Past Global Witness exposés have shown how some Vietnamese companies operating abroad have been disregarding human rights and causing brutal environmental destruction, which they have done at the expense of both their reputation and profits. The re-write of Vietnam’s 2005 Investment Law this year presents an opportunity for remedying this, by setting stricter ground rules for how Vietnamese companies operate outside their own jurisdiction.

Vietnam is a key economic player in the region – with major investment in neighbouring Cambodia and Laos, for example. But in the absence of an adequate legal and regulatory framework this policy of expanding investment overseas carries significant risk.

Two of Vietnam’s most prominent rubber companies Hoang Anh Gia Lai (HAGL) and Vietnam Rubber Group (VRG) are cases in point. HAGL was one of two Vietnamese companies that Global Witness exposed last year for a range of environmental and human rights abuses in our report Rubber Barons. Within 48 hours of the publication of our report publicly listed HAGL’s share prices dropped by 6 per cent, attributed by some media outlets to our exposé. The company has since experienced consistent pressure from investors to bring its operations in line with the law, work with communities to solve disputes and settle compensation claims, and publicly disclose details of its concessions.Some investors withdrew their funds from HAGL altogether due to the associated risks with the company. By February 2014, communities affected by HAGL’s operations in Cambodia had submitted a complaintagainst the company to the International Finance Corporation, which invests in HAGL through a Vietnamese equity fund.

Like HAGL, the rubber plantations of state-owned VRG had systematically ignored legal protections in Cambodia and Laos. Following our exposé, the company has taken a number of steps to address these concerns, including developing a community consultation process in selected plantations. Nonetheless, in December 2013, VRG had its certification under the Forest Stewardship Council suspended, thus limiting its access to a number of markets.

The stakes are significantly higher than they were in 2005, when Vietnam’s Investment law was last written. The country’s foreign direct investment in Cambodia grew more than five-fold between 2000 and 2010, and by 2011 accounted for 71% of ASEAN’s US$880 million investments in the country. According to media reports, Vietnam is also Laos’ largest investor, pouring approximately US$3.5 billion into projects – from land and real estate to manufacturing sectors.

Significantly, Cambodia and Laos also suffer weak rule of law and governance, increasing the need for investors like Vietnam to hold a magnifying glass to their operations there. Beyond potential financial losses for companies, Vietnam’s government risks damaging its own reputation by promoting overseas investment strategies that enable social and environmental harm.

Vietnam is by no means alone here, and could seek inspiration from a number of governments who have already acted to shield their companies from such risk beyond their own borders.

China, for example, issued a series of Guidelines for Environmental Protection in Foreign Investment and Cooperation in February 2013, which aim “to identify and pre-empt environmental risks in a timely manner, lead our companies to actively fulfil their social responsibility in environmental protection, build a good foreign image of Chinese companies and support the sustainable development of host countries”. One year earlier, the country’s Banking Regulatory Commission updated its Green Credit Guidelines, stipulating that banks should align with international standards to strengthen their environmental and social risk management within overseas investments.

Both the USA and UK recently introduced legislation placing requirements on their companies aimed at ending corruption, which apply to all projects, regardless of the country of operation. Meanwhile, in March 2012 the European Union’s Timber Regulations came into force, aimed at blocking the importation of illegally sourced timber into Europe. Vietnam is one of a number of countries negotiating a timber export agreement with the EU, under these new conditions.

In this spirit, Vietnam’s Investment Law should seek to ensure that companies:

a) Observe host country laws and regulations concerning environmental and social protection

b) Respect the cultural heritage of local communities, undertake consultations and share key project information with potentially affected people, in accordance with the international standard of free, prior and informed consent.

c) Undertake rigorous environmental and social impact assessments prior to contracts being secured and cancel projects where potential negative impacts are found to be too great

d) Carry out due diligence with potential local partners, to evaluate their track record for environmental and social protections, and corruption.

A continuation of Vietnam’s “business as usual” approach, on the other hand, could have increasingly negative consequences, not only for local people and the environment but also for “brand Vietnam” abroad.

This blog is based on an article published this week in Vietnam’s leading Vietnamese language business weekly Nhip Cao Dau Tu.

Megan Macinnes is the Head of the Global Witness Land Campaign.

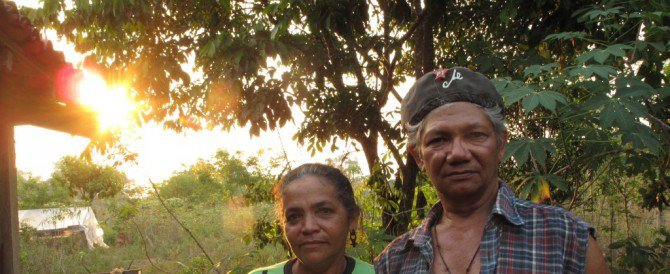

Photo: Flickr, Richard Allway