President Ashraf Ghani, having recently taken office in the first peaceful transition of power in Afghanistan since the early 20th Century, might be wondering how he is going to face up to his next challenge: to implement his pledge to tackle corruption, to make appointments based on merit, and to strengthen the rule of law. But two pieces of recent news should strengthen his resolve and highlight just how important the natural resource sector will be in this effort.

In September, the Director General of the Afghan Treasury announced that the government was all but broke: without a $537 million bailout it would be unable to pay its bills, including government salaries, within a week.

At the same time, Afghanistan published its third report on Afghan mining revenues, under the Afghan Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). This report, covering March 2011 – March 2012, seeks to reconcile what larger mining companies claim they paid the Afghan government in various taxes and fees against what the Afghan government claims it received.

The report shines a rare light on Afghan mining revenues. The government claimed it earned AFS 4.488 billion, or $102m–representing just over five percent of the reported Afghan budget of $2bn.

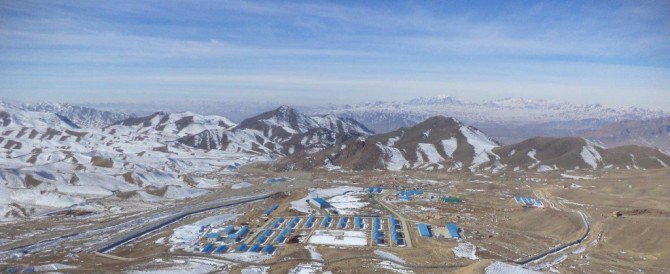

$102m in such a poor country is a useful amount. But look closer, and a worrying picture emerges; only a fraction comes from sustainable sources. The largest seven companies represented 99.17% of total payments made by natural resource companies to the government. Over half of the money came from mostly one-off “premiums and bonuses” for mining projects. Nearly all of that came from one project: the Aynak Copper mine, whose contract is under renegotiation.

Long term sustainable funds from royalties came to a mere AFS 69m ($1.5m) and customs revenues from imports, exports, and other taxes were only AFS 23m (S489,264). This is in spite of the fact that Afghanistan is estimated to sit on almost $1 trillion in mineral wealth, plus substantial oil and natural gas reserves. Here is the key issue: the government is reporting a massive budget shortfall, but has failed to bring in the revenue it needs from natural resources.

Corruption plays a big part. The Ministry of Mines and Petroleum has estimated that there are 1400 illegal mines in the country. Afghanistan has been a major source of precious and semi-precious stones such as emeralds, lapis lazuli, and rubies for 7000 years. But experts estimate that 90 – 95 percent of those stones are immediately smuggled out of Afghanistan today, meaning almost no revenue makes it into the Afghan Treasury.

Those very same resources are funding the conflicts that help make Afghanistan the seventh most failed state in the world. This May, for example, the UN reported that, after opium, illegal marble mines are the second biggest source of finance for the Taliban in Helmand Province. Reports have identified Afghan Local Police commanders smuggling chromite, while the Haqqani network taxes the shipments once they reach Pakistan.

But the Afghan government – and many of its international backers – have so far failed to tackle this problem. This summer, during the height of the election crisis, Afghanistan quietly passed a new minerals law that failed to meet many international standards on accountability, transparency, and security . These measures should have been the first line of defense against corruption.

This issue goes beyond mining, of course. The Ministry of Finance has blamed the current shortfall on the election crisis that deeply spooked business and investors, but budget revenues actually began to fall well before the crisis began in April. In particular, customs revenue, which is about half of the $2bn of the Afghan budget not derived from foreign aid, has long been declining. American officials and the Afghan Customs Department have estimated that customs revenues could double if corruption were alleviated, more than filling the current $500m budget hole.

Weak governance and weak budgets are interrelated problems that have been festering for years, and cut backs in foreign aid are now bringing the crisis to a head. The international community is just beginning to recognize that despite $100bn in American assistance alone, there is still no sustainable economy in Afghanistan to replace foreign aid.

But the Afghan government and the international community have the power to set Afghanistan on a better path. They can prioritize the establishment of a solid regulatory framework for the extractives industry. Reforming the newly passed mining law could take years, but President Ghani could work with the World Bank, civil society, and industry to make sure new regulations help fill the legal gaps and are enforced.

The new Afghan President could also order the Finance and Mining Ministries to move as quickly as possible to meet the new 2013 EITI standards. And he could go beyond the bare minimum, by publishing not just minerals contracts but details of their real, beneficial owners, requiring supply chain due diligence, ensuring Afghan natural resource revenues are audited to international standards, and by encouraging civil society and industry to fully participate in the process. The international community can support this by helping to build capacity and encourage enforcement.

Ultimately, a country sitting on over a trillion dollars in natural resources, plus a very lively artisan and small scale mining industry, should not have to ask for emergency handouts. The only way Afghanistan will be able to stand on its own two feet is if its government, with support from the international community, becomes serious about putting in place the controls needed so it can use the country’s natural resource assets to its own benefit.