Amidst the vast and diverse landscapes of Brazil lies a vast savannah ecosystem called the Cerrado.

Often overshadowed by the grandeur of its north-westerly neighbour, the Amazon rainforest, the Cerrado comprises around a fifth of Brazil's territory and plays a critical role in the regional ecosystem.

The biome boasts astonishing biodiversity - with more than 11,000 plant species, 860 bird species, and countless other flora and fauna finding a home within its unique mosaic of scattered trees, woodlands, grasslands, and streams.

Brazil’s “upside down forest”

Despite its sparce nature above ground, the Cerrado has vast underground roots helping its plants survive seasonal droughts and fires.

These subterranean riches also mean the area serves as a powerful carbon sink, burying around five times more CO2 within its roots and soil than above ground, giving it the nickname “the upside-down forest”.

As of 2017, the Cerrado is said to hold 13.7 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide - more than China released in 2020.

The Cerrado also goes by another nickname: ‘the cradle of waters’ – named so for its function as a vital water tower, allowing it to regulate rivers that nourish downstream ecosystems, and acting as a source of many of the country’s major rivers.

Under pressure

But the Cerrado faces significant pressures from human activities. Driven by global demand for agricultural products like soybeans and beef, land conversion for large-scale agriculture and cattle ranching is posing a major threat.

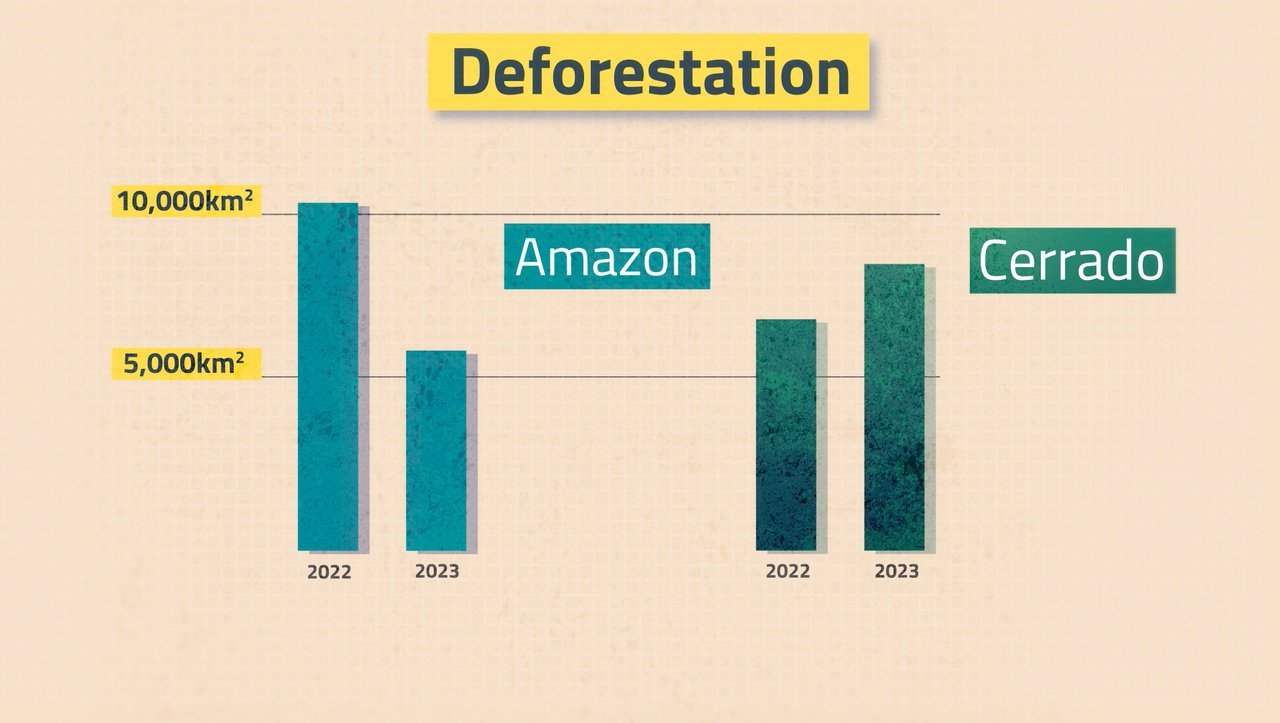

In fact, while the Brazilian Amazon’s annual deforestation rate fell by half in 2023, the Cerrado’s increased by 43%.

This extensive deforestation is disrupting natural habitats, jeopardizing biodiversity, and altering the Cerrado's crucial role in water regulation and carbon storage.

It is hard to overstate the importance of the Cerrado for the earth’s climate, with the UN climate target of liming global heating to 1.5C said to be put out of reach if its destruction continues.

Beyond its ecological importance, the Cerrado is also essential for social justice and cultural preservation, with the immense open-canopy woodland home to or relied upon by many Indigenous and traditional communities, including Quilombolas (descendants of runaway slaves) and Ribeirinhos (riverside dwellers).

But the lands and livelihoods of local communities are now at risk.

What can be done to protect the Cerrado?

There is currently a widespread failure to acknowledge the importance of the Cerrado for biodiversity, water security, climate stability, and its inhabitants.

While we’ve seen the positive impact of political pressure and policies on biomes like the Amazon, the Cerrado is relatively unprotected by laws and voluntary agreements. As of 2021 less than 8% of the Cerrado is legally protected against deforestation, compared to nearly half the Amazon.

Significantly, three-quarters of the Cerrado currently falls outside the scope of the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), the bloc’s ground-breaking law banning the trade in commodities produced on deforested land.

Without adequate protection, the Cerrado is becoming an ecological “sacrifice zone”.

In 2024, the European Union is set to debate whether to include more of the Cerrado in its deforestation policy by recognising the importance of biomes that fall outside of the tradition ‘forest’ category, and under ‘other wooded land’.

The EU and governments around the world must act urgently to introduce and strengthen laws that stop products tainted with deforestation - from the Cerrado and beyond - ending up on our supermarket shelves.

On top of this, agribusiness giants linked to deforestation in the Cerrado - like JBS, Minerva and Marfrig - must also eliminate all deforestation in their supply chains.

Until they do, global financial centres must withdraw their financial support for them.