Europe’s flawed anti-money laundering framework enables kleptocrat rulers and their families to loot their own country

When I speak about my work on the Republic of Congo, an oil-rich Central African country, people are quick to acknowledge corruption as a pressing issue for the country. However, very few recognise the crucial role played by European countries in facilitating this corruption.

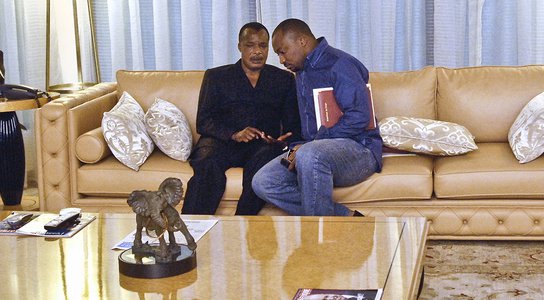

José Veiga (right), a Portuguese businessman who is the target of a Portuguese investigation into corrupt deals in Congo. He acted as a frontman for Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso (left).

In recent months, I’ve published investigations revealing how Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso and Claudia Sassou-Nguesso, son and daughter of Congo’s President and elected members of the Congolese parliament, apparently stole over $70 million from state coffers for their personal gain.

To piece together the investigations, I followed the money -

trawling through numerous bank statements, corporate documents and secret

contracts, and speaking with sources in many different countries.

The investigative trail led me right to the heart of Europe, with seven different European countries involved in a scheme that bears all the hallmarks of money laundering.

It’s not exactly easy to stash away $70 million in bags of cash. Instead, in order to hide the tainted public money and freely spend it, the President’s kids set up a complex network across Europe. Here’s what they did:

- Picked a Portuguese businessman to act as a nominee (a ‘frontman’);

- Moved $70 million of Congolese public funds through a network of at least 10 shell companies set up in Cyprus, Estonia and Spain;

- Spent the money in Poland, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland and United Kingdom, according to a police report.

All these countries played a key part in the scheme, most likely enabling the Sassou-Nguessos to enjoy the spoils of their dirty money in Europe.

Because operations like those set up by the Sassou-Nguessos are explicitly designed to make it difficult to trace and track tainted money, it is hard to pin down what the President’s children purchased across Europe.

Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso’s hidden Cypriot shell company, which received tens of millions of dollars, is registered at this address in Nicosia, Cyprus

© Global Witness

But the Sassou-Nguessos are notorious for spending vast sums on luxury goods and properties and living a lifestyle which is not compatible with a public official’s salary in Congo.

In April, my investigation revealed how Claudia Sassou-Nguesso used a portion of the public funds she seemingly stole to purchase a luxury apartment in Trump International Hotel & Tower in New York.

In 2007, Global Witness, uncovered how Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso appeared to have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars of public money on luxurious designer shopping sprees in France and Spain.

French investigators looking into the Congolese Presidential family’s assets found that they had spent at least $67.6 million on luxury goods and properties in France.

Given this track record, it is likely that the money Claudia and Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso appear to have stolen from Congo’s treasury and spent in Europe was used to pay for their lavish lifestyles.

While this is happening, a third of Congo’s population lives below the poverty line and citizens go months without wages, pensions and vital medicines.

The flows of money between the 10 shell companies owned by the Sassou-Nguesso siblings in Europe should have been a red flag for authorities. By turning a blind eye and asking no questions when suspicious money comes its way, Europe is also partly responsible for the tens of millions of dollars stolen from Congolese citizens.

In the case of the Cypriot companies secretly-owned by the President’s kids, a transfer of ownership from the Portuguese frontman to the Sassou-Nguessos was stamped and made official by a notary in Congo’s capital, Brazzaville. No indication of the transfer was made in Cyprus, the country of incorporation. This means that anyone trying to identify the company’s owner in Cyprus would be fooled.

To tackle this, European countries should fully implement requirements for all companies formed in Europe to disclose publicly who ultimately owns and controls them. EU Members states are required to implement public registers of company ownership by January 2020.

But we urgently need more enforcement action and to consider new European rules to fill the existing gaps. If not, corrupt politicians like the Sassou-Nguessos will be able to continue to hide and disguise their control of shell companies in order to stash their dirty cash abroad.