This blog post originally appeared in The Huffington Post.

Pour lire en français cliquez ici.

Co-authored with Norbert Mbu Mputu, Congolese activist and President of the Southern Peoples Project

Nine years since the first international warrant for his arrest, the warlord Bosco Ntaganda will today go on trial at the International Criminal Court in The Hague. He is charged with committing 18 counts of war crimes in Democratic Republic of Congo (Congo), including murder, rape, pillage, and the conscription of child soldiers. But, even this scandalous rap sheet does not reveal the full extent of Bosco's alleged crimes: his clandestine and illegal dealings in the region's minerals trade remain little examined.

Bosco's violent activities caught the world's attention long before he ceremoniously handed himself in to the US Embassy in Rwanda, two years ago. It's not hard to see why. He is charged with leading ethnically-motivated murders: killing his victims with bullets, arrows, and nail-studded sticks. The Congolese population bore the brunt of his abuses, while he was covered in the media dining in lavish restaurants and in luxury hotels. The press nicknamed him 'The Terminator' because of the horrors he authored. Ntaganda has not yet entered a plea.

But away from the headlines, Bosco got rich off Congo's minerals. He owned mines and illegally taxed mineral trading routes. Campaigning organisation Global Witness has reported how he oversaw a massive smuggling operation that funnelled minerals into Rwanda, via his own private residence strategically situated on the border. In 2011, the United Nations Group of Experts on the Congo estimated that Bosco's mineral smuggling empire earned him around US$15,000 per week. A year later, one minerals trader in eastern Congo told Global Witness researchers "Bosco is never visible but...controls all the networks. You can't get anything across [the border] without [his] facilitation".

The fluctuating nature of Congo's war alliances - where enemies can quickly become partners and vice versa - allowed Bosco to become extremely powerful and wealthy. Crossing over from rebel to army General in a 2009 backdoor peace deal cemented his control over lucrative mining zones, allowing him to effectively run his own state-within-a-state. This despite the fact Congolese law deems the involvement of the army in the minerals trade illegal.

The battle lines in this protracted conflict are complex, with rivalries tied into competing claims over land, bitter ethnic conflict, and political ambition. But many of these groups, as with Bosco, have part financed themselves and their campaigns through the illegal sale, smuggling or taxation of eastern Congo's minerals - especially tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold. These minerals are then traded internationally.

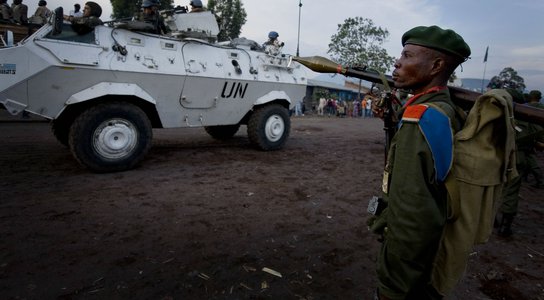

Bosco might be facing trial today, but armed control over Congo's minerals has not gone away; armed men continue to control mines and territory in the country's east. Against the backdrop of protracted conflicts brought by both domestic and foreign-backed groups, and littered with indiscipline and violence by members of the national army, Bosco's story is powerfully emblematic of the impunity warlords and members of Congo's national army enjoy - while they profit from the minerals trade at the expense of local communities.

The bottom line: the men with guns continue to get away with it.

Recent Global Witness research shows how Congolese officers sell minerals and profit from mining sites, most commonly by imposing taxes on the poorest artisanal miners. At a gold mine in Kamituga, South Kivu, diggers told Global Witness that the army taxes up to $50 per pit, per week. The single mine we visited had over 60 pits, which means the tax could equate to $12,000 a month for officers. In Bukavu, South Kivu, we witnessed an army Colonel trying to illegally sell minerals at a gold trading house. Until the Congolese government cracks down on them, criminals will continue to manipulate the mineral trade to line their own pockets.

The good news is that international attention is now being paid to Congo's mineral supply chains. Spurred in part by a U.S. law, supply chain due diligence is becoming an international norm for companies sourcing minerals from eastern Congo and other conflict and high-risk areas.

But while some parts of the private sector are slowly shifting in a more responsible direction, the Congolese government is doing little to crack down on its own officers found to be illegally involved in mineral trading. Despite public commitments at an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development forum last year, no senior soldiers have as yet been held to account for illegal involvement in the minerals sector.

Bosco was a kingpin: his arrest has helped to dismantle institutionalised mineral smuggling routes into Rwanda. But other corrupt officers in the army continue to facilitate smuggling and taxation through new, more diffuse networks.

If the Congolese government is serious about reforming a minerals trade that has contributed to financing abusive soldiers and rebels, it must punish the soldiers illegally profiting from it. It must make sure that Bosco's trial marks the beginning of a new way of accountability - including in the minerals sector. Only then can the hopes of the Congolese population for the beginning of the end of their long suffering be met.