Artisanal mining gets a lot of bad press. It is often demonised as a sector rife with human rights abuses, child labour and environmental destruction. Companies have sometimes disengaged with artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) suppliers as a kneejerk reaction to calls for more responsible sourcing practices. However, those thinking that this is a solution are labouring under a misapprehension.

While it is undeniable that there are serious problems in artisanal mining which must be addressed, ASM is a huge and diverse sector, which varies widely across mines, local areas and countries. Moreover, supply chain risks are in fact just as prevalent in large-scale mining, but often overlooked. Cutting artisanal miners out of the picture is not the answer to ensuring that metals and minerals are sourced responsibly.

That is why we at Global Witness welcomed the London Metal Exchange (LME)’s inclusion of artisanal mining in its new proposal on how to address responsible sourcing. However, not everyone appeared to receive the move with open arms.

The Financial Times (FT) in particular, reacted to the LME proposal in a piece headlined, LME to allow ‘artisanal’ miners despite child labour concerns,appearing to question the inclusion of artisanal minerals under the responsible minerals policy. While at first glance, the business press may appear a stronger advocate for human rights than a watchdog like Global Witness, this is not the case. The FT’s headline reflects a well-worn misrepresentation of the ASM sector by the mining industry and press and an oversimplification of what true responsible sourcing practices entail.

Artisanal mining is key to livelihoods

ASM is an important source of income in many developing countries with 40 million people working and 150 million depending on ASM across 80 countries in the Global South, which constitutes up to 10% of some countries’ population. Often these workers are among the poorest demographic and mining provides a crucial source of income. With ASM supplying around 25% of global cobalt, tin and tantalum production, its contribution is substantial for certain minerals.

If the mining industry were to turn its back on ASM, it would pose a great threat to a critical source of livelihood in producer countries.

The London Metal Exchange’s (LME) decision to include ASM follows internationally agreed guidance for sourcing minerals responsibly, the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas. It understands ASM as an integral part of mineral supply chains with the potential to provide important benefits to local communities engaged in mining, if carried out responsibly.

Cutting human rights abuses out of supply chains, not artisanal miners

A part of the ASM sector is indeed connected to child labour, other human rights abuses, environmental damage and conflict, and Global Witness and other NGOs have continuously reported on these issues. However, these are complex problems requiring complex solutions, of which a boycott of ASM is not one; a subject on which Global Witness has written extensively. Furthermore, not all mineral production from ASM is related to such problems.

Instead of simply excluding a whole sector, the OECD Due Diligence Guidance takes a different approach by calling upon companies to set-up due diligence policies, monitor their supply chains for risks to human rights and other harms, and take steps to mitigate them. Supply chain due diligence should be about how companies do business, supporting them, where possible, to avoid the potentially catastrophic consequences of withdrawing from local economies. By promoting constructive engagement with suppliers that drives improvement and discourages kneejerk, and potentially damaging, disengagement from areas that are determined to be high risk, supply chain due diligence can contribute to a more responsible sector overall.

Industrial mining isn’t better

If you think that all problems associated with mining are on the artisanal side, think again.

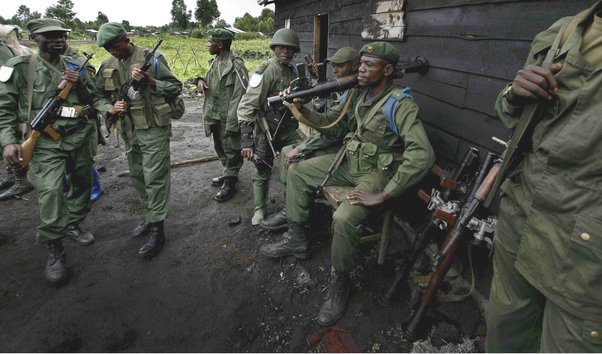

Large-scale mining (LSM) is also linked to many risks, including human rights abuses, environmental degradation and corruption.

Earlier this year we saw how deadly large-scale mining can be. The break of a tailing dam at a Brazilian iron mine owned by mining giant Vale killed over 230 people. Vale is a repeat offender: 3 years before and only 60 miles away, another dam collapsed at a mine owned by a consortium of Vale, BHP and Samarco , killing 19 people, polluting a river and devastating livelihoods.

The security situation around large-scale mining sites is also often dire – there are numerous reported cases of security forces from mining companies or the state using disproportionate force against the population. The Justice and Corporate Accountability Project has documented 44 deaths (30 of which were classified as “targeted”), 403 injuries (363 of which occurred during protests and confrontations), and 15 cases of sexual violence associated with Canadian mining companies in Latin America over a 15-year period.

Numerous cases of environmental destruction and forced evictions relating to large-scale mining projects have been documented. For example, Amnesty International investigated a big copper mine project in central Myanmar, reporting that thousands of people were driven from their homes without adequate compensation or relocation and that hazardous waste discharged from the mines exposed communities to serious health risks.

Corruption is another major issue in large-scale mining. Kofi Annan’s Africa Progress Panel estimated that five suspicious mining deals including, amongst others, Glencore and the Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (ENRC)[1], both companies listed on the London Stock Exchange at that time, lost the Congolese state at least $1.4 billion - twice Congo’s annual spending on health and education combined. The two companies strenuously deny charges of impropriety and both say they have adopted policy guidelines on corruption, bribery and due diligence.

All supply chain risks must be addressed across large and small-scale mining

There are serious risks related to mining, both in the artisanal and the large-scale sectors, including human rights violations, environmental destruction and corruption.

The LME’s decision to launch rules for responsible sourcing is therefore a step in the right direction towards changing company behaviour and sourcing practices, albeit with some significant gaps.

To simply stop doing business with artisanal miners, would have been a regressive and damaging step in the wrong direction. Companies should instead engage responsibly by doing proper due diligence all the way along the supply chain and across both large and small-scale mining.

[1] Since 2013 owned by the Eurasian Resources Group