The UN's COP30 climate summit in Belém, Brazil will take place in the Amazon rainforest, where it will focus on turning words into action, with an urgent push for climate adaptation, renewed NDCs and plans to unlock $1.3 trillion of climate finance

What is COP?

COP stands for “Conference of the Parties", which is a generic phrase in international relations-speak meaning a committee created after an international treaty is signed, tasked with making decisions about how that treaty is implemented.

There are all kinds of COPs for various international agreements, from chemical weapons to combatting desertification.

But the term COP has come to be associated with the meetings of one particular committee: that created after the signing of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

A total of 154 countries signed the UNFCCC in June 1992, agreeing to combat harmful human impacts on the climate.

Since then, COP meetings have been held (almost) annually to discuss how exactly that should be achieved and monitor what progress has been made.

Each COP is usually referred to by its number in the series, e.g. COP26 was the 26th COP meeting.

Each year a different country becomes the COP president, in charge of organising and running that year’s meeting. Usually this means that the host city moves each year, too.

New agreements that are made at COP tend to be named after the host city, e.g. the 2015 Paris Agreement or the 2021 Glasgow Climate Pact.

Some of these agreements have faced significant headwinds of late. In January 2025 – shortly after his inauguration – President Trump formally began the process of withdrawing the US from the Paris Agreement for a second time, putting the country officially outside the pact by early 2026.

This move places the US – one of the world’s largest emitters – back among a handful of nations outside the accord, casting a long shadow over the future of global climate negotiations.

Who is involved in COP?

We often hear about politicians, diplomats and national government representatives being invited to COP, but they are far from the only ones who attend the conference. Many others join, aiming to influence the outcome – some to push forward climate action and justice, others to advance their own interests.

For example, many fossil fuel lobbyists join the talks to attempt to disrupt negotiations from pledging much-needed action to keep coal, oil and gas in the ground.

At COP27, we found that there were twice as many fossil fuel lobbyists as delegates from the official UN constituency for Indigenous Peoples.

At COP28 in Dubai, we found a record number of industry lobbyists, with nearly 2,500 descending on the talks.

And last year, at Baku’s COP29, more fossil fuel lobbyists registered to attend than all the delegates for the 10 most climate-vulnerable countries.

How do corporations influence decisions on climate action?

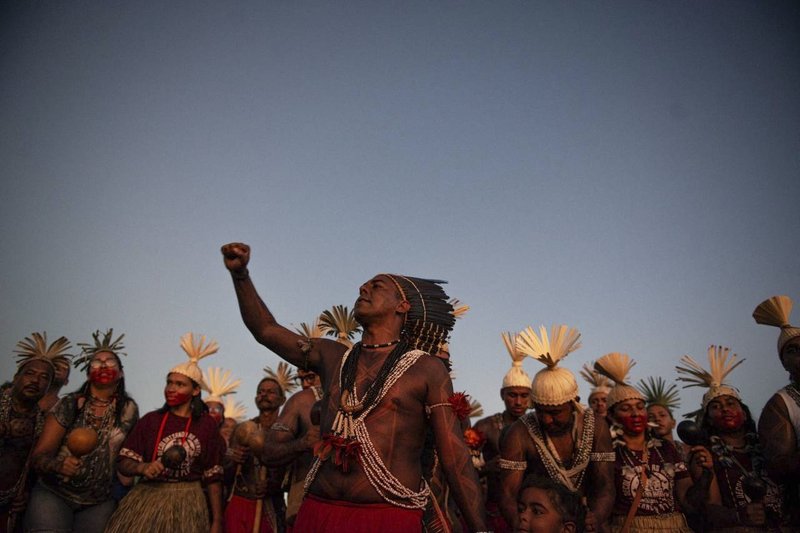

On the opposing side, there are land and environmental defenders, including Indigenous Peoples, calling for greater protections for their territories against exploitation by environmentally destructive industries such as logging, mining and industrial agribusiness.

Climate organisations such as Global Witness attend with partners to advocate for rapid and ambitious action to tackle the climate crisis, while ensuring a just transition.

However, there are often barriers in place – regulatory, economic, legal and physical – that prevent land and environmental defenders, activists and civil society organisations from meaningfully participating in these global decision-making processes.

Unfortunately, those most affected by climate emergency are not the ones who participate directly in negotiations at the conference.

What was agreed at COP29 last year?

In spite of some glimmers of climate action, decisions made at the COP29 summit proved to be lukewarm compared to its predecessors.

First, the good news. Two years on from COP27’s groundbreaking agreement to create a devoted loss and damage fund, negotiators agreed to make the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage operational from 2025.

That consensus brought us one step closer to a working money pot that will award funding to the communities most affected by climate change, but that are least financially equipped to pay for mitigation measures and emergency responses.

As of April 2025, the fund’s board have agreed to begin distributing an initial $250 million to projects at its next meeting.

The climate summit also confirmed a “new collective quantified goal for climate finance” (NCQG) – although negotiators remain split over the target’s finer details.

While developing countries overwhelmingly called for $1.3 trillion every year – which would help to fund their part in the energy transition, as well as build climate resilience – developed nations only agreed to cover $300 billion of that total.

That read as a denial of accountability from those very countries that have cumulatively released the most planet-wrecking carbon emissions (and gained economic dominance off the back of those harms e.g. as the UK did during the Industrial Revolution).

And while 2023 appeared to mark a watershed moment for the fossil fuel industry, with COP28’s final text affirming the need to “transition away” from fossil fuels, COP29’s lack of movement on the issue led to accusations of “backsliding”.

Furious lobbying from oil-rich petrostates obstructed efforts to renew calls to phase out fossil fuels. While one draft text did include a “reaffirmation” of COP28’s agreement, the language remained vague and non-committal.

It will be up to the UNFCCC to kick big polluters out of COP, reject fossil fuel interference and inject new momentum into the summit’s work to reverse the climate emergency.

What will be discussed at COP30 this year?

Dubbed the “forest COP”, COP30 will be the first time that the climate summit takes place in the Amazon rainforest – a fitting venue for what Brazil has said will be the year that both urgency and action will be emphasised.

After years marked by slow progress, the COP30 presidency’s rhetoric calls time on hedging and hand-wringing at the climate summit.

This moment has not arrived too soon. COP30 comes, in the summit president André Aranha Corrêa do Lago’s words, at the “epicenter of the climate crisis,” in a year that follows the first time global heating surpassed the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C threshold.

Brazil’s presidency has named several priorities focused around mobilising climate action and meeting climate finance goals:

- A renewed focus on ending forest loss: At COP26, over 140 countries promised to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030, a pledge reaffirmed at COP28. But despite gains in the Brazilian Amazon under Lula’s government, global forest loss hit record highs in 2024, and we are veering dangerously off-course. Lasting change requires stronger laws to protect forest defenders, enable deforestation-free trade, and an end to the finance driving forest destruction. Against this backdrop, Brazil plans to launch the Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF) at COP30, a proposed $125 billion fund that would invest money in global markets and use the profits to pay tropical forest countries that protect their forests. But this new facility risks papering over the bigger issue: the vast private finance still flowing to deforesting companies. If leaders are serious about saving forests, they must ensure that the TFFF supports Indigenous and local communities directly and sets a new standard for deforestation-free finance, ideally starting with regulations that govern the whole system, not just the fund.

- Baku to Belem Roadmap to 1.3T: UN climate chief Simon Stiell has called this roadmap a “how-to guide” on raising climate finance, which will lay out concrete steps to meet the NCQG’s total $1.3 trillion goal. Ways to raise money – on top of contributions from developed countries – could include private and philanthropic investment, levies on polluting industries, and reforms of multilateral development banks (such as the World Bank and the IMF) to allow them to buy existing private loans for energy transition projects in low-income countries. Plans for the roadmap were shared at Bonn, with updates due to be discussed at COP30.

- Updated National Determined Contributions (NDCs): Crucial to staying within the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C global heating threshold are each country’s individual plans to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, known as NDCs. Every five years, countries must submit revised NDCs to the UNFCCC secretariat, adapting their projected targets and actions to the evolving climate emergency. The third round of NDCs were due in February 2025, but so far only 20 out of 195 parties have submitted theirs. COP30 CEO Ana Toni has optimistically said that these delays could indicate a more thorough stocktake of NDCs and practical plans for their implementation. Whatever the reason, talks at COP30 will look to ease “bottlenecks.”

- Turning negotiations into action: Thirty years of climate negotiations in, and following last year’s criticisms from leading UN climate voices that COP is “no longer fit for purpose”, COP30 president do Lago is calling for a new era of “climate urgency” that moves COP into a “post-negotiation” phase. The tone he hopes to set is less about debate and more about actionable plans. But with multiple petrostates throwing obstacles in the path towards banning fossil fuels at recent COPs, just how far negotiators can push the final text remains to be seen.

Brazil's proposed TFFF would invest money in global markets and use the profits to pay tropical forest countries that protect their forests. Global Witness

What are the contentious issues at this year’s COP?

Brazil’s calls for a “post-negotiation” era – hastened by the very real effects that the climate crisis is having on people across the world – will hinge on whether countries can overcome their sticking points and put dialogue into action.

The fossil fuel industry’s influence over COP’s proceedings – both through oil-rich countries’ reluctance to give up their polluting wealth generator and the thousands of lobbyists that have historically registered for the conference – will also need undoing. But recent shifts in the political climate could shrink any existing appetite to do so.

Who should pay (and how much)?

One debate that has carried over from COP29 into COP30 is precisely how the rest of the $1.3 trillion climate finance goal should be raised – and who is expected to pay for it.

Many developing countries are determined that developed countries should shoulder the bulk of this financing, given that high-income countries like the US and the UK have cumulatively produced the most greenhouse gas emissions since pre-industrial times.

Though developed nations did concede to supplying at least $300 billion at COP29, there is still disagreement over how much of the total will come from developed nations’ public money.

While the EU’s representative at Bonn told Climate Home News that private investment should be mobilised more, a delegate from Independent Alliance of Latin America and the Caribbean (AILAC) urged that private and philanthropic sources should not offset developed nations’ obligations to the NCQG.

India has also said that it opposes global tax levies and attempts to raise money from specific sectors, which could preclude levies on polluting industries like air travel.

The issue of debt was also raised at Bonn. Last year, a report by the International Institute for Environment and Development found that over half of climate finance distributed in 2022 was based on loans (i.e. debt) rather than grants.

Climate finance must not push climate-vulnerable nations already saddled with massive debt-burdens further into arrears.

At Baku’s COP29, more fossil fuel lobbyists registered to attend than all the delegates for the 10 most climate-vulnerable countries

Fossil fuel influence

If we are to truly enter an era defined by “climate urgency”, this must be the year that fossil fuel lobbyists’ grip on COP is finally shaken off.

Last year, an undercover Global Witness investigation showed that the CEO of COP29 was willing to facilitate talks about fossil fuel deals for an undercover investigator.

And in its year as COP28 host, our calculations show that that the UAE’s state-owned fossil fuel company pursued close to $100 billion worth of oil and gas deals.

Add to that the hordes of fossil fuel lobbyists that register to attend the climate summit each year (which at COP29, in collaboration with Kick Big Polluters Out, we put at 1,773), and it’s clear that COP cannot take serious action against planet-wrecking greenhouse gas emissions until it clears out its own house.

The Belém presidency’s rhetoric sounds positive, but its own country’s track record could be its undoing. Brazil is one of the top 10 oil producers in the world, coming in ninth in 2024.

Rather than scaling back its fossil fuel industry dominance, Brazil’s oil and gas production is set to expand by 20% by 2030, largely driven by its state-owned fossil fuel company Petrobras.

The government also recently granted new licenses for oil exploration in the Amazon region. This controversial move has sparked criticism from its own Environment Minister, as drilling in such ecologically sensitive areas poses severe risks to biodiversity, Indigenous communities and the global climate.

NDCs and political will

All countries must be persuaded to submit ambitious and inclusive NDCs that show their renewed commitment to combatting the climate crisis. Worryingly, if the ongoing widespread rise of climate sceptic right-wing political parties is anything to go by, we may find ourselves up against severely reduced political ambition at this crucial moment.

In the EU, we have been campaigning against attempts to undermine a hard-won anti-deforestation law that could help to save 8 million hectares of forest and prevent 2+ billion tonnes of CO2 emissions in its first decade.

And in the US, Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement is likely to put on pause the US’s contributions to international climate finance, making the $1.3 trillion goal even more difficult to reach.

There is a risk that the US’s departure from the Paris Agreement might encourage a domino effect across the globe, where countries increasingly renege on their climate adaptation and mitigation measures, particularly their NDC submissions.

In the face of this retreat from critical measures to combat the climate crisis, campaigners will need to be more vigilant than ever at this year’s climate summit.

People in, polluters out

COP30’s presidency has highlighted the Indigenous concept of “mutirão” (“Motirõ” in Tupi-Guarani language) – meaning a community coming together on a shared task – as a central ethos for the conference. We’ll be watching closely to see how fully Indigenous Peoples’ and frontline community voices are integrated into this year’s “mutirão”.

We’ve been partnering with Indigenous Peoples and land and environmental defenders across the globe for the past year to call for those most affected by the climate crisis to be given a central role in climate negotiations.

As communities with an intimate knowledge and lived experience of our natural world, and as those who are frequently impacted first by environmentally destructive extractive industries, it is these people’s expertise that we should pay heed to most.

Encouragingly, the COP30 presidency launched the Indigenous Peoples Circle and the International Indigenous Commission earlier this year, which both signal a desire to incorporate Indigenous voices into the heart of COP.

But as the second most dangerous country in the world for land and environmental defenders, Brazil must show that its climate frontline can be protected beyond COP’s circle.

This year’s COP30 will be a pivotal moment for the climate summit. It could be an opportunity to enact exactly the kind of climate action and climate justice the world needs to see, or another repeated failure of international diplomacy. We hope COP30 seizes the moment.