Photo: Flickr/Creative Commons, esteban_monclova

How Shell, Eni and Exxon got embroiled in shady oil deals and corruption scandals around the world and what the US can do about it.

This week, together with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Global Witness co-hosted a wide-ranging discussion on oil corruption, why it matters and how the US government – and companies – can be part of the solution. Here’s what you need to know (for those who couldn’t join, you can also check out a recording of the live C-Span broadcast).

The oil, gas and mining industry ranks as the most corrupt sector on the planet, according to international statistics. The three panellists – Simon Taylor (Global Witness co-founding director), Steve Coll (Pulitzer Prize-winning New Yorker staff writer) and Olarenwaju Suraju (Nigerian anti-corruption and environmental activist) – all painted a compelling picture of this global problem. Simon Taylor kicked off the discussion by outlining one of the biggest corruption scandals in the history of the oil sector: our investigation into the vast 1.1 billion-dollar bribery scheme that Shell took part in – a deal that robbed the Nigerian people of money that should have gone to building schools, hospitals and infrastructure. Leaked Shell emails show that senior Shell executives knew that their money would likely be used to pay off top Nigerian officials – yet, they still proceeded with the deal. The case is progressing through the Italian and Nigerian courts with Shell, Italian oil giant Eni and Eni’s most senior executives facing trial on bribery offences on what could become the biggest corporate corruption trial in history.

Leading US journalist Steve Coll, who has extensively investigated ExxonMobil, placed this Nigeria case within the larger picture of oil geopolitics, drawing on his reporting in Chad and Equatorial Guinea. Nigerian anti-corruption activist Olarenwaju Suraju underscored that corruption in Nigeria should not be blamed on corrupt Nigerian public officials alone – it could not happen without malfeasance by foreign corporations like Shell and Exxon; bribery takes two to tango. He outlined an ongoing corruption investigation into ExxonMobil’s renewal of three major oil licenses in Nigeria at a fraction of the price its Chinese competitor was offering to pay.

Suraju also argued that corruption should be recognized as a central factor in the rise of terrorist movements like Boko Haram – the funds that are lost to corruption could have built schools and paid for education for the scores of Nigerian children who instead joined these movements.

So what are the solutions to this global oil corruption curse? Simon Taylor called for more meaningful legal accountability in cases such as the Shell scandal, rather than the status quo where corporations routinely negotiate favorable agreements with prosecutors to pay fines that are, at best, seen as merely a cost of doing business.

Taylor also pointed out that companies could likely be deterred from making these kinds of questionable payments if they were required to disclose them in sufficient detail. Steve Coll echoed the call for transparency and lamented that the current US administration is rolling back progress achieved under the Bush and Obama administrations, citing its rush to repeal a key oil, gas and mining transparency regulation and signals it may withdraw from the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, in what he described as a departure from previous Republican policy.

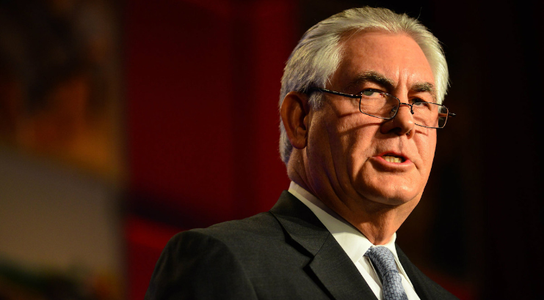

This is hardly a coincidence. As Taylor pointed out, both of these transparency measures have been actively opposed and undermined by ExxonMobil, including specifically by its former CEO and current US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. Carnegie expert Sarah Chayes, who moderated the discussion and studies the rise of kleptocratic networks around the world, remarked that Tillerson’s appointment as US Secretary of State raised concerns for her because it signalled a dangerous overlap of public and private sectors that she sees in other countries she has studied, like Honduras and Azerbaijan.

Indeed, while we have seen Tillerson’s performance in his new post to be both underwhelming and alarming, we have also seen that Big Oil interests are getting their way in gutting key US anti-corruption and environmental measures. These rollbacks of key measures make America an outlier and laggard, after years of global leadership. This can only serve to hurt US interests – as Steve Coll remarked with reference to climate change: whatever America does won’t change global public opinion, and we’ll eventually have to catch up with the rest of the world.