The UK has just been rapped on the knuckles for failing to do enough to tackle corruption through its development work around the world, in a report from the UK’s official Independent Commission on Aid Effectiveness (ICAI). Afghanistan – languishing right at the bottom of the league table for corruption – is an obvious place to make amends.

The Commission’s first two recommendations are for the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) to set out an overall strategy for tackling corruption, and detailed plans for each country. There, at least, DFID has a head start in Afghanistan: the department produced an anti-corruption strategy back in January 2013.

The existence of the strategy is good news: it may only be three pages long, but it is at least constitutes a recognition of the way that corruption cuts across the whole development agenda – deeply undermining efforts to improve education, health and the economy.

The critical impact of corruption is ignored or at least deeply under-estimated far too often. The US, for example, has yet to develop a cross-cutting anti-corruption strategy – a particularly glaring omission given the billions they are spending in aid.

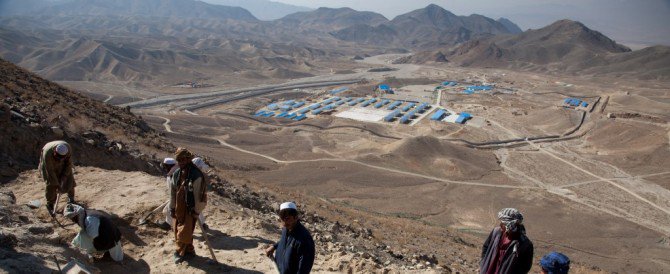

The second piece of good news is that DFID recognises the importance of natural resource management within the strategy. Specifically, the strategy talks about “[e]xpanding support to the Afghan mining and extractives sector to strengthen its systems, reduce opportunities for corruption and enhance opportunities for investment.”

And finally, the strategy recognises the importance of helping Afghans to fight against corruption themselves – a route which may be more effective than outside pressure, and is certainly less vulnerable to accusations of interference. There is even a mention of supporting clean elections – particularly welcome given the way the fraud in the 2014 presidential polls threatened at one point to drive the country to civil war.

So where can they do better?

Whatever the strategy says on paper, there is still little sense that fighting corruption is seen as a really urgent strategic goal. A good example is the 2014 Mining Law. Given the horrifically clear precedents from other countries that have suffered from the ‘resource curse’, persuading the Afghan government to incorporate the strongest possible protections against conflict and corruption should have been a first-order priority. Instead these measures were an afterthought. To be sure, that still makes DFID better than most countries, but it is not good enough.

The Commission’s report says DFID’s “willingness to engage in programming that explicitly tackles corruption is often constrained by political sensitivity.” That much is clear from the fact that over the past thirteen years, it is hard to find more than a tiny handful of occasions where money was actually pulled from aid programmes as a direct result of high corruption levels in Afghanistan.

Conditionality is rightly approached with some caution by donors, but holding the government to its promises on governance is more than just legitimate – anything else would be a dereliction of duty to UK taxpayers. Done right, agreeing benchmarks and incentives for stronger accountability – rather than simply cutting aid after corruption has happened – could encourage effective reforms and avoid accusations that Afghan sovereignty is being undermined.

If there is one problem with the ICAI report, it is that it only looks at DFID. Corruption and weak rule of law are not just development issues: they have a huge impact on stability and security. The recent election in Afghanistan is only the most visible evidence of that. Transparency and governance are especially critical if Afghanistan’s huge reserves of natural resources are to actually provide any benefit for the country: on present form, there is a major risk that they will instead be a source of conflict and corruption.

Efforts to counter this risk should be a core security, economic and political concern for the UK, rather than an optional extra: rather than just being part of DFID’s aid programme, they should be at integrated into the heart of the UK’s overall objectives in Afghanistan and a priority that cuts across government departments.

And that is all the more true for the other major donors. The US military, in particular, spends far more in Afghanistan, and has a far greater impact on policy, than any civilian aid programme. Until they start to see governance as something which affects them directly, which has implications not just for Afghanistan but for their own security, it is unlikely that the international community will be able to use what influence it has to good effect.

And if that means there is no progress on the political and governance problems Afghanistan faces, then stability, as well as development in the country, is likely to remain a mirage.