After two years since the regional instrument entered into force in the Americas, the country continues to face enormous challenges as communities defend Mexico's land and environmental heritage.

According to the Global Witness’ latest annual report on land and environmental defenders, 54 environmentalists went missing or were murdered in Mexico in 2021. The country topped the list for the first time since 2012 with the highest number of killings of defenders in 2021 globally with an increase in lethal attacks for the third year in a row.

This trend is shocking, and its consequences deeply shatter every community and movement affected.

The violent attacks are not confined to environmental activists: Mexico topped the list of murders of journalists for the fourth consecutive year in 2022, with 11 murders. Both journalists and defenders are scorned and attacked by the political sector in Mexico, which often portrays them as enemies of progress.

Why does this happen in Mexico? Is it because there are no laws? No. This is a country that signs onto almost every international human rights instrument and recognises human rights at the highest level of law but lacks the capacity –and the political will– to implement them.

On 22 January 2021, Mexico and Argentina submitted the ratification of the Escazú Agreement to the United Nations in New York. The importance of this act was far-reaching, as it triggered the Agreement coming into force from April 2021 onwards.

This regional Agreement for the Americas aims to ensure access to environmental information, public participation in environmental decision-making, and access to environmental justice. This Agreement is also the first treaty with provisions to protect environmental defenders. However, between 2017 and 2021, attacks rose sharply, affecting those on the frontline defending their rights against irresponsible industries and other actors, such as militias, organised crime, and drug trafficking networks. Documented attacks against defenders have increased exponentially, affecting the protection of Mexico’s natural heritage.

Mexico signed the Escazú Agreement in 2018. That same year Global Witness registered 14 cases, whereas, in 2020, when it ratified the instrument before congress, the number of killings had doubled to 30.

I have first-hand experience in witnessing the tragic killings of defenders in Mexico. I received a message in the early morning of 4 April 2021. A friend told me that the Indigenous leader and environmental rights defender, José Santos Isaac Chávez, had been kidnapped in the heart of the mountains that connect the states of Colima and Jalisco. José had decided to seek justice for his community in Ayotitlán. That choice should not be risky, but it cost him his life. A few days after, he was found dead.

The community has been suffering from environmental harms linked to the country's largest iron mining company with international links in Europe. Its operations have aroused clear opposition from the communities amidst illegal mining by drug cartels, corruption among government authorities, and the supremacy of organised crime.

The impact of the attacks is palpable. This killing sums up the struggles of a community of more than 13,000 people who feel under siege in a territory where they are isolated with restrictions on their movements – the routes are controlled– as well as access to information that enters and leaves the place.

"This is a silenced area, where those who raise their voices are attacked and receive death threats, which, as in the case of José Santos Isaac Chávez, can be lethal, disappearances and murders." - Eduardo Mosqueda

Escazú turns two in Mexico: how far have we come?

A good starting point is to assess how far Mexico has come since ratifying this agreement, which focuses on access to information, participation in environmental matters, transparency, preventing attacks and justice for those involved in defending environmental issues.First, one of the most worrisome issues is the murders of journalists, which, as they themselves report, are carried out to silence the truth that they reveal in their publications. This affects coverage of environmental issues, particularly when they represent power struggles. Access to information is undermined if the testimonies and investigations of those who suffer the consequences of abusive powers are left in the dark.

The need for environmental impact studies on megaprojects spearheaded by the current administration adds to the opacity of its dealings. It, therefore, hampers the capacity to advocate for those of us who work with grassroots communities affected or potentially exposed to the consequences of their installation.

For example, the Mayan Train project is a large-scale project that will impact ancestral territories, preserved environments and the livelihoods of thousands of people in the southeast of the country. Yet it has been carried out without the consultation standards set by the International Labour Organisation (ILO). What’s more: the federal decree of 22 November 2021 enabled the government to grant a "provisional" concession to operate without reporting on the impacts of the projects. The executive's decisions leave those with doubts and evidence to oppose significant disruptions to their territories on the side-lines.

On the other hand, Mexico lacks sufficient specialised environmental courts. There is only one specialised chamber of the Federal Court of Administrative Justice in Mexico City, to deal with over 560 socio-environmental conflicts recognised by the government. This is far from complying with the law's stipulations, which require that these courts be located throughout the country. Likewise, in Mexico, there is no integral remedy for communities affected by a project. The current regulatory framework addresses the restitution of rights but misses out international standards that also call for restoration, compensation, satisfaction and guarantees of non-repetition as elements of integral reparation.

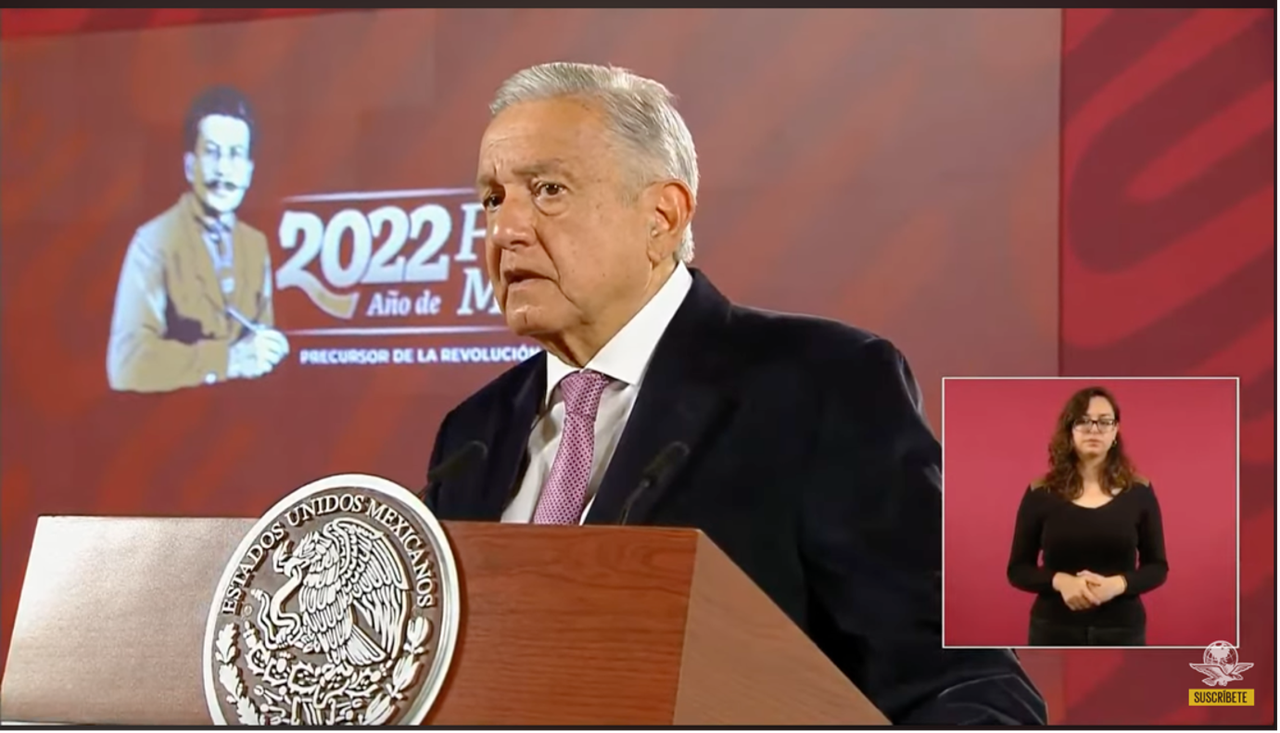

The deterioration of public participation and, therefore, protection of environmental and land defenders is evident: Civicus described civic space in Mexico as repressed due to the use of a public discourse that undermines the role of defenders. It goes from the highest level of public officials, including its president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador. During open sessions for the press –called “Mañaneras” – President López Obrador has described activists as part of conspiracies and environmental defenders and organisations as "foreign agents".

The UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders, Mary Lawlor, has been clear: to control the message is also to control the possibility that these agents of change can do their work.

In the meantime, most of the deadly crimes against environmental activists remain unpunished. The Federal Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists – a framework for responding to and preventing further attacks against defenders- has seen its independence undermined by the lack of sufficient funds to operate under the premise of fiscal austerity, exacerbating the risks for those on the frontline.

On 7 October 2022, he referred to members of civil society as pseudo-human rights defenders and pseudo-environmentalists, accusing them of getting profits out of the victims of the human rights crisis across the country.

Key actions for the defence of the environment

The effective implementation of the Escazú Agreement will transform our ability to defend our common home, Mother Earth.

There is no easy solution, but there are key steps that must be taken:

Recognise that it is necessary to build and uphold alliances at local, national and international levels.

Understand the context in order to do a risk and threat analysis alongside security planning to identify vulnerabilities.

Create a comprehensive strategy among all parties involved to maximise efforts to demand justice.

All of the above must come along with a State that is ultimately responsible for creating a safe environment for defenders and civic space to develop. This must be in harmony with regulations that raise the standards to approve projects that may affect ecosystems and those who inhabit them.

Because to achieve the best possible outcome we must recognise ourselves as part of a global community, building from the local, until dignity becomes practice.

*Tsikini AC is a non-profit organisation seeking to promote access to justice to communities vulnerable to the human rights and environmental impact of businesses and mega projects in Jalisco, México.

Author

-

Eduardo Mosqueda

Executive Director of Tsikini A.C*