A month ago, on the afternoon of 6 January the former President of the United States told his supporters to show strength and ‘stop the steal’. Goaded on by his lawyer who suggested ‘trial by combat’, rioters breached the Capitol in an attempt to overthrow the result of the election. Five people lost their lives in the violence.

Arrests were made and the President was impeached, again. But perhaps more galling to him was to be denied his online platform. Following the insurrection he was de-throned from Twitter and suspended from YouTube and Facebook. Parler, a platform favoured by the far-right and used by many who rioted that day, was swiftly denied access to Amazon’s web-hosting services, while another - Gab - saw a huge spike in members.

While it was right for the platforms to remove Trump given his role in inciting the violence on the Capitol, it has highlighted another deeply unsettling problem: that far too much power lies in the hands of handful of tech execs and they shouldn't be the ones to arbitrarily decide who gets a platform online.

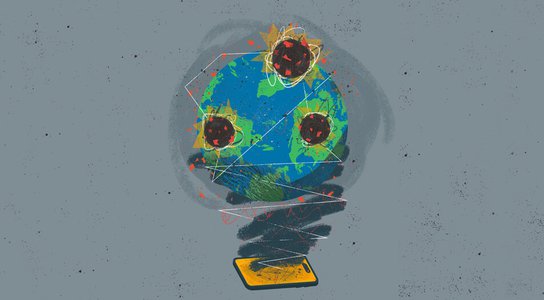

The online repercussions of the insurrection have put the power and reach of Big Tech in the spotlight. Their role in amplifying extremism is under renewed scrutiny from both sides of the American political divide.

On a practical level, online platforms provided a space for rioters to recruit, organise, and fundraise ahead of 6 January. But their role in contributing to the spread of lies that underwrote the insurrection far predates January 2021.

To understand this it helps to understand how Facebook, Google and Twitter, make money: they sell advertising. And their near monopoly status means that users feel locked in to the platforms and advertisers are reliant on them to connect with consumers.

Their business model means that they are financially motivated to promote engagement and keep people on their platforms for as long as possible. After all, the more time we spend on a platform the more data we reveal; the more data we reveal, the more detailed our profiles are, the more they have to gain.

With this level of sensitive and personal information at their disposal platforms can sell advertisers the ability to target goods and messages at extremely narrow segments of users, ‘micro-targeting’ us based on our demographics, actual or even predicted behaviour, and personal characteristics.

Research shows that anger is the emotion that travels fastest and furthest on social media, and that lies travel six times as fast as the truth. It follows that tilting public attention towards hateful content via algorithms designed to increase engagement is a means to maximise profit.

These are the conditions in which the former President excelled: his dog-whistle approval of fascists and white supremacist militia, succinct slogans, and willingness to incite outrage are an ideal fit for an information ecosystem that prioritises engagement over public health, security, and facts.

So though the platforms did not start the pernicious lies that have taken hold, once spewed from the White House their algorithms amplified them, virally accelerating their spread online where they were amplified in turn by traditional media such as the former President’s cheerleaders at Fox News.

This describes the polarisation we see as a by-product of platforms whose profits depend on engagement.

But the platforms go further and in our view become more culpable for enabling political division and extremism when they sell advertisers the ability to micro-target their messages.

Allow political adverts - whether Republican or Democrat, progressive or conservative - to be personalised and targeted at narrow groups of voters based on their behaviour and demographics, and you allow inflammatory messages to be spread in the shadows, limiting the opportunity for counter speech and creating the potential for political promises to be made in bad faith.

In their infancy social media platforms were imagined as a public square where citizens could connect, organise, and debate in the open. And now, decades on the picture has become more complicated: the rioters connected and organised on these platforms, but so did those who reached out to neighbours in the midst of a global pandemic and showed up in solidarity with Black Lives Matter. Similarly, following the military coup in Myanmar, activists are being thwarted in their ability to organise after Facebook was switched off.

To maintain the best of what platforms can offer, to redeem our democracies and have any hope of tackling collective threats like the climate crisis requires good faith debate, an agreement on the facts, and for politicians to make promises in the open and be held accountable for them.

This is why we’re calling for governments to restrict the ways that political adverts can be targeted and to force platforms to be transparent about how and why people are seeing adverts about political and social issues.

We know that this is not a silver bullet - this one policy will not heal the populist divisions that have flourished globally over the past decade and will not tackle the power and might of Big Tech giants which hoover up our data for profit. But we believe it is an essential first step if we are to find common ground and forge a political discourse that works for us all.

Author

-

Naomi Hirst

Senior Campaigner, Digital Threats