A joint investigation by Global Witness and the Internet Freedom Foundation shows that YouTube and microblogging site Koo are failing to act on misogynistic hate speech reported on their platforms in India and the US, endangering women and minoritised groups, and enabling a toxic information ecosystem in a critical election year.

Talking the talk, but not walking the walk?

Online hate speech can lead to real-world harms, as seen in the use of Facebook to spur ethnic violence in Myanmar, or the radicalisation of the Christchurch shooter on YouTube. Major tech platforms and many national laws prohibit hate speech and incitement to violence, yet the research of Global Witness and others have shown social media corporations have a terrible track record when it comes to detecting this banned content.

In response to the exposure of harmful content on their platforms, these corporations have pointed to the tool they give users to report such material, allowing it to be reviewed and removed if it violates the company’s policies. But does the reporting process actually work? Our investigation into two platforms reveals startling oversights.

Testing the platforms’ reporting tool

We set out to test the reporting process on two social media platforms, the video sharing site YouTube and the microblogging site Koo, in both India and the US. We decided to conduct our research in these two different geographic contexts because they are both large global democracies with national elections in 2024, where online hate speech and misinformation have already led to offline violence. Assessing the performances of a well-established and popular video platform headquartered in the US and a newer Twitter-like platform based in India gives a useful indication of their preparedness for dealing with prohibited content around the elections.

Evidence suggests the impact of online harassment is heavier for women than men (notably for journalists and politicians), and that online attacks against women are more often based on gender. Given this, we chose to focus on hate speech against women on the basis of sex/gender.

We began by identifying real examples of gendered hate speech content in English and in Hindi that were viewable on the platforms but clearly violated the companies’ hate speech policies. [1] In November 2023 we reported the content and details of the violation using each platform’s reporting tool, totalling 79 videos on YouTube and 23 posts on Koo.

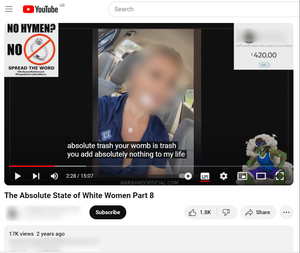

A still from one of the reported YouTube videos in which the narrator reviews the social media accounts of a woman with claims including “this chick is 100 percent worthless, useless... your genes are trash, absolute trash, your womb is trash, you add absolutely nothing to my life...”.

For platforms’ hate speech policies to be effective, their enforcement needs to be timely. However, a full month after we reported the hate speech, the results showed an alarming lack of response from YouTube and inadequate action from Koo. Of the 79 videos reported, YouTube offered no responses beyond an acknowledgement of each report. The status of just one video changed, to include an age requirement for viewers, although it is unclear if this action was undertaken as a result of the reporting. Koo removed just over a quarter of the posts reported, leaving the vast majority live on its site. Both platforms are failing to deal with material they say has no place on their sites, posing serious concerns around the spread of harmful content.

YouTube: Asleep at the switch

YouTube states that videos that “claim that individuals or groups are physically or mentally inferior, deficient, or diseased” based on their sex/gender violate the company’s hate speech policy and are not allowed on the site. It continues, “this includes statements that one group is less than another, calling them less intelligent, less capable, or damaged.” The policy also prohibits the “use of racial, religious, or other slurs and stereotypes that incite or promote hatred based on protected group status”, which includes sex/gender.

In one of the videos a man addresses the camera and says: “By the time a woman is 40 she is completely wrecked. They have no-one to blame but themselves… Women are dogs. Women have the dirty minds. The psyop is that men are dogs. Men are honourable. Men give a shit. We keep women from being whores. A good man keeps a woman from being a whore. On their own, without a man, without being subject to the love of a man, all women become whores.” This amounts to a claim of inferiority.

A still from a reported YouTube video titled “Feminist are not women and therefore don’t deserve our love or respect”, in which the narrator claims that “there is a great evil that lies within women that will destroy your nation weaken men”.

In another, a male narrator names a woman and shows clips from a video she has posted on social media. He says, “Realise this chick is over 30. This chick has had sex with over 100 guys, this chick is 100 percent worthless, useless. Your genes are - your genes are trash, absolute trash, your womb is trash, you add absolutely nothing to my life but you bend over on Instagram and a couple million likes from some thirsty Indian dudes so you think you still got it. You don’t. You’re old.” These statements assert the woman is inferior and damaged.

Like other tech platforms, the company tells users to report such material, and it will be reviewed and removed if it violates the company’s policies. Yet when we reported 79 videos containing misogynistic hate speech in India and the US, the platform did not remove any of them. The status of only one video changed, a Hindi-language video to which an age restriction was added, but it is unclear whether this resulted from the reporting process. (The restriction requires viewers to sign in to demonstrate they are 18 years old in order to watch.)

YouTube says it “reviews reported videos 24 hours a day, 7 days a week”, but a month later there was little evidence of any review having taken place. After over a month, all the videos remained live on the platform.

Koo’s mixed record

Similarly, Indian microblogging platform Koo (similar to X/Twitter in its design) also failed to act on most of the content violating its policies that we reported. Out of 23 posts we reported, including misogynistic attacks against female politicians, the platform removed six, or just over a quarter.

Screenshot of a reported Koo post in India containing hate speech towards a prominent Indian female politician, calling her a female dog, changing her name Mamta to Mumtaz (a Muslim name) and telling her to “go to Bangladesh, now you will die”.

Koo states in its community guidelines on hate speech and discrimination that “we do not allow any content that is hateful, contains personal attacks and ad hominem speech. Any form of discourteous, impolite, rude statements made to express disagreement that are intended to harm another user or induce them mental stress or suffering is prohibited.” It continues, “examples of hateful or discriminatory speech include comments which encourage violence… attempts to disparage anyone based on their nationality; sex/gender; sexual orientation…”

One of the reported posts abused a leading female journalist, accused her of spreading communal hatred, and even referred to a Muslim woman in a theatre being “lucky to walk out alive”. Despite being reported on grounds of promoting hate speech, Koo didn’t take any action after reviewing it. Another post that used slurs like “Hardcore Jihadan Terrorist” to describe a famous Indian female journalist did not get removed or taken down by Koo. In another the author dehumanises a public figure, calling her a “goat” and casting aspersions on her pregnancy.

In contrast to YouTube, Koo was quicker to respond to reported content, completing its review process within a day for the majority of posts. It issued notifications in the app to acknowledge the review and removal of six of the 23 posts reported, and that it had reviewed and taken no action on 15 others. However, it failed to provide any response for two of the posts. While YouTube and Koo operate at very different scales with different content forms, Koo’s relative responsiveness suggests a more functional reporting mechanism.

Follow the money

Most social media corporations design their platforms to collect information on users to target them with advertisements, and to keep their attention in order to sell more ads and therefore make more money. This profit-driven business model favours expressions of outrage and extreme content as this has been shown to get more engagement.

But pushing such content has serious consequences, notably hate crimes and attacks against minorities.

High stakes ahead of elections

In a year in which India, the US, and over sixty other countries will hold national elections, social media companies’ failures to deal with prohibited content also poses a threat to election integrity.

A bonfire of harassment and attacks against public officials and election workers in the US, kindled on social media, has led workers to resign and may cause the disruption of democratic processes.

Interference campaigns seeking to disenfranchise voters, spread disinformation about candidates, or polarise voters on ethnic or religious lines are another pressing danger. In Italy’s 2022 election, research by Reset documented lax content moderation processes by major social media companies exposing voters to hate and disinformation.

As it becomes easier to create convincing synthetic content, such as deep fakes and AI-generated text, platforms must be prepared for a new level of information operations and improve their detection and review of prohibited material. These developments cannot be met with an over-reliance on automated content moderation systems, shown to be prone to errors, particularly in low-resource languages (which have little or poor quality material to train automated systems on), while the platforms have long prioritised their content moderation work in English over other languages.

Conclusion

The lax responses of YouTube and Koo to the reporting of misogynistic hate speech in this investigation show both platforms are failing to review and act on dangerous content. Instead of generating revenue from hate, social media platforms should uphold policies designed to protect the safety of their users, and spaces for civic discourse and democratic engagement more broadly. The same applies for the topic of climate change, where YouTube has been found to run ads on some climate denial content despite policies against doing so. Their current practices are demonstrably inadequate, and leave the door open for hate and disinformation. In a major election year, social media corporations must learn from previous mistakes and properly resource content moderation, stop monetising hate, and disincentivise polarising content.

In response to Global Witness and Internet Freedom Foundation’s investigation, a Koo spokesperson said the company is committed to making the platform safe for users and endeavours to keep developing systems and processes to detect and remove harmful content. They said it conducts an initial screening of content using an automated process which identifies problematic content and reduces its visibility. They said subsequently reported content is evaluated by a manual review team to determine if deletion is warranted, following several guiding principles. [2]

Google was approached for comment but did not respond.

[1] The identification phase included the use of a “slur list” that was created as a part of the Uli project.

[2] Koo’s full response was: “Each Koo undergoes initial screening using our automated algorithm, which identifies potentially problematic content. Content flagged by the algorithm has its visibility reduced, meaning it is excluded from trending topics and hashtags but remains accessible only to the Koo account's followers. This step is crucial in preventing the dissemination of potentially harmful content, particularly in cases where content borders on hate speech and resides within a contentious gray area.

Subsequently, reported Koos are further evaluated by our manual review team to determine if deletion is warranted. We adhere to several guiding principles when evaluating reported Koos:

A. Koos that do not target individuals and do not contain explicit profanity are typically not deleted.

B. Koos reacting to public controversies without explicit profanity are generally retained.

C. Our decision not to delete such Koos does not constitute an endorsement; rather, it reflects our commitment to moderation. In addition to automated visibility reduction, we implement account-level actions, such as blacklisting, for accounts exhibiting repeated problematic behavior. Blacklisting entails hiding all future Koos from the account by default and rendering the profile undiscoverable to users outside its follower network.

While moderation is an ongoing journey, our endeavor is to keep developing new systems and processes to proactively detect and remove harmful content from the platform and restrict the spread of viral misinformation. We are committed to making Koo a safe platform for our users and appreciate your cooperation in maintaining a safe and respectful community on our platform.”

[3] You can find further examples of the content of the videos and posts we reported here.

Credit for listing image illustration: Nate Kitch / Global Witness

- Letting hate flourish: Download the report as a PDF (1.7 MB), pdf