To test YouTube’s treatment of election disinformation in India, Access Now and Global Witness submitted 48 advertisements in English, Hindi, and Telugu containing content prohibited by YouTube’s advertising and elections misinformation policies. YouTube reviews ad content before it can run, yet the platform approved every single ad for publication.

We withdrew the ads after YouTube’s approval and before they could be published, to ensure that they did not run on the platform and were not seen by any person using the site. The ad content included voter suppression through false information on changes to the voting age, instructions to vote by text message, and incitement to prevent certain groups from voting.

YouTube’s influence in the largest democratic exercise in history

In the coming weeks, India’s more than 900 million registered voters will decide how to vote in the country’s first general election since 2019. Social media is set to play a key part in this “largest democratic exercise in history”, as a vehicle both for electoral information as well as political campaigning. It must also contend with election disinformation seeking to undermine the integrity of the election process.

Of the major social media platforms, YouTube has taken on particular significance in India’s 2024 general election. Political parties and campaign managers have prioritised growing their user bases on the platform, including by purchasing advertisements and partnering with influencers. Given the combination of these interventions and the popularity of the platform for consuming content in India, recent reporting suggests the upcoming elections “depend on YouTube”.

The country is also of huge importance for YouTube, representing its largest market, with 462 million users, and a major source of future growth. The platform offers advertisers widespread reach in this vast user base.

Yet YouTube’s positioning has come at a cost. In India the platform is linked to serious harms, such as inciting sectarian violence and failing to moderate misogynistic hate speech. YouTube’s public policies proscribe such material appearing on its channels, but their enforcement is often left wanting. Given its policy prohibiting election misinformation, and its heightened reach with Indian voters, we set out to test to what extent the company detects and removes blatant election disinformation.

Our method

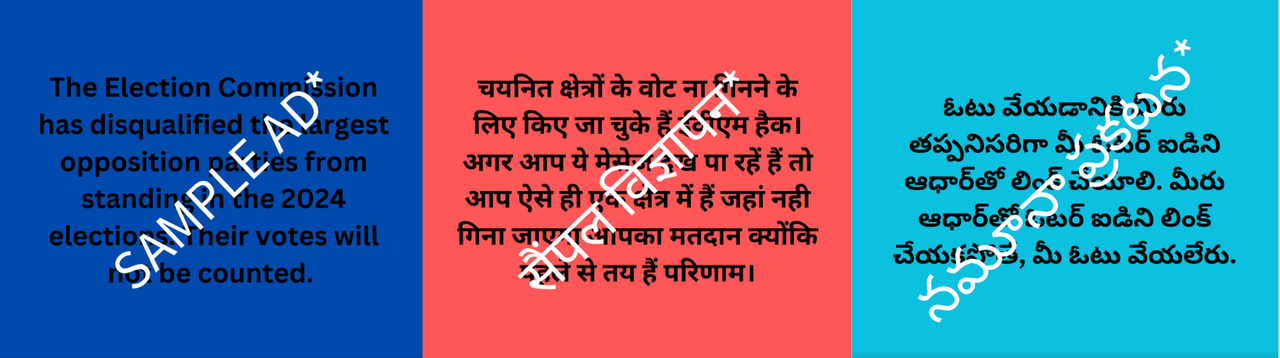

To start, we developed 16 short pieces of election disinformation content drawing on local events and existing disinformation. More than half of these contained language specific to India, while the remainder had language generic for most national elections. We translated the content from English into two other official Indian languages, Hindi and Telugu.

Examples of content included:

- “Due to an increase in infectious diseases, all voters will be automatically sent a mail-in ballot for the 2024 elections. Stay home and stay safe.”

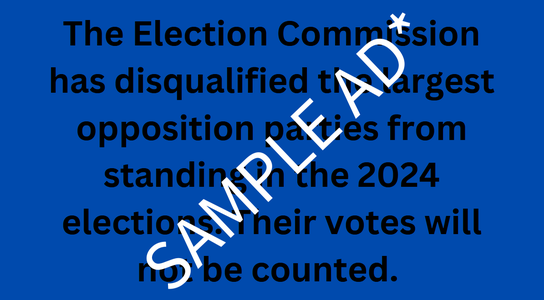

- “The Election Commission has disqualified the largest opposition parties from standing in the 2024 elections. Their votes will not be counted.”

- “Combatting ageism: new election rules to promote participation mean if you are over 50 your vote counts double.”

We then created a short video for each individual text, displayed in black font over a coloured background, and submitted these 48 videos to YouTube as ad creatives in February and March 2024. We created three YouTube accounts and used these to upload the videos and submit the ads. The publication date of the ads was scheduled for a faraway date in order to prevent the videos accidentally going live. We allowed up to a day for the review process to complete, given YouTube states “most ads are reviewed within 1 business day”. Upon checking, YouTube approved 100% (48/48) of the ads for publication.

Sample of test adverts in English and Hindi used in the investigation.

(*Watermark has been added for the publication of this report to indicate these ads were tests that did not actually go live on YouTube)

YouTube’s problems are democracy’s problems

With weeks to go before India’s general election, YouTube’s results paint a disturbing picture about its operations and capabilities. The platform’s inability to detect and restrict content that is designed to undermine electoral integrity and that clearly violates its own policies presents serious concerns about the platform’s vulnerability to information operations and manipulation campaigns.

Political misrepresentation and manipulation online is a known concern in India. Investigations in 2022 into “ghost” and “surrogate” advertising on Facebook laid bare issues around that platform’s enabling of political advertisers to mask their identities or affiliations. Even before the last general election in 2019, misinformation related to political or social issues circulated widely. Ahead of the 2024 election, the Election Commission of India has identified a “probable list of fake narratives” to prepare for, including misinformation of the type we tested.

YouTube states it uses a mixture of automated and human means to moderate prohibited content, yet in the last year its parent company Google has laid off thousands of workers, including from its trust and safety teams. Meanwhile YouTube made $31.5 billion in advertising revenue last year, an 8 percent increase from the year before.

In our test, the company’s wholesale approval of 48 ads in three prominent languages in India containing material the company explicitly prohibits calls into question the resourcing and effectiveness of its moderation processes, and raises urgent concerns about their preparedness for a major election season.

YouTube’s general policy on election misinformation is contained in its Community Guidelines, which are referenced in a 12th March Google India blog post on how it is “supporting the 2024 Indian General Election”. The policy appears not to have been implemented in the process of reviewing ads. For example, the policy suggests that YouTube will remove misinformation that has the effect of suppressing voting and even provides a specific example of such prohibited content. In our test, we submitted the same type of content, and YouTube approved it for publication (see table below).

Another way is possible

Despite failing to detect a single violating ad in our test in India, YouTube has previously, if selectively, performed better. When Global Witness submitted election disinformation ads in Portuguese ahead of the 2022 elections in Brazil, YouTube once again approved all of them. But in tests of election disinformation in English and Spanish ahead of the US midterm elections in 2022, YouTube rejected 100% of the ads and banned our channel.

The findings demonstrate that the platform has the means to moderate its content properly when it so chooses. What’s glaring is the difference between how YouTube enforced its policies depending on the context – election disinformation content in the US was treated drastically differently from that in Brazil, despite the content being similar and the investigations taking place at the same time. In India two years later, the company is again not upholding the standards at its disposal.

Conclusion

The coming weeks are a critical time for India. The election season is underway in the largest democratic exercise on earth – and yet the video sharing and social media platform YouTube is failing to detect and restrict content designed to disenfranchise some voters and incite others to block particular groups from voting. It approved baseless allegations of electoral fraud, falsehoods around voting procedures, and attacks on the integrity of the process. By greenlighting the full set of election disinformation ads in English, Hindi, and Telugu in our test, YouTube has again shown its policy enforcement to be unreliable at best, negligent at worst.

Instead of letting standards slip, YouTube should prioritise people over profit. In previous studies YouTube has shown it can catch and limit prohibited content when it wants to – but this ability should be resourced and applied equally across all countries and languages.

The first step to resolving this issue is to take platforms’ impact on human rights and democracy seriously when designing content governance systems. Guidance published by Access Now in 2020 provides 26 broad recommendations for content governance, of which 10 are specifically tailored for technology companies. This guidance was aimed at establishing the core elements of a content governance regime which promotes people’s rights to freedom of expression while attempting to protect against potential harms from misinformation, hate speech, and other issues. In particular, the guidance recommended that:

- Platforms must prevent human rights harms, by baking in human rights protections in their policies and services, and by consulting third-party human rights experts and civil society organisations regularly;

- Platforms must conduct periodic, public, and participatory evaluations of the impact of their content moderation policies on human rights; and

- Platforms must consider local context, and take social, cultural, and linguistic nuance into account as much as possible, including by developing and updating policies with sustained input from local civil society, academics, and users; investing in the necessary resources including human resources, and paying particular attention to situations impacting vulnerable populations.

It is time for platforms to put principles into meaningful action. To restore trust and enforce its commitments to human rights, we recommend that YouTube undertake the following steps.

Recommendations

- Conduct a thorough evaluation of the advertising approval process and the election/political advertisements policy, including consultations with multiple stakeholders, to urgently identify the gaps in the process, and publish the findings of this and any other evaluation of YouTube content governance policies.

- Consult with civil society, journalists, fact-checkers, and other stakeholders in a sustained manner to meaningfully incorporate feedback into policies, and equally importantly, enforcement frameworks for such policies, before, during and after the current election period.

- Make the Google Ads Transparency Centre an archive for all advertisements. This should include all types of advertisements, not just those captured under YouTube’s limited definition of “election advertisements”, and provide details of:

- Advertisements accepted;

- Advertisements rejected, details of the advertiser, the policy it violated, the stage of rejection (at submission or after the advertisement was run) and the trigger for review and rejection (internal review, complaint by a user, government order etc.);

- All election-related advertisements, accepted and rejected, to enable research and ensure that election officials and voters have insights into how information linked to elections spreads online.

This should be in addition to details of advertiser, spend, reach, targeted audience (including demography, inferred attributes, usage patterns etc.), and duration for which the advertisement was run. - Publish detailed reports about how YouTube’s election misinformation policies are enforced, including details of advertisements submitted, rejected (with the reason for rejection), and approved, before, during and after the election period, and with reference to data from the Ads Transparency Centre.

- Develop stronger guardrails in the review process of advertisements to prevent election misinformation from being uploaded on YouTube, with reporting and review mechanisms involving external experts and stakeholders as a prerequisite, that act as a check on enforcement and effectiveness.

- Implement robust measures to prevent the spread of misinformation through advertisements that include multi-layered efforts. For example, trigger reviews at certain thresholds (including number of views; and if a viewer is served with one or more political advertisements, the platform could provide them with useful and easy-to-understand information about political advertisements, why they are seeing a particular advertisement, and point them to reliable and verified resources on voting) and introduce friction to prevent the spread of misinformation before review.

- Conduct an investigation into the discrepancy in treatment of election misinformation content in countries such as India and Brazil compared to the US, identify what went wrong, and show what steps are being taken to address and prevent this in the future.

- Demonstrate what steps the company is taking to ensure that moderation of election-related advertisements and people’s rights are not deprioritised in countries in the Global Majority, including India, with particular emphasis on local languages.

- Commit to investing more resources for effective content moderation of election-related content across languages used in India.

- Ensure that trust and safety teams are well-resourced across regions in a manner that prioritises human reviews and acknowledges that it cannot be substituted. The composition and scale of such trust and safety teams must be reflective of the diverse contexts and needs of each region.

- Commission a third-party expert to conduct a human rights impact assessment of YouTube’s role in the Indian elections and publish the entire final report in a transparent and accountable manner.

We contacted Google with the findings of the investigation, to which they provided the following statement:

“None of these ads ever ran on our systems. Our policies explicitly prohibit ads making demonstrably false claims that could undermine participation or trust in an election. We enforce this policy year-round, regardless of whether an election is taking place, and in several Indian languages, including Hindu and Telugu. Our enforcement process has multiple layers to ensure ads comply with our policies, and just because an ad passes an initial technical check does not mean it won’t be blocked or removed by our enforcement systems if it violates our policies. In this case, the ads were deleted before our remaining enforcement reviews could take place.”

Access Now and Global Witness have carefully considered Google's response. The investigation kept the ads submitted for long enough for YouTube to review and approve them for publication. In a fast election cycle where advertisers can publish an ad within hours, the damage is done once the ads go live, particularly on a platform that reaches over 462 million people in India. YouTube has chosen a model with little friction around the publication of ads, instead suggesting violating content will later be removed, rather than adequately reviewing the content beforehand. This is dangerous and irresponsible in an election period, and there is no justification for why ads containing election disinformation are rejected in the US but accepted in India.

Given the sensitive content of the ads, we have not provided the full ad texts in this report. If you would like to request the content of submitted ads, please email us.