Hydrogen could be an important part of the renewable energy transition, but not if the fossil fuel industry has its way.

At first glance, hydrogen seems to be the perfect solution to our energy needs. It doesn’t produce any carbon dioxide when used. It can store energy for long periods of time. It doesn’t leave behind hazardous waste materials, like nuclear does. And it doesn’t require large swathes of land to be flooded, like hydroelectricity.

All in all, hydrogen seems too good to be true. No wonder the energy industry is currently pushing hydrogen as the fuel of the future. So…what’s the catch?

Not all hydrogen is created equal

While it’s true that hydrogen is carbon-free at the point of use, this only tells part of the story. Before we get to the stage where hydrogen is used, it first needs to be produced. And it’s this process where the complications begin.

There are several different ways of producing hydrogen, with varying levels of carbon intensity. One is to pass an electric current through water, splitting the water molecules apart into their constituent hydrogen and oxygen atoms. With this method, the key is what kind of electricity you’re using to create the electric current. If the electricity is from renewable sources, then the overall process will be effectively carbon free. If you’re using electricity generated by burning fossil fuels, then the hydrogen will be very carbon intensive.

The other method is to mix natural gas (or as we prefer to call it, fossil gas) with steam. This method currently accounts for 98% of all hydrogen production. While not as bad as using electricity generated using fossil fuels, the process still releases huge amounts of carbon – each tonne of hydrogen produced releases eleven tonnes of CO2, equivalent to driving 72,000 km in a passenger car.

“Blue hydrogen” is a dead end

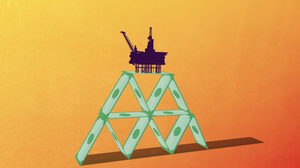

Fossil fuel companies know that their days are numbered. As, slowly but surely, governments accelerate the changes to our energy system required to tackle the climate crisis, sales of fossil fuels will fall and production of renewables will ramp up. This is bad news for companies which have invested a lot of money into building infrastructure for the extraction and transportation of fossil fuels, which may no longer be needed well before the end of its natural life cycle.

As it’s become clear that the days of coal and oil are numbered, fossil fuel companies have increasingly shifted their focus to fossil gas. And now they’re worried that gas, too, will go the same way. So they’re pinning their hopes on hydrogen made using fossil gas in a last-ditch attempt to keep their industry alive.

These companies are putting a lot of effort into pushing the idea of hydrogen as the clean, green fuel of the future. The problem, of course, is that their chosen method of producing hydrogen still releases a lot of CO2.

To get around this, the fossil fuel industry is claiming that they can capture the carbon emissions released during hydrogen production, and store them safely underground where they can’t contribute to global heating. Fossil fuel companies like to call this 'blue hydrogen'.

Hydrogen colour codes

Different methods of producing hydrogen are often referred to by certain colours:

Grey hydrogen – Produced by mixing fossil gas with steam. Releases large quantities of CO2.

Blue hydrogen – Produced using the same method as grey hydrogen, but with carbon emissions supposedly captured and stored underground. Yet to be proven at any significant scale. Both grey and blue hydrogen are more accurately called ‘fossil hydrogen’.

Green hydrogen – Produced by passing electricity generated from renewable sources through water. Results in very low carbon emissions.

However, there is no evidence that these carbon capture plans will be able to work at anything like the scale or level of efficiency required to mitigate the emissions from fossil hydrogen. In fact, when we looked into one of the only operational fossil hydrogen plants using carbon capture technology in the world, we found this technology to be severely lacking.

Shell’s Quest site in Alberta, Canada, has been lauded by the company as an example of how it is taking action on the climate crisis. However, just 48% of the plant’s carbon emissions are captured, falling woefully short of the 90% carbon capture rate promised by fossil hydrogen advocates. When the plant’s overall greenhouse gas emissions are factored in, it has the same carbon footprint as 1.2 million petrol cars.

Renewable hydrogen has a (small) role to play

Despite the problems mentioned above, hydrogen does have an important role to play in the renewable energy transition. But not at the scale the fossil fuel industry is claiming.

When produced using renewable electricity, hydrogen could be an invaluable tool to decarbonise sectors which are difficult to electrify, such as steelmaking, and to store energy from renewables when their supply is scarce.

But aside from some limited uses, for the most part it is both cheaper and more efficient to simply use renewable electricity directly, rather than adding the extra step of producing hydrogen. For this reason, renewable hydrogen does have a place in the future energy mix, but a limited one. Our efforts are much better spent cutting energy demand, ramping up renewables, and electrifying as much as possible.

Fossil fuel lobbyists are claiming that hydrogen could provide up to a quarter of the EU’s energy by 2050 – up from just 2% today – and are encouraging the EU and national governments in Europe to fund the construction of hydrogen infrastructure in line with this figure. This risks locking us into hydrogen dependency, increasing demand for hydrogen above what can (or reasonably should) be produced with renewables, to a level that can only be filled by fossil hydrogen.

This wouldn’t help us reach our climate targets, and in fact the vast amount of CO2 released through fossil hydrogen production would only move us further away from them. The only people it would help are fossil fuel companies who are trying every trick in the book to prop up their dying industry, and avoid the long overdue debate about winding down the fossil gas industry.