted with soy since 2017. We spoke with farmers and supply-chain actors to uncover who has been buying this soy. The forest in the region we visited is known as the Chiquitano, considered to be globally “unique” and “the last great tropical dry forest in the world”, as well as an ecological “transition zone” between the tropical Amazon and dry Chaco forests.

1000s of hectares of forest were cleared in the Mennonite colony of Nuevo Mexico between 2017 and 2022.

The Chiquitano stretches for millions of hectares across Santa Cruz and over the border into Brazil and Paraguay. Although comparatively little studied, it contains “extraordinary natural riches” including more than 1,200 mammal, bird, amphibian and reptile species, some of which are endemic.

In recent years the Chiquitano has become a deforestation hotspot. Soy and cattle-ranching are the main drivers, but out of control fires are also a factor – mostly used as part of deliberate efforts to clear the forest for agriculture.

In 2019 Bolivia was rocked by one of the biggest environmental catastrophes in its history when millions of hectares were impacted by fires, with the Chiquitano the worst impacted.

The significance of South America’s tropical dry forests and Bolivia’s Chiquitano in particular was acknowledged recently by the International Union for Conservation of Nature when it declared them a conservation priority, calling the Chiquitano one of only a few tropical dry forests still boasting “large sectors” but saying that “deforestation rates are increasing and alarming.”

What we discovered

Cargill can be linked to many of the areas identified by Global Witness either directly through its subsidiary Cargill Bolivia, or indirectly through other companies from which other Cargill entities buy soy. Most of the areas visited by our researchers were “colonies” - “colonias” in Bolivian Spanish – owned and farmed by Anabaptist Christian communities called Mennonites, who farm areas sometimes extending for tens of thousands of hectares.

The links between Cargill and these colonies can be proven by receipts bearing the US company’s name that were shown to Global Witness by Mennonites living there and known as “distributors” (“distribuidores”). These small-scale soy industry middlemen work with the farmers, with the seed, pesticide and fertiliser companies, and with the intermediary companies brokering sales to the processing mills and/or exporters and traders like Cargill.

Sources: Natural Earth, Sentinel-2 cloudless - https://s2maps.eu by EOX

IT Services GmbH (Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data 2021);

Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA, accessed through Global Forest Watch; Yann le

Polain de Waroux (2020), https://doi.org/10.5683/SP2/I4FEQZ

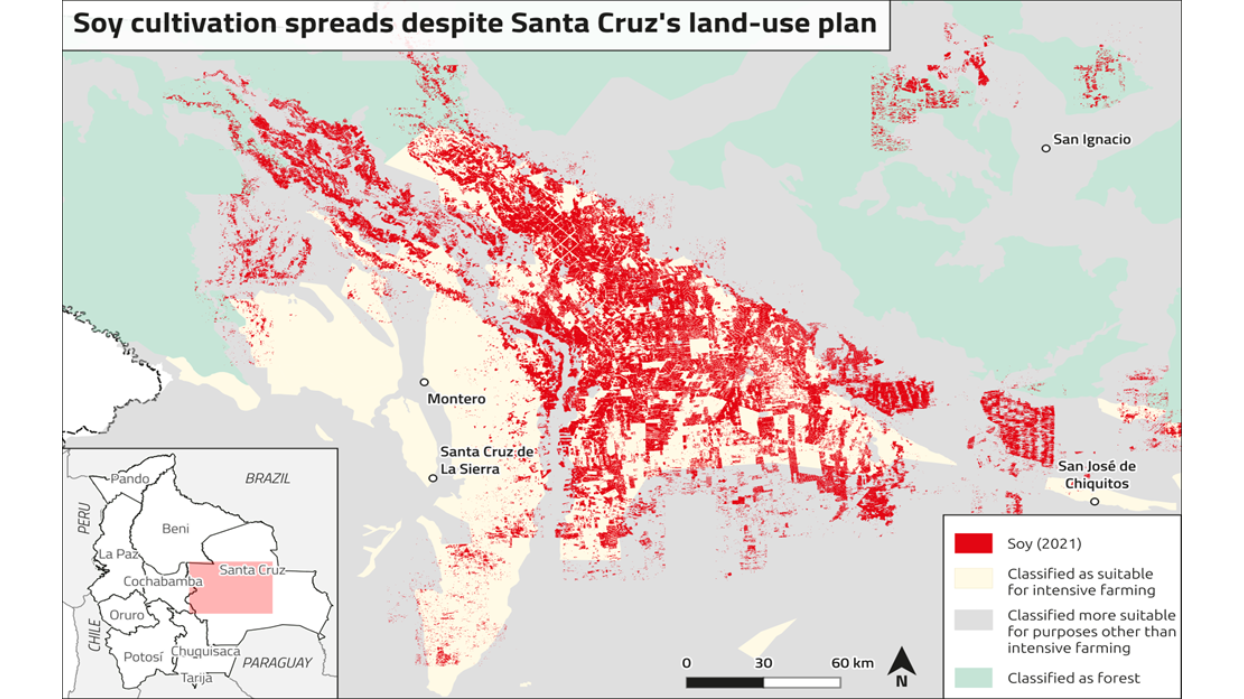

These receipts were issued by Cargill’s silos or other storage facilities linked to the company after the soy has been transported there from the point of harvest. Below is an example of one of the receipts seen and photographed by Global Witness in the five colonies. Table 1 summarises our analysis of these receipts. Most of these areas, according to our analysis, have been deemed more suitable for purposes other than intensive farming by a legally-binding regional government’s land-use plan, known as a “Plan de Uso de Suelo” (PLUS).

Cargill confirmed it does business with all five communities identified by Global Witness. It told us: “We constantly monitor our suppliers and can confirm that the Mennonite communities in question are in compliance with our Police on Sustainable Soy [sic].”

The company said it investigates all allegations received and blocks suppliers if policies and commitments are found to have been violated. The company said it has mapped 26 polygons - a type of farm boundary - across the five Mennonite colonies named by Global Witness and based “on this mapping available and on the mass balance methodology, we can infer that the products received from at least four from the five colonies could be produced in the hectares opened before 2017. Just on the case of one of those communities we cannot assure that the grains were produced on lands deforested before 2017. Which does not necessarily mean that this is non-compliant with the local legislation or Cargill commitments.” Cargill says it works with the Bolivian Soy Roundtable to establish “minimum socio environmental criteria for soy origination in the country”.

Big money

Complicit in Cargill’s Bolivia operations are global banks such as Barclays, BNP Paribas, HSBC and Santander, who have provided financial services to the company worth billions of dollars since 2021 according to the Forests and Finance database. For example, last year Cargill issued bonds worth over US$2 billion which were underwritten by BNP Paribas, Barclays, Santander and Bank of America, among others. In 2021 a consortium including Bank of New York Mellon, BNP Paribas, Deutsche Bank and HSBC arranged a US$6 billion revolving credit facility for Cargill, while that same year Deutsche Bank was also part of a syndicate that provided a US$1.3 billion corporate loan to the company.

These deals were made despite an increasing number of financial institutions apparently becoming more interested in reducing or ending their portfolios’ exposure to deforestation. One example is BNP Paribas. In 2021 it pledged “not to finance customers producing or buying beef or soybeans from land cleared or converted after 2008 in the Amazon”, and by 2025 to require “full traceability of beef and soy (direct and indirect) channels” for all its customers. BNP Paribas told Global Witness it uses this policy and other systems to “identify, assess and manage the environmental and social risks and impacts of the activities of our clients”, noting “we value the information you provided regarding Bolivia as it will inform the discussions we have with our client.”

Such deals were also made despite countless exposés of Cargill’s links to deforestation over the years, going back at least as far as 2016. Greenpeace’s 2006 report Eating up the Amazon identified the company as one of “three U.S.-based agricultural commodities giants at the heart of the Amazon destruction.” There is no way these banks could convincingly claim they were not aware of the deforestation risks when they decided to service Cargill.

Deutsche Bank rejected “accusations that we are knowingly providing direct financing for projects or activities related to deforestation of primary tropical forests or that are located in sensitive areas such as “high conservation value” areas” and expected its clients to “publicly demonstrate their commitment to No Deforestation standards”. Barclays, Bank of America and BNY Mellon declined to comment. HSBC did not respond. Santander said it could not comment on client relationships but “operates strict policies that govern our financing”.

Is Cargill deliberately failing to record the origin of its soy?

These receipts obtained

by Global Witness not only link Cargill to soy from Mennonite colony properties

where forest has recently been cleared, but they also show that the company is

failing to record or request exactly where the soy has been grown when it is

deposited at the silos and other storage facilities it owns or rents. This

information is needed by Cargill to reach its traceability goals and check if the

purchased soy is deforestation-free. If it wasn’t for these receipts being

shown to us, it would probably be impossible to connect that soy to the

company.

“Cargill doesn’t necessarily know it’s coming from this colony,” one anonymous source told Global Witness. “It doesn’t matter [to them]. Where it comes from doesn’t matter. All that they care about is that you close the price on the soybeans and they get delivered.”

Receipts seen by Global Witness suggest other companies in Bolivia make more of an effort to track the origins of the soy arriving at their silos. For example, receipts seen by Global Witness issued by Gravetal – another food company in Bolivia – include space for “procedencia” (“origin”), “proveedor” (“supplier”) and “agricultor” (“farmer”).

A receipt issued by the company Gravetal after soy was delivered to its installations on the border with Brazil. Unlike the Cargill receipts seen by Global Witness, this Gravetal receipt includes space for the name of the individual farmer who cultivated the soy.

Those issued by Cargill’s Tres Cruces silo only ask for “procedencia” and “remitente” (“sender”). On every one of the Tres Cruces receipts seen by Global Witness it simply says “Santa Cruz” for “procedencia”, which is so vague as to be meaningless for traceability purposes.

Future plans?

In addition to buying soy from properties where forest has been recently razed, Cargill also appears open to sourcing soy from huge areas across Santa Cruz with currently standing forest. That is suggested by a leaked company map, showing numerous zones marked in yellow, reportedly dating from 2018, which has been obtained by Global Witness.

Below is our own version of that map, with the zone furthest to the east, beyond Roboré, omitted:

Sources: MapBiomas Amazonia Project – Collection 4 of the annual series of land use and land cover maps of the Amazon, acquired on 11/6/23 from https://amazonia.mapbiomas.org/mapas-de-la-coleccion; Natural Earth; HDX

If all the zones marked on the map above were planted with soy, more than three million hectares of forest would have to be cleared, according to Global Witness estimates. In addition, the zone beyond Roboré, far to the east of Santa Cruz’s capital, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, represents a dramatic expansion of the “agricultural frontier.”

Moreover, a significant proportion of the zones

identified by Cargill are in parts of Santa Cruz deemed more suitable for

purposes other than intensive farming by the regional government’s

land-use plan. According to our analysis of that plan, only a small percentage

of Santa Cruz should be intensively farmed. As our map of the west and centre

of the region below shows, there are currently huge areas where soy is being

grown that the regional government has deemed more appropriate for purposes

other than large-scale crop cultivation:

Sources: Santa Cruz department government, Global Land Analysis & Discovery (GLAD); Natural Earth, HDX.

Cargill did not respond to Global Witness’s questions about the map or its sourcing practices from areas deemed suitable for purposes other than “intensive farming”.

Empty promises

The findings in this report call into question Cargill’s claims about sustainability, traceability, its operations in Bolivia, and its commitments to ending deforestation in its supply-chains worldwide. In 2014, it signed the New York Declaration on Forests agreeing to eliminate “deforestation from the production of agricultural commodities such as palm oil, soy, paper and beef products by no later than 2020.” The company subsequently abandoned that goal and postponed its target to 2030.

However, at the United Nations climate change COP27 conference last year, Cargill, along with 13 other companies, launched a “roadmap” establishing a 2025 target date for the removal of deforestation for soy production in the Amazon, Cerrado and Chaco. That “roadmap” has been fiercely criticised by civil society and a group of Cargill’s largest customers, including McDonald’s, Nestlé, Unilever and Walmart. Bolivia’s Chiquitano is not included as a distinct area in the roadmap and therefore does not appear to be covered by the 2025 target. By the end of 2023, the traders are obliged to conduct a global risk assessment to identify other relevant biomes and “develop additional implementation plans and targets as needed", which Global Witness recommends should include the Chiquitano.

Regarding Bolivia in particular, Cargill says it aims to have “the most sustainable food industry supply chains in the world” while a 2021 sustainability report claims traceability in Bolivia is fundamental to its business and that it is committed to “[T]ransforming our supply chain to be deforestation-free, protecting forests and native vegetation.” That report also claims it is “making good progress in mapping our network of soy suppliers” in Bolivia, having moved “from mapping with geo-referenced points to the more sophisticated methodology of polygon mapping of all our direct suppliers’ field boundaries.” It adds that it “is aiming to identify the origins of all our soybeans” across South America as a whole.

However, our findings suggest that Cargill cares little about deforestation or protecting forests in Bolivia, and that it is more committed to what might be called “supply-chain untraceability”. It appears that the company is not even trying to identify the origins of its Bolivian soy, let alone succeeding. Any claims of making “good progress” seem deceptive.

Don’t “Mother Earth’s” forests need protecting?

Deforestation in Bolivia has been driven by numerous factors including a global soy boom and the willingness of companies like Cargill to operate irrespective of the environmental destruction involved. But Bolivian government policy promoting large-scale agriculture has played a fundamental role too. Key decisions include permitting the cultivation of the genetically modified soybean variety known commercially as “Roundup Ready”, the 2013 adoption and implementation of the “Patriotic Agenda 2025” and the “Economic and Social Development Plan 2016-2020”.

The Bolivian government – which did not sign

the Glasgow Leader’s Declaration on Forests and Land Use at COP26 in 2021 - has

also unleashed a program of environmental deregulation intended to facilitate

large-scale agricultural expansion. This has included laws and other

administrative measures making it easier for smallholders and communally-owned

properties to deforest up to 20 hectares, reducing or abolishing fines for

people who illegally clear forest, and pardoning others who have done so in the

past, among other things.

All this has been happening despite Bolivia’s stated commitment to defend “Mother Earth”, including its 2009 Constitution acknowledging the importance of protecting nature and two laws in 2010 and 2012 purportedly enshrining the rights of “Mother Earth” herself. The 2010 law made Bolivia the first country in the world to grant statutory rights to nature. This was no small achievement, but these laws did not prevent record-high levels of tropical forest loss in Bolivia in 2022.

Recommendations

In light of our findings, the EU, UK, US and other governments should:

- Legislate to introduce mandatory environmental and human rights due diligence for the financial sector to prevent lending and investment in companies with insufficient deforestation controls, accompanied by effective monitoring and enforcement mechanisms and a civil and criminal penalty regime.

- More specifically, introduce rigorous and detailed environmental due diligence standards to accompany this legislation requiring banks and other financial institutions to identify, report, mitigate and prevent the risk of deforestation and associated activities such as land grabs and human rights abuses.

- Ensure legislation and policies aiming to prevent the import of forest risk commodities produced on deforested land – such as Schedule 17 of the UK’s Environment Act 2021 – include soy and any soy-derived products.

- Ensure that trade negotiations, development finance or other policies targeting Bolivia do not increase the pressure on the country’s forests by promoting agricultural expansion and other economic activities at a high risk of increasing soy-related deforestation and conversion.

- Ensure measurable and dated zero-deforestation targets are included in all green finance and real economy regulations, such as mandatory net zero transition plan templates and corporate climate disclosure and reporting frameworks.

- Ensure all financial regulation and supervision is aligned with the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use pledge to “re-align” the financial system with forest protection, and the binding target to limit climate change to 1.5c under the Paris Agreement and halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030 under the Global Biodiversity Framework.

Banks and other financial institutions should:

- Suspend services, financing and contracts with Cargill until the company can demonstrate a credible plan to meet its zero deforestation targets and prevent all illegal deforestation in its supply chain.

- Review client relationships with Cargill and its subsidiaries as part of a process of ongoing due diligence to prevent the financing of deforestation and laundering of the proceeds.

Cargill should:

- Honour the New York Declaration on Forests commitment, adopt a 2020 cut-off date for soy cultivated on deforested land and a 2025 target date for deforestation-free soy supply chains in line with best practice, and expand its organizational zero deforestation targets and strategies to include all biomes in Bolivia, including the Chiquitano.

- Immediately implement full traceability requirements for all soy cultivation, purchases and processing in Bolivia.

- Record and publish transparent information about the origins of its soy supply chain in Bolivia.

- Commission an independent audit of its Bolivian soy purchases, to identify and remedy the scale of ecosystem and social harm.

- Ensure the Agriculture Sector Roadmap to 1.5c is expanded to cover 2025 targets and appropriate retrospective cut off dates for deforestation-free supply chains across all biomes and all forest-risk commodities, including Bolivia’s Chiquitano.

The Bolivian government should:

- Honour its commitment to defend “Mother Earth”, in particular the requirement in the 2012 law to protect primary forests, manage them sustainably, and ban their conversion to other land uses. This should include an immediate moratorium on cutting down forest that is not suitable for agricultural purposes.

- Regulate the soy and other agricultural products sectors so that full traceability from point-of-harvest to processing mill and/or export is required for all operators.

- Reverse the program of environmental deregulation and instead prioritise laws and policies protecting the environment and human rights.

- Update the forestry laws, regulations and policies in accordance with the 2009 Constitution, so that they are accorded the same importance as the country’s agrarian policies and practices.

- Join the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use and join the Forest and Climate Leader’s Partnership initiative to collaborate in a collective effort to end deforestation and land conversion by 2030.

Methodology

Global Witness determined Santa Cruz in Bolivia as a region of interest for our investigation by analysing satellite data to identify deforestation events linked to soy planting and cultivation since 2017. Based on that initial analysis, we overlayed a dataset developed by McGill University which includes the boundaries of Mennonite colonies in South America [1], with deforestation data from Global Forest Watch [2], which uses satellite data (namely GLAD and RADD forest canopy change alerts), in order to ascertain levels of conversion from forest to soy fields within the colonies. Global Witness used mapping software (QGIS to measure the extent of deforestation in hectares within the Mennonite boundaries mentioned in this report (see map 1). This analysis informed the geographic focus of our two field visits to Bolivia. The link between soybean production and sales by the Mennonite colonies and Cargill were established through extensive local interviews, site visits and receipts photographed by our researchers, as detailed throughout the report.

[1] Polain de Waroux, Yann le, Janice Neumann, Anna O’Driscoll, and Kerstin Schreiber. “Pious Pioneers: The Expansion of Mennonite Colonies in Latin America.” Journal of Land Use Science, December 15, 2020, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/1747423X.2020.1855266 (https://borealisdata.ca/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.5683/SP2/I4FEQZ).

[2] Global Forest Watch, https://data.globalforestwatch.org/documents/941f17325a494ed78c4817f9bb20f33a/explore

- Download the full report: Empty promises (4.0 MB), pdf