The UN's COP29 climate summit in Baku, Azerbaijan will focus on climate finance and raising funds for developing countries affected by the climate crisis

What is COP?

COP stands for “Conference of the Parties", which is a generic phrase in International Relations-speak meaning a committee created after an international treaty is signed, tasked with making decisions about how that treaty is implemented.

There are all kinds of COPs for various international agreements, from chemical weapons to combatting desertification.

But the term COP has come to be associated with the meetings of one particular committee: that created after the signing of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

A total of 154 countries signed the UNFCCC in June 1992, agreeing to combat harmful human impacts on the climate.

Since then, COP meetings have been held (almost) annually to discuss how exactly that should be achieved, and monitor what progress has been made.

Each COP is usually referred to by its number in the series, e.g. COP26 was the 26th COP meeting.

Each year a different country becomes the COP president, in charge of organising and running that year’s meeting. Usually this means that the host city moves each year, too.

Any new agreements that are made at COP tend to be named after the host city, e.g. the 2015 Paris Agreement or the 2021 Glasgow Climate Pact.

Who is involved in COP?

We often hear about politicians, diplomats and national government representatives being invited to COP, but they are far from being the only ones who attend the conference. Many others join, aiming to influence the outcome – some to push forward climate action and justice, others to advance their own interests.

For example, many fossil fuel lobbyists join the talks to attempt to protect their industry from much-needed action to keep coal, oil and gas in the ground.

At COP27, we found that there were twice as many fossil fuel lobbyists as delegates from the official UN constituency for Indigenous Peoples. And at COP28 in Dubai, we found a record number of industry lobbyists, with nearly 2,500 descending on the talks.

On the opposing side, there are land and environmental defenders, including Indigenous Peoples, calling for greater protections for their territories against exploitation by environmentally destructive industries such as logging, mining and industrial agribusiness.

Climate organisations such as Global Witness attend with partners to advocate for rapid and ambitious action to tackle the climate crisis, while ensuring a just transition.

However, there are often barriers in place – regulatory, economic, legal and physical – which prevent environmental activists and civil society organisations from meaningfully participating in these global decision-making processes.

Unfortunately, those most affected by climate emergency are not the ones who have the final say at the conference.

What was agreed at COP28 last year?

After a damning verdict from the first ever Global Stocktake (an assessment of how on track countries are to fulfil 2016’s Paris Climate Change Agreement), countries at the climate summit in Dubai renewed their commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

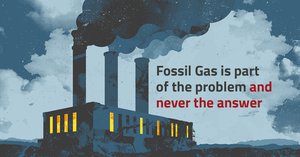

For the first time in 28 years of negotiations, nearly 200 countries agreed to “transition away” from fossil fuels. COP28’s president, Sultan Al-Jaber, applauded the move as “historic”, but the devil is in the detail.

Countries arguing for a “phase out” of fossil fuels were met with resistance from a coalition of petrostates – including Saudi Arabia and Russia – who ensured that the text of the final pledge was diluted.

In the absence of an explicit call for a “phase out” (or even the less stringent “phase down”), and with no legally binding document in play, the fossil fuel industry still has plenty of leeway to continue with business as usual.

For example, a Global Witness investigation found that ADNOC (the United Arab Emirates’ state-run petrochemicals company, which Al-Jaber steers as CEO), sought up to $100 billion of fossil fuel deals in UAE’s year as COP28 host – a four-times increase on its dealmaking the year before.

Leaders at the climate summit also agreed a net zero food plan, which would see the world’s food systems overhauled to become a carbon sink by 2050.

Yet, the declaration failed to mention the role of agriculture in driving over 90% of tropical deforestation.

What will be discussed at COP29 this year?

Dubbed the “finance COP”, a core theme of COP29 will be dramatically scaling up every country’s climate ambitions – and finding the necessary funds to pay for them.

Four key words will dominate negotiations at Baku’s climate summit: loss, damage, adaptation and mitigation.

These refer to the four pillars of climate action, where countries fund new infrastructure to protect people against the worst effects of climate change, transition to new net zero technologies and systems, and, where those adaptations fail, pay for recovery from climate-related disasters.

Summit host Azerbaijan has named several priorities focused around raising funds to enable climate action:

- A New Collective Quantified Goal on climate finance: In 2009, delegates reached a landmark agreement to raise $100 billion by 2020, which would help climate-vulnerable countries adapt to the challenges of the climate crisis. A new target will be set this year in Baku based on the evolving needs of these nations.

- Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage: The loss and damage fund will help low-income countries pay for recovery from climate-related disasters, which no amount of mitigation or adaptation could have prevented. Given the potential overlap with the New Collective Quantified Goal, which also covers loss and damage, COP29 will see countries debate what specifically the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage should respond to.

- Updated National Determined Contributions (NDCs): Crucial to staying within the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C global heating threshold are each country’s individual efforts to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, known as NDCs. Every five years, countries must submit revised NDCs to the UNFCCC secretariat, adapting their projected targets and actions to the evolving climate emergency. Baku will be an opportunity for countries to collectively think bigger before they resubmit in 2025.

- Article 6 of the Paris Agreement: Countries will debate the details of how to meet their climate goals through non-market and market-based solutions, particularly the carbon tax credits market. At COP29, nations will discuss how to regulate carbon credits. Some prefer a less restricted market, while others advocate for stronger rules to ensure transparency and protect human rights. These decisions will be crucial in shaping climate finance and global climate action.

What are the contentious issues at this year’s COP?

Having named climate finance as a core topic at COP29, the climate summit’s success will depend on how well it can navigate tensions over who pays, who gets to benefit and how tightly climate innovations and markets should be controlled.

Who should pay (and how much)?

One sticking point in previous negotiations has been how much responsibility high-income countries should shoulder for raising climate finances.

Some high-income countries have argued that the historic division of nations into developed and developing should no longer apply, given the accelerating economies of some developing countries like China and India.

Negotiators have also said that the sizeable greenhouse gas emissions of these emerging economies should make them eligible to pay into the New Collective Quantified Goal.

But developing countries insist that the cumulative greenhouse gas emissions wealthier countries have produced since pre-industrial times means they should answer for the eyewatering costs that climate-vulnerable countries now face.

This is especially pertinent for the loss and damage fund – a long overdue success story from COP28, whose operational details now need to be ironed out.

We’ll be watching to see whether high-income countries follow through on their obligations to those facing the brunt of the climate crisis – and just how generous they choose to be with their financial pledges.

Developed countries have historically dragged their feet on climate finance, only reaching the target $100 billion in 2022 – two years overdue and falling far short of renewed estimates of how much climate finance is needed globally.

The UNCTAD has suggested $500 billion as a floor to launch from in 2025, with the goal of raising $1.5 trillion by 2030. The think tank Climate Policy Initiative meanwhile estimates that $9 trillion in climate finance will be required every year by 2030, jumping to $10 trillion between 2031 and 2050.

Regulating private and climate finance

As the search for climate finance continues apace, we’ll be pointing out that not all finance is good. Those responsible for financing destruction – for example the destruction of climate-critical forests – should be held to account and subject to new laws.

On the voluntary carbon markets front, we’ve written before about the pitfalls of relying on carbon offsets to preserve biodiversity and reduce carbon emissions.

But if countries are to use the carbon tax credit market to raise climate finances, it is vital that they settle on a regulated market. Transparency, proven additionality and shared standards about acceptable projects and carbon credit values must be central tenets.

People before polluters

As negotiators unpick these thorny issues, we’ll keep calling for human rights to be front and centre of all discussions. Neither ambition nor fundraising should threaten communities on the climate crisis’s frontline, including Indigenous Peoples and land and environmental defenders.

COP28 marked the first time nations have agreed upon the direction of travel for fossil fuels. But the final agreement gave far to much leeway for big polluters to continue business as usual.

COP29 must now ramp up ambition and action towards a cleaner, greener, more equitable world without unseating its commitment to climate justice.

Follow us to keep up to date with our latest COP news and campaign activities.