A Canadian asset manager part run

by green finance champion Mark Carney cleared thousands of football fields

worth of tropical forest in Brazil, our investigation can reveal.

An estimated 9,000

hectares of deforestation, the legality of which could not be proven by

Brookfield Asset Management, took place on eight farms owned and managed by

Brookfield’s soybean farming empire. The forest clearance took place in the Cerrado, Brazil’s tropical savannah,

between 2012 and 2021, according to analysis of satellite imagery from Brazil’s

space institute, before the properties were sold off in late 2021 in a slash

and sell move. The empire also owned a farm whose managers sought to evict indigenous

peoples from land they claim their own.

Brookfield’s involvement in

deforestation and human rights abuses contrast with its own environmental,

social and governance (ESG) policy and Mr Carney's public image.

“We operate with the highest

ethical standards, conducting our business with integrity,” Brookfield wrote in

its latest annual report. But Brookfield’s owner-operator-investor model means

it could have profited three times from forest destruction in Brazil - from the

sale of commodities, from the sale of financial instruments derived from these

commodities and from fluctuations in the price of its resale assets such as

farms.

Brookfield and its biggest

banking backers HSBC, Deutsche Bank and Bank of America, signed up to the

Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) in April 2021. The alliance commits its signatories

to taking immediate action to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Yet

deforestation on Brookfield farms released an estimated 600,000 tonnes of CO2 in

the nine years to June 2021, destroying parts of a crucial carbon sink and

biodiversity hotspot. In September, GFANZ leaders, including Mr Carney, wrote to members urging them to stop financing deforestation, warning "the world will not reach net zero by 2050 unless we halt and reverse deforestation within a decade" .

At that point, all GFANZ members were required to follow criteria set by the UN's Race to Zero campaign to "ensure credibility and consistency", including achieving deforestation-free supply chains by 2025. However, in late October 2022, GFANZ announced it was no longer mandatory for its members to adhere to Race to Zero targets. This happened shortly before Race to Zero planned to introduce independent monitoring controls with the power to evict non-performing financial institutions from the alliance, raising questions about the willingness of GFANZ members to be held accountable to their pledges.

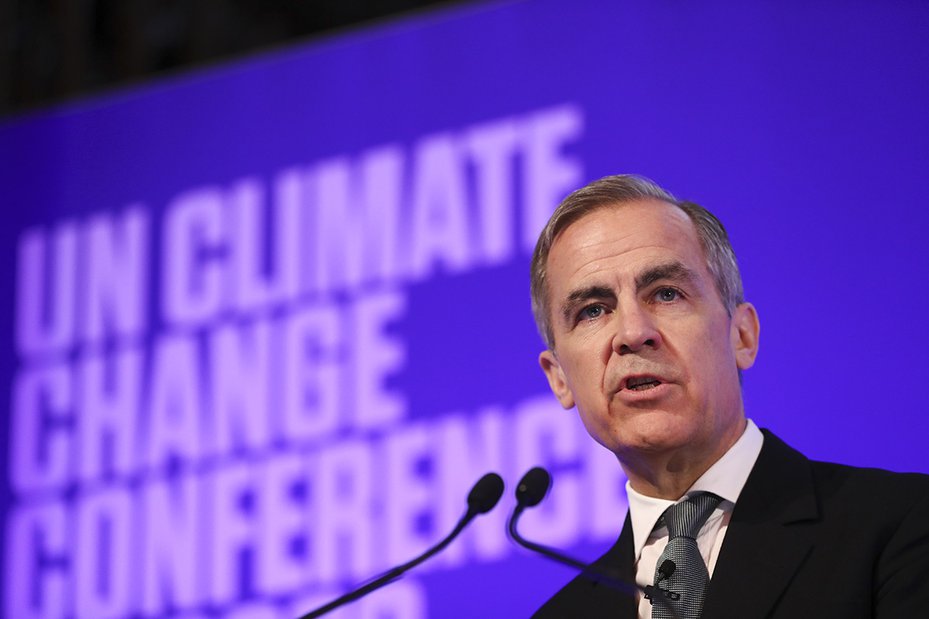

Mark Carney, former governor of the Bank of England, speaks at the launch of the COP26 Private Finance Agenda in 2020 in London, UK. Bloomberg/Getty Images

Mark Carney is one of the founders and public faces of GFANZ, and has been Head of Transition Investing at Brookfield since August 2020. The deforested farms were sold off in 2021 and Carney was promoted from Vice Chair to Chair of the firm in December 2022. Mr Carney was appointed special adviser to then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson for COP26 in January 2020, and he has been a UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance since 2019.

Brookfield faces allegations

of clearing trees from climate-critical forest land to make way for cash crops,

while seeking to evict indigenous people from the heart of the Amazon to make

way for cattle and mining opportunities. A ranch which Brookfield attempted to

sell in January 2022, after the asset was frozen by a local court, battled for

years to evict an endangered indigenous community from their ancestral land.

And in another alleged human rights abuse, a firm controlled by Brookfield was

fined R$800,000 ($163,000) in December 2021 for slave labour offences at a

different farm.

Brookfield’s deforested farms were controlled through a

network of investment funds and subsidiaries linked to the asset manager’s

entities based in Toronto, Bermuda and London, some of which were sold off in

2021. Some of the soy produced in the properties that contained deforestation

were sold to the controversial commodity trader Cargill, a company exposed

many times

for its links to forest clearance, and subsequently could have found its way

into British supermarket chicken.

At

least two British financial institutions, the Lancashire County Council Pension

Fund and the London Pension Funds Authority, have invested directly in

Brookfield’s Brazilian agricultural fund.

Soy warehouse in Mato Grosso state, Brazil. Brazil is the second largest soy producer worldwide. Paulo Fridman/Corbis via Getty Images

Brookfield’s “slash and sell”

tactics should not absolve it from responsibility for the environmental abuses

committed on its farms. Its ability to

cash in on deforestation underlines the need for governments to legislate to

stop the financing of forest destruction, rather than relying on voluntary net

zero initiatives such as GFANZ.

In response to these

allegations the company said it “unequivocally refute[s] the specific allegations made by Global Witness

– Brookfield has always acted in accordance with all applicable laws and

regulations. Brookfield is committed to the highest standards of ethical

behaviour across all our global investments, and we move quickly to address

issues when they arise.

"We have been invested in Brazil for over one hundred

years and we have been proud to support the country build and operate vital

infrastructure. While we are no longer

active in farming, timber or mining in Brazil, we continue to operate assets in

a range of sectors and we look forward to continuing supporting the country on

its development towards a Net Zero and thriving economy.”

Brookfield Asset Management

(BAM) indirectly controlled each farm named in this report, through Brazilian

investment funds and subsidiary companies. Where the name “Brookfield” is used

in the report this refers either to the Toronto headquartered BAM, to the Rio

de Janeiro-headquartered company Brookfield Brasil Ltda, which BAM held a

majority stake in via Brookfield Participacoes and Brkb Participacoes II, or to

Brookfield Agricultural Group, the brand name used by Brookfield Brasil in some

cases. The relationships between firms

in the Brookfield corporate umbrella named in this report is detailed in Annexe

C (please see the PDF version of the report for details).

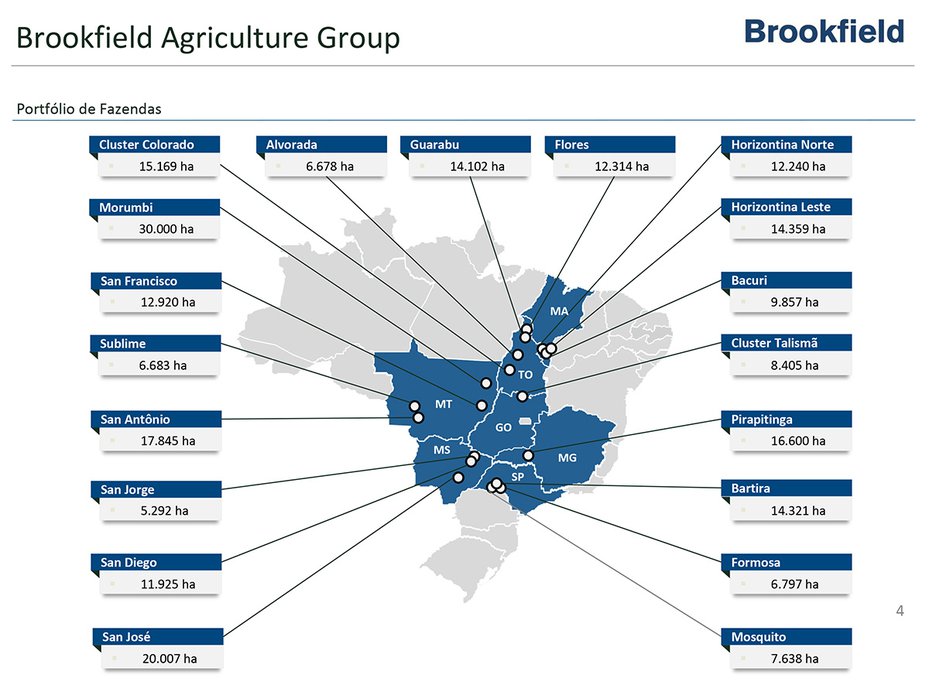

Early one October morning,

trustees of a San Diego pension fund gathered at their headquarters on the

outskirts of town to hear a pitch for an investment with an unusually high rate

of return: 20 to 25%. It was 2010, and the directors of Brookfield Agriculture

Group and Brookfield Brazil were cycling through a PowerPoint presentation

outlining how Brazilian cash crops could help grow the pension savings of San

Diego county’s teachers and civil servants.

It took them just over an hour to

convince the San Diego County Employees Retirement Association to invest $75

million in the Brookfield Brazil Agriland fund, more than a fifth of the fund’s

final value.

A flock of rheas is seen in a soybean field in the Cerrado plains near Campo Verde, Mato Grosso state, western Brazil. YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP via Getty Images

While Brazil’s recession of 2008

had led to banks foreclosing on farming estates and driven land prices down,

global demand for soybeans was rising fast, Brookfield directors said in their

presentation to the San Diego Pension Fund.

A boom in commodities like soy,

corn, sugar, livestock and timber meant alternative asset managers could earn

money both by selling these goods and by speculating on land prices. Crops

planted in the biodiverse Cerrado tropical savannah region would be

particularly lucrative investments.

Brookfield would acquire nearly

100,000 hectares (ha) of farmland through this fund over the next three years,

including at least five of the eight farms where we have identified

forest subsequently being destroyed to make way for crops, the legality of which

state authorities and Brookfield could not verify.

Brookfield told the San Diego

trustees who invested in its first Agriland fund that it was “a leader in

environmental stewardship.” Others eventually invested in this fund too,

including the Lancashire County Council Pension Fund and the London Pension

Funds Authority in the UK, according to data shared by the Anti-Corruption Data

Collective, potentially exposing council staff in the UK to deforestation

linked to Brookfield’s properties.

Agriland’s larger successor,

Agriland II, which San Diego pensioners also invested in, allowed Brookfield to

further expand its agricultural holdings after 2016.

Aerial view showing a native Cerrado (savanna) surrounding an agriculture field in western Bahia state. NELSON ALMEIDA/AFP via Getty Images

Brookfield first entered Brazil

in 1899 as the owner of a small private utility company and built São Paulo’s

first electric trams and first streetlights. It now holds immense energy,

infrastructure and agricultural holdings in Brazil – from natural gas pipelines

to hydroelectric and nuclear power plants, shopping malls, railways and a vast

network of farms.

By the end of 2020 it had nearly

doubled its agricultural land holdings to 267,000 hectares dedicated to

soybean, sugar, rubber, corn and cattle across 22 farms in seven states

compared to just 150,000 hectares of agricultural land a decade earlier, selling

14,500 heads of cattle a year. Its timber plantations spanned a further

275,000 hectares, and it sold more than three million cubic meters of logs and 16,200

tons of charcoal, according to its latest annual report.

Brookfield’s Brazilian assets were worth $22

billion in 2021 - including R$8 billion ($1.6 billion) in forestry and

agricultural assets - out of $391 billion in global consolidated assets.

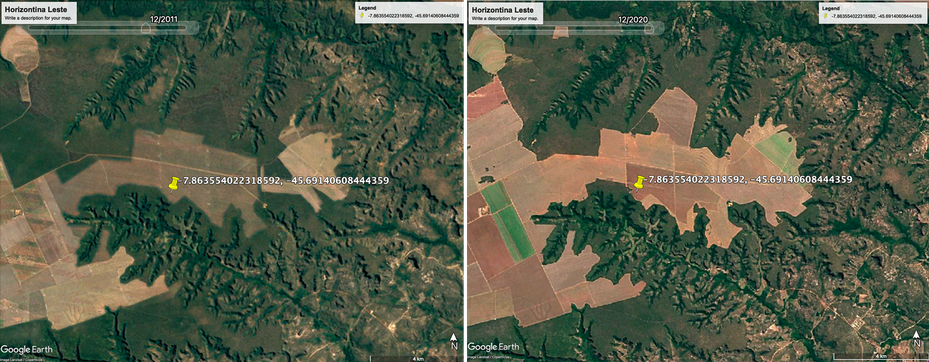

Satellite evidence

Left: East side of Horizontina Leste farm, December 2011, shortly before purchase by Brookfield. Right: East side of Horizontina Leste farm, December 2020, shortly before being sold by Brookfield. Both images from Google Earth

From the air, green tufts of

soybean form dark geometrical shapes in otherwise bald patches of tropical

savannah. The boundaries between forest and cleared land on Brookfield farms

are so straight they could only be human-made. Zoom in closer, and satellite images of giant steel silos appear to confirm

this. Once harvested, the crop could be used as protein-rich feed for Chinese or

British chicken, pork or beef, or will be turned into vegetable oil.

Nearly a decade’s worth of satellite

images and corporate filings show Brookfield’s soybean empire is responsible

for vast swathes of deforestation across three states in central-eastern Brazil.

We found evidence of forest

clearance on eight Brookfield “fazendas” in Tocantins, Maranhao and Mato Grosso

do Sul, namely the farms Horizontina Norte, Horizontina Leste, Nebraska, San

Diego, Nazare, Alvorada, Colorado and Onça Branca.

In total, around 9,000ha of

deforestation took place on these properties between 2012 and 2021, according

to our analysis of data from Brazil’s National Institute for Space

Research (INPE) and its land management system (SIGEF - see Annex A in the PDF

version of the report for details). The size of this clear-felled land is the

equivalent of 11,000 football pitches.

After the deforestation, the

farms were sold off to firms, including another investment fund in 2021, in an

apparent “slash and sell” strategy (see Annexe C in the PDF version of the

report for details).

Giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), in portuguese known as tamandua-bandeira, Bananal Island, Brazil. Jose Caldas/Brazil Photos/LightRocket via Getty Images

The eight farms are all in the

Brazilian Cerrado, a climate-critical biodiversity hotspot bordering the Amazon,

the rapid destruction of which could already be accelerating the pace of global

warming. Studies have shown it may store between 13.7 to 29.7 billion tonnes of

carbon dioxide. The lower estimate is similar

to the level of annual emissions by China, the world’s biggest emitter.

Roughly the size of Western Europe, this living and

breathing carbon sink is known as the “upside down” forest because its roots

reach up to 15 meters below ground level. Its ecosystem promotes stable

rainfall over the neighbouring Amazon rainforest and it feeds most of Brazil’s

river basins. It is home to endangered species including the jaguar, armadillo

and giant anteater.

The San Diego Pension Fund was offered comment on these

issues twice but did not respond. In contrast the London Pension Fund Authority

replied saying it took its “commitment to responsible investment seriously” and

that the fund was coming to its final stage of liquidation, but that it was

“not appropriate for us to comment on a fund manager’s behalf.”

The

Lancashire County Council Pension Fund also replied, stating that it “is

committed to protecting the long-term financial interests of all its clients”

and that it maintains “a responsible investment approach”, taking “accusations

of this kind very seriously”. It encouraged us to “speak to Brookfield directly”.

Brookfield denied the allegations, stating it “unequivocally refute[s] the specific

allegations made by Global Witness – Brookfield has always acted in accordance

with all applicable laws and regulations. Brookfield is committed to the

highest standards of ethical behaviour across all our global investments, and

we move quickly to address issues when they arise. We have been invested in

Brazil for over one hundred years and we have been proud to support the country

build and operate vital infrastructure.

"While we are no longer active in

farming, timber or mining in Brazil, we continue to operate assets in a range

of sectors and we look forward to continuing supporting the country on its

development towards a Net Zero and thriving economy.” When pressed on what

evidence they had that could substantiate its alleged refutation of the

allegations, it did not reply.

Brookfield’s involvement in

clearing the Cerrado’s climate-critical forests is not only environmentally

damaging, but occurred at a time when a variety

of studies

found the majority of the deforestation there to be of uncertain

legality.

Clearing of Cerrado vegetation of the subtropical savanna biome by burning in Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Jose Caldas/Brazil Photos/LightRocket via Getty Images

Lack of information and transparency on permitted deforestation

Despite filing freedom of

information requests to relevant state authorities, we were unable

to obtain permits that are needed to authorise deforestation under Brazilian

law for at least seven of the eight Brookfield farms identified. Our analysis

found around 6,700ha of deforestation at these farms between June 2012 and June

2021 – equivalent to 8,205 football pitches or more than half the size of San

Francisco. But Brazilian authorities were unable to provide information – meant

to be publicly available - on whether this was legal.

Fazenda Nebraska was the only

farm for which state authorities could share permits covering the time

deforestation took place.

Environmental bodies are meant to

publish information about deforestation permits in an official gazette easily

available to the public, under Brazil’s environmental transparency law of 2003.

But the legality of clearing at the seven farms could not be verified because state

authorities either failed to provide information or declined to answer our freedom of information requests for the deforestation permits. Some

even cited privacy concerns and said the farms’ owners would have to provide

the information. When we pressed Brookfield for evidence it had

that might show the legality of the forest clearance, it did not provide that

information.

Combines harvest soybeans near Tangara da Serra in the Cerrado part of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Paulo Fridman/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Neither Brookfield nor its

Brazilian arm appear to have a corporate policy committed to eliminating

deforestation from its farms or supply chain, making it unusual among major soy

producers. Brookfield Brazil’s latest annual report explains it is a member of

several external environmental or standards schemes.

This is despite well-established

links between soy and deforestation in Brazil, which produces around a third of

the world’s soy. The Cerrado, where the eight Brookfield farms we identified are located, is a particular deforestation hotspot for soy and

reportedly the site of 90% of deforestation linked to soy cultivation in

Brazil. The majority of national

production has shifted to this savannah land since soy producers vowed in 2006

to stop cultivating soy in the Amazon.

The omissions in Brookfield’s environmental

policies are particularly glaring because of its scale in Brazil, controlling

an $8 billion timber and agribusiness empire.

Fazenda Colorado, a soybean farm

in Tocantins state, was the site of 126ha of deforestation between September

2012 and July 2018, primarily in 2012 and 2014, according to our

analysis. Police found 42 farm workers living in slave-like conditions inside

the farm in 2014, 28 of whom were housed in a 70m2 square house with

no toilets or showers, according to court papers from November 2021 and local

newspaper reports.

The Brookfield-controlled firm

Brookfield Brasil Participacoes (BBP) was fined $800,000 for slave labour

offences at Fazenda Colorado, in a ruling upheld by a regional labour court in

December 2021.

The region between the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia, known as MATOPIBA in Brazil, is considered the showcase of Brazilian agribusiness. Fernanda Ligabue / Greenpeace

A Labour court in Tocantins ruled

in 2014 that both Brookfield Brasil Participacoes (BBP) and Indaia Agronegocio

(Indaia), Fazenda Colorado’s direct owner, were jointly liable for allegations

of workers being held in “slave-like” conditions at the farm in 2014. The firms

were condemned to pay a R$800,000 ($163,000) fine - a ruling they both

appealed.

Despite their argument to the

contrary, Indaia was controlled by BBP according to the court. Renato Cassim

Cavalini, who at the time was CEO of both Brookfield Agricultural Group and

Vice-President of Brookfield Asset Management, was director and controlling

shareholder of both Indaia and BBP, the court said. Brookfield Brasil

Participações 010 and Brookfield Brasil Participações 011 are both listed as “companies

under common control” of Brookfield Brasil Asset Management Investimentos

(BBAMI), in a document filed to the CVM, Brazil’s securities and exchange

commission in 2015 and updated in April 2021. BBAMI is an investment fund directly

controlled by Brookfield Brasil Ltda and indirectly controlled by Brookfield

Asset Management in Canada and BHAL Global Corporate Ltd in the UK, amongst

others, according to this document.

BBP had previously argued it did

not share direction, control, administration or partners with Indaia. But in December

2021, a regional court upheld a judgement that recognised both companies as an

economic group, ordered them to pay the amounts jointly and rejected the

appeal. Indaia denied being responsible

for the working conditions, said it complied with labour standards, and argued

it was not responsible for the work done, which had been merely to clean the

soil, and that labourers had been free to choose where to sleep. BBP denied

corporate ownership or responsibility for Indaia, according to court documents

from November 2021. Both

Indaia and BBP appealed the decision in the Superior Labour Court (TST) and in

June 2022 were awaiting a decision.

Brookfield expanded its British

modern-day slavery and human trafficking policy in 2021 to cover its operations

globally. The modern slavery statement referenced in its latest ESG report

says: “Our strategies to prevent modern slavery are designed to be

proportionate to the risks identified and are addressed and mitigated taking

into account the nature of the risks and of the assets and operations to which

they apply, the geographic location and sector, the economic, political and

regulatory environment, and our assessment of the benefits to be derived from

such mitigation measures.” These commitments appear to stand in contrast to its

actions in the ongoing slave labour case.

In response to these allegations Brookfield said

“in 2014, we became aware of a contractor

contravening labour laws when working on one of our sites. We took immediate

and decisive action. Despite a court ruling recognizing that these were not our

employees, we chose to honour the contractor’s compensation obligations (while

maintaining our right to claim against it) and worked to put considerably

stronger safeguards in place thereafter.” When asked if denying corporate

ownership of the property constituted “decisive action”, Brookfield did not

reply.

A former slave labourer demonstrates how he cleared brush with his sickle, in Piauí state, Brazil. Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images

Brookfield appears to be in

breach of the membership guidelines of the Round Table on Responsible Soy

(RTRS), a Swiss voluntary certification scheme. Brookfield Brasil highlights its

farms’ membership of the RTRS in its annual report for 2020-2021.

The RTRS prohibits the clearing

of any “natural land” for soy in Brazil after 2016, including any land with

natural vegetation such as Cerrado land. It endorsed the “Cerrado Manifesto” in 2017, a

zero-deforestation pledge.

But 1,900 hectares of

deforestation took place at eight Brookfield farms on Cerrado land between the

start of 2016 and June 2021, our analysis of official data suggests.

All of these farms were registered with soy production as their primary aim, according

to unofficial corporate data available online.

Satellite images of soy storage bins at Fazenda Nebraska in June 2019, after it had been acquired by Brookfield Agricultural Group, left (Credit: Planet Labs Inc.) and July 2021, just before it was sold (Credit: Maxar Technologies).

Satellite images of apparent soy storage bins at Fazenda Horizontina Leste in December 2015, after it had been acquired by Brookfield Agricultural Group, left (Credit: Planet Labs Inc.) and in April 2022 after it was sold (Credit: Maxar Technologies).

Despite this, the asset manager highlights

its certification by the RTRS and explains the voluntary organisation seeks to guarantee

that soy comes from an “environmentally sound” process.

Companies controlled by Brookfield

combined to make this group the sixth largest soy producer to be actively

registered with the RTRS in Brazil, producing 118,967 tons of soy registered

with the scheme in 2020. Overall it produced 208,000 tons of soy, according to

its latest annual report.

At the time Brookfield had

executive ties to the certification organisation. In 2019, the director of

Brookfield Agricultural Group, Luiz Iaquinta, was made treasurer and a member

of the RTRS’s executive board. While working for Brookfield he also served as

chairman of the RTRS’ taskforce in charge of its communications and spoke at

one of its panel discussions in 2020.

When

informed of these allegations the RTRS said it was “pleased to see an extensive

report dedicated to this important topic”. It went on to say that “Brookfield is not a member of RTRS. A company mentioned in your report “Bartira

Agropecuária S/A” is, however, both RTRS member since 2015 and the holder of a

multisite certificate. Out of the farms mentioned in your report, only

Horizontina Norte and Horizontina Leste are included within the scope of the

certificate under the multisite type.”

RTRS added that “it sets the principles

and indicators that must be complied with for a certificate to be issued” and

that the audit “process is conducted by independent certification bodies which

must have been previously approved by independent accreditation bodies. In the

case of the certificate issued to certain farms operated by Bartira

Agropecuária S/A, the certification body in charge of the process is Control

Union Certificates.”

It further

noted that in “all cases, RTRS President, Vice-presidents and also the

Treasurer follow the instructions expressly given by the Executive Board. The

fact that Bartira Agropecuaria S/A has been elected by the members of the

association as Executive Board member and, subsequently, the members of the

Executive Board elected Mr. Iaquinta as Treasurer does not provide such member

or individual with any special power or influence over the association.” For

its full response please click here.

British supermarkets may be linked to the deforestation of the Brazilian Cerrado

British supermarket chicken

Some of the chicken sold at

British supermarkets in recent years may have been fed on soy originating from

one of Brookfield’s deforested farms.

The commodity trader Cargill

admitted in 2019 to buying soy from Brookfield’s Fazenda Nebraska, after a

report from the NGO Mighty Earth identified deforestation and a forest fire at

the farm. This farm was the site of

1,951ha of deforestation between 2014 and 2021, according to our

analysis.

Cargill is the United States’

largest private company by revenue, according to Forbes, and has reportedly led

corporate resistance to a moratorium on soy production in the Cerrado. Cargill

ships more than 100,000 tonnes of soya beans to the UK every year from Brazil’s

threatened Cerrado savannah, according to an estimate by the Bureau of

Investigative Journalism. Its analysis linked these beans to chickens

sold at Nandos, Asda, Lidl and Tesco, via Cargill’s soy crushing plant in

Liverpool and its poultry feed mills in Hereford and Banbury.

About a fifth of the soy imported

to the European Union (EU) from the Amazon and Cerrado regions comes from

illegally cleared land, according to a 2020 study in the academic magazine

Science.

View of soybean terminal of Cargill corporation in a river port of Santarem. Matyas Rehak via Shutterstock

When informed of these

allegations Nando’s stated it was “acutely aware of the devastating impact

deforestation is having, not only on climate change, but also on ecological

collapse. We work hard to ensure that our supply chain is not linked to

deforestation and that all our soy is sourced under the Round Table on

Responsible Soy (RTRS) or equivalent certification and now encourage mass

balance soy purchases as a minimum standard. These commitments apply not only

to the soy we use as a direct ingredient but also to our supply chain.”

It

added that this year it had “also joined the UK Soy Manifesto, alongside our

suppliers, further cementing our position to ensure all our soy is

deforestation and conversion free and setting expectations of this in our

latest food policy for suppliers. Alongside this, we continue to work closely

with experts and suppliers to research more sustainable alternatives to soy for

use in animal feed.”

Lidl said it operated “with a

fundamental respect for the human rights of the people we interact with and

take this responsibility extremely seriously. As such, we are committed to

implementing due diligence on this topic, improving working conditions and

upholding human rights at all levels of the supply chain, in line with the UN

Guiding Principles.”

Cargill stated it had “prioritized the adoption of policies across our supply chains, including

our Policy on Sustainable Soy – South American

Origins, and our Commitment on Human Rights. We strive to abide by these rules

and expect the same level of commitment from our suppliers as detailed in our Supplier Code of Conduct.”

It went on to say it had “robust

procedures in place to ensure we are respecting social and environmental

restrictions - Slave Labor, Soy Moratorium, Green Grain

Protocol and Embargoes (from federal and state agencies) - which includes respecting regulated

indigenous areas, from which we do not source grains. We monitor our suppliers against these criteria

and embargo lists and can confirm the farm in question is in compliance. As always, if we find any violation of our

policies and commitments, the producer will be immediately blocked from our

supply chain.”

Asda and Tesco did not reply to offers for comment.

Soya Production in the Cerrado Region, Brazil. Harvest in the municipality of Riachão das Neves, in the state of Bahia. Greenpeace

Carbon footprint: over a million red-eye flights

Brookfield claims to be a

responsible and sustainable investor, and at the time of writing, the front

page of its website showcased Mr Carney’s newspaper pieces and videos on green

finance.

Our analysis

estimates the deforestation found in Brookfield’s farms over nine years

released 600,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide, equivalent to flying from London to

New York 1.2 million times (1,217,038 flights at 493kg of CO2e per flight). This

analysis is based on an estimate of the tropical biomass present on the eight

farms before deforestation took place (see Annexe A in the PDF version of the

report for the methodology).

This poor track record raises

questions about how Brookfield will meet its new commitment to net zero by 2050

as part of its GFANZ membership. Tropical forests store vast quantities of

carbon and their destruction accounts for the majority of carbon dioxide emissions

that come from land use and land use change, according to the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change.

Brookfield Brazil says its own

greenhouse gas inventory for agricultural operations showed its farms captured

309,000 tons of carbon “through biological sequestration” in the 2019/20

harvesting period. It did not explain how this sequestration took place, or

whether this considered deforestation but said two of its farms were accredited

with Cargill’s net zero program.

Dr Ed Mitchard, a University of

Edinburgh professor who specialises in mapping natural carbon stocks, advised

on our carbon accounting. He warned against companies continuing to

deforest tropical regions and reaching net zero by using offsets.

He said: “Fundamentally in Brazil

we need to stop cutting down trees. Deforestation is already making

temperatures higher, causing more drought, more fires, impacting more trees and

we will get more of this vicious circle in the coming decade.”

“There was great fanfare at

GFANZ’s launch but if it’s not trickling down to what high profile members are

doing in terms of land ownership that is very worrying, and suggests these

large corporations are intending to carry on with business as usual.”

Brookfield is no stranger to

controversies over carbon accounting. In February 2021, six months after he was

hired by Brookfield, Carney claimed at a Bloomberg conference that his employer

had a net zero emissions impact across its entire portfolio due to its

“enormous renewables business that we've built up and all of the avoided

emissions that come with that”. He later retracted this claim, which had been

based on a controversial method of offsetting emissions by measuring those emissions

that were “avoided” through the consumption of green energy assets Brookfield

has invested in.

Brookfield Asset Management’s Asia-Pacific headquarters. Lisa Maree Williams/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Foreign companies are banned from

owning more than a quarter of the land in any Brazilian municipality, under a

2010 legal interpretation of existing restrictions on foreign ownership of

Brazilian land. This includes

firms registered in Brazil but ultimately controlled from abroad, like

Brookfield.

“Brookfield’s elaborate financial

strategies are interesting because these have traditionally been used to

circumvent Brazilian laws on foreign land ownership,” said Junior Aleixo, a

sociologist at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro, who wrote his

thesis on Brookfield’s land ownership model in 2019 as part of GEMAP, a public

policy and agribusiness research group.

Aleixo added: “These strategies facilitate

control of the land while making its ownership deliberately difficult to pin

down.” “The ecological impact is very high, as most of these funds are more

concerned with the fluctuation of land and commodity prices than with the

economic redistribution and socio-environmental impact of their investments.”

Because Brookfield does not

publish an up-to-date list of its direct and indirect farm holdings in Brazil,

it is not possible to establish how close its farm holdings come to this limit

and whether they exceed it.

One of Brookfield’s strategies

has been to invest in farmland through investment funds. Brookfield Brasil

Asset Management Investimentos (BBAMI) and Brookfield Brazil Agriland fund

indirectly controlled the farms Horizontina Leste, Nebraska and Horizontina

Norte until 2021, according to sale documents provided to the Brazilian securities

and exchange commission, the CVM. It also indirectly controlled Caiapo Agronegocio

and Macaubapar Participacoes, linked to the Nazare Group of farms, Alvorada and

Talisma.

A Brookfield-controlled firm called Agripar

Participações, of which the Agriland fund was a shareholder as of 2012,

indirectly controlled a number of farms, Horizontina Norte, Horizontina Leste,

Alvorada, Talismã and Colorado, according to a 2017 presentation by the asset

manager.

Extract from a Brookfield presentation on Fazendas Bartira

Another indirect acquisition strategy

has been the issuance of Certificates of Agribusiness Receivables (CRAs),

tradable credit instruments which pay investors a monthly fee and are backed by

agricultural land. Brookfield’s Brazilian farm holding group Bartira

Agropecuária raised R$70 million in 2016 through issuing CRAs, according to

Aleixo’s research.

Brookfield reportedly bought

these securities from Bartira – which it already owned - via a financial

services firm, then transferred the funds back to Bartira, which in turn used

the money to buy more land through Brazilian-registered farming companies. The

2017 presentation shows that Bartira controlled the deforestation-linked San

Diego farm, where we found 545 hectares of cleared forests.

Brookfield has also used

debt-to-equity swaps to control its farming empire, where it buys debts in a Brazilian

company which are then transformed into stocks. In 2017, the Agriland fund,

reportedly bought debentures, a type of loan agreement, in Embaúba

Participações, the Brazilian indirect owner of Fazenda Nebraska, on the

condition these would be converted into shares as soon as Embauba was able to

acquire rural properties. We found 1,952 hectares of deforestation

at Fazenda Nebraska between 2014 and 2021.

Sell-off

Brookfield’s CEO Bruce Platt has

said in interviews that

the company buys distressed assets during crises and sells them once the price

has gone back up. “We’re in the business of owning the backbone of the

global economy,” he told the Financial Times in 2018. “[But] what we do is

behind the scenes. Nobody knows we’re there, and we provide critical

infrastructure…”

He went on to describe the

company’s strategy in Brazil: “ … there was an enormous void of foreign direct

investment into Brazil, therefore we bought a lot of things at what we deemed

to be fractions of the replacement cost.”

Filings to the CVM show that

Brookfield sold off many of the indirect owners of its Cerrado farms in August 2021,

including those of Horizontina Leste, Horizontina Norte, Nebraska,Nazaré,

Alvorada and Talisma. It reportedly sold 100,000ha of farmland to

the real estate fund Terrax FII in August 2021, after selling another 130,000ha

earlier in the year.

The Cerrado is a tropical savannah covering 23% of the surface of Brazil, or two million square kilometres, half the size of the European Union. It has lost about 50% of its natural vegetation. Marizilda Cruppe / Greenpeace

The financialization of Brazil’s

climate-critical land could be set to continue. In 2021 the Brazilian senate

approved a new tax-efficient category of investment fund, known as FIAGRO,

which makes it easier for foreign financial institutions to invest in Brazilian

agriculture. It has specific provisions to encourage lenders, insurers, venture

capitalist and financial technology companies to invest in rural land without

breaking foreign ownership rules, by acquiring shares in funds which hold

titles to these lands.

As Brazil seeks to attract more

investments into its land use sector, Brookfield’s failings show how regulation

in the UK, the US and the EU is required, to ensure the financial sector

carries out continuous due diligence on deforestation before and after entering

into such ventures.

Deutsche Bank, Bank of America and HSBC: complicit in Brookfield’s forest destruction?

Brookfield Asset Management could

not fund its operations, including forest destruction, without the backing of

some of the world’s biggest financial institutions, including Deutsche Bank,

Bank of America and HSBC, according to our analysis, published in

2021. Our dataset drew on publicly available financial data compiled by the

Dutch non-profit Profundo, to identify which financial institutions were

providing crucial shareholdings, bond holdings, loans, revolving credit

facilities and underwriting services to 20 of the world’s most notorious

agribusinesses linked with forest destruction between 2016 and 2020.

Deutsche Bank declined to

comment when contacted by us in 2021 about its investment in 19

agribusinesses accused of deforestation, including Brookfield. It has signed

the UN Principles for Responsible Banking, which commits banks to the Paris

Climate Agreement Goals, and has also said it will not finance the destruction

of primary forest, High Conservation Value or peatlands, illegal logging, and

uncontrolled or illegal use of fire where there is clear and known evidence of

any of these harms taking place. But it stopped short of prohibiting the

financing of all deforestation and implied some forest loss would be acceptable

if offset through tree-planting.

Deutsche Bank AG’s headquarters in Frankfurt, Germany. Martin Leissl/Bloomberg via Getty Images

In response to the allegations

about Brookfield, Deutsche Bank said “as a matter of policy we do not comment on

client relationships - not even potential or former ones” but that it had a “clear set of guiding principles and requirements

that we apply to our client and business selection processes in order to

promote sustainable agribusiness. As part of this approach, we require clients

to participate in certification schemes and expect them to publicly demonstrate

their commitment to No Deforestation standards.

"We do not knowingly finance

activities that result in the clearing of primary forests, involve illegal

logging or conversion of High Conservation Value, High Carbon Stocks forests or

peat lands. Where we work with conglomerates, we make a significant effort to

ensure our financing is only directed to activities that are in line with our

policies.”

Bank of America, with whom

Brookfield had the second most significant banking relationship by size of

combined lending, investing and underwriting, says it supports reforestation

projects in dozens of US cities. Its most recent forest policy says it will not

underwrite bonds where proceeds are specifically used to clear primary forest

or for the unauthorised clearance of high conservation value forests.

It also

says it will not finance operations in areas where indigenous land claims are

not settled. Our data suggests Bank of America funnelled an

estimated £1 billion into Brookfield between 2016 and 2020, primarily by

under-writing bond issuances. When offered comment on these allegations it did

not reply.

Asset managers Citigroup, Vanguard

and Blackrock, all US-based, were some of Brookfield’s biggest

investors. Two years ago, Blackrock’s chief executive Larry Fink wrote to

clients that he considered climate risk an investment risk, and that the firm

would make sustainability its new standard for investing.

When contacted in

2021 about its exposure to firms accused of deforestation, including

Brookfield, Blackrock told us it does not provide direct financing

or lending facilities to individual companies and does not control the

strategic decision-making of businesses in which it is a minority shareholder. It said 90% of its equity holdings are through

index funds or Exchange Traded Funds in which clients choose where to allocate

their assets. When offered comment on the allegations against Brookfield in

this report, none of these investors responded.

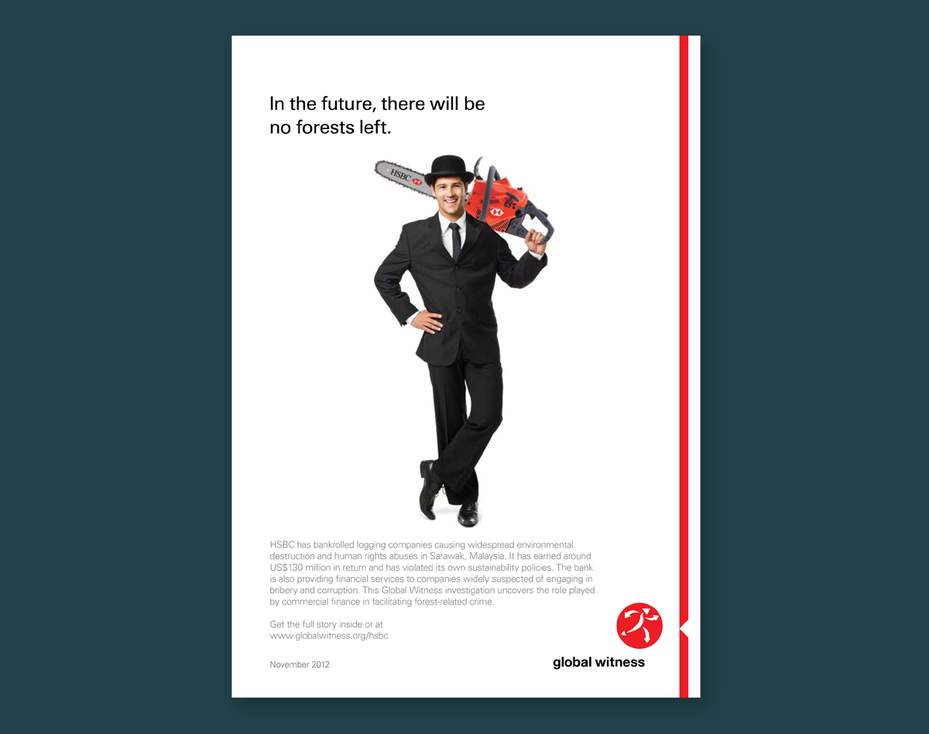

The third largest banking relationship was with HSBC,

the British bank, which channelled £880 million to Brookfield, also primarily

in the form of underwriting its bond issuances. HSBC made a public commitment

to stop financing firms accused of deforestation in 2017. In 2021, the bank

told us its relationship with 19 destructive agribusinesses

including Brookfield were either not linked to forestry, palm oil or cattle, or

that the relationship had ended or was in the process of ending.

The bank said

in some cases, it had only indirect relationships with the agribusinesses as

nominal manager of its shares on behalf of a customer, meaning it had no

beneficial interest in or direct influence over the underlying agribusiness.

HSBC has been linked with several controversial agribusinesses and has been involved in deals with top deforesters worth an estimated $6.85 billion since 2016. Global Witness

On the Brookfield allegations and

its financial link to the company, HSBC stated it could not “confirm whether or

not a customer relationship exists” and was therefore not “able to comment on

this company directly”. It added that it “recognise[s] the importance of

protecting forests and Indigenous peoples and this is incorporated in HSBC’s

approach to deforestation and related issues which is set out in our

Sustainability Risk policies on Forestry

and Agricultural

Commodities, which incorporate No Deforestation, No Peat and No

Exploitation requirements, and the use and support of credible independent

certification schemes. For investments, our Asset Management business has Engagement

policies including one dedicated to Biodiversity

related issues.”

These banks and asset managers

have all featured in previous Global Witness reports on deforestation.

Other British financial

institutions had significant exposure to Brookfield too. The Lancashire County

Council Pension Fund and the London Pension Funds Authority have both invested

directly in Brookfield’s Brazilian agricultural fund.

Deutsche Bank, Bank of America

and HSBC joined the Net-Zero Banking Alliance that sits under GFANZ in April

2021, after the financial analysis discussed in this section was published by Global

Witness last year. This analysis

demonstrates the scale of investment by GFANZ members in carbon intensive,

deforestation linked businesses, including Brookfield.

Mark Carney, UN Special Envoy on Climate action and Finance, and Co-Chair of GFANZ, speaks during the Net Zero Delivery Summit at the Mansion House. PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Mark Carney: A poster boy for green finance

Mr Carney’s best-selling book Values

and speeches as UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance preach a simple

idea: climate change can be stopped if large banks, pension funds and asset

managers voluntarily change their investment habits to reduce carbon emissions.

“Finance is no longer a mirror

that reflects a world that’s not doing nearly enough. It’s become a window

through which ambitious climate action can deliver the sustainable future that

people all over the world are demanding,” Carney said in a keynote speech at

COP26 in November 2021. “It will help end the tragedy on the horizon.”

Mr Carney’s financial experience,

network of political contacts and UN Special Envoy status give credibility to

the idea that financiers can be trusted to act on climate change. After more than a decade as head of the

Bank of Canada and then the Bank of England, Mr Carney was appointed financial

adviser to the UK government for COP26. He also launched an international

taskforce on carbon credit markets, to help companies use controversial “carbon

offsets” to reach net-zero emission goals.

Mark Carney leaves 10 Downing Street. Leon Neal/Getty Images

“The personal clout of men like

Carney is remarkable because they provide a way to lend the credibility of ‘we

understand business and finance’ to the climate space and make it a business

issue rather than a hippy green issue,” said Adrienne Buller, a green finance

researcher and senior fellow at the thinktank Commonwealth. “But their framing

of climate commitments around net zero is a get out of jail free card because

it only zeroes in on a portion of their assets.”

Mr Carney’s decision to accept a position at Brookfield

while acting as UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance, as well as special

adviser to the UK government on COP26, raises important questions about his

role in promoting weak voluntary schemes that do not effectively prevent the financing

of deforestation or other environmentally damaging businesses and activities.

Mr Carney was appointed

Vice-Chair and head of sustainable investing at Brookfield in August 2020, a

year before any of the nine farms highlighted in this report were sold off. His

base salary at Brookfield is thought to be well above the £879,000 he earned as

governor of the Bank of England and the asset manager openly says it gives

senior leadership team “significant” stakes in the firm. He became Chair of the firm in December 2022.

When offered comment on these

responses, Brookfield replied stating the “allegations refer to periods of time

long before Mr. Carney joined Brookfield and to businesses in which Mr. Carney

had no involvement. Moreover, Mr. Carney has demonstrated considerable

leadership in Brookfield’s transition investing strategy since its launch in 2021,

including spearheading the fundraising and deployment of the world’s largest

climate impact fund.”

Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ): flawed by design?

GFANZ is central to Mr Carney’s climate and finance vision. Launched

in April 2021, GFANZ aims to ‘broaden, deepen and raise

ambition’ to meet the Paris Agreement by creating a united financial sector-wide

net zero alliance. It currently represents 450+ member firms, with more than $130 trillion in assets under

management and advice.

The Eiffel Tower was illuminated in green to celebrate the ratification of the COP21 climate change agreement in Paris. Geoffroy Van Der Hasselt/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Individual financial institutions belong to GFANZ through industry-specific

subgroups. For example, Brookfield is a member of the Net Zero Asset Managers

initiative, and its backers Deutsche Bank, Bank of America and HSBC are members

of the Net-Zero Banking Alliance.

GFANZ signatories originally signed up to

mandatory criteria set by the Race to Zero, the UN standard setter for

non-state net zero commitments, including a commitment to half their emissions

by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050. Deforestation

became a key aspect of the Race to Zero criteria in June 2022, with new and

existing members – including Brookfield – required to pledge to achieve and

maintain operations and supply chains free of deforestation by 2025 at the

latest.

In September 2022, GFANZ

co-chairs, including Mark Carney, issued a press release warning that broader net

zero targets are unattainable without immediate action to end the financing of

deforestation, with the need to end all land conversion by 2030 at the absolute

latest to limit global temperature rises to 1.5°C.

The Science Based Target initiative (SBTi) –

which assesses and certifies private sector emissions targets – also

requires companies

have a

target date of eliminating deforestation by 2025 or earlier for a target to be

scientifically validated. In line with this, GFANZ's guidance on transition plans recommends financial institutions should have deforestation policies and embed their net zero targets into all investment decision-making tools and processes.

While this guidance recognises that ending deforestation financing is an urgent priority, GFANZ itself does not have the power to compel its members to meet their voluntary targets and the alliance appears to be reducing, not building, credible monitoring and accountability controls.

In October 2022, GFANZ announced it would no longer be mandatory for its member alliances to adhere to the UN Race to Zero targets and criteria, citing that all of its sector-specific alliances "are independent initiatives subject only to their individual governance structures", with "sole responsibility" for changes to their targets and membership criteria. Prior to this, the alliance described itself as "anchored" in Race to Zero to ensure "credibility and consistency".

GFANZ split from Race to Zero shortly before the planned introduction of an "independent compliance mechanism" by that body, with multiple media reports claiming some financial institutions threatened to quit the alliance over antitrust concerns related to more stringent fossil fuel phase-out criteria issued by the UN. GFANZ members must now only "take note" of the advice and guidance issued by Race to Zero, with sector-specific alliances free to set their own standards and targets in the absence of any independent monitoring and accountability functions. This episode demonstrates how easily voluntary initiatives governed by the financial sector can succumb to internal pressure to roll back climate targets and standards.

GFANZ itself has no capacity or resources dedicated to monitoring and verification, and although some sector-specific alliances have designed their own so-called "accountability mechanisms", these procedures lack transparency and independence. For example, the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative to which Brookfield belongs requires the submission of an annual report to a group known as the "Network Partners", which is made up of a further six alliances, demonstrating the labyrinthine complexity and lack of transparency in the governance model of the Race to Zero and GFANZ.

By contrast, the Net-Zero

Banking Alliance, which describes itself as a "bank-led initiative", is

ultimately governed by a Steering Group made up of 12 financial institutions, including

high level representatives of HSBC and Bank of America, who are historic backers of companies such as

Brookfield, as discussed above.

Forest fire in Mato Grosso state, Brazil, 2021. Greenpeace

That GFANZ

is co-chaired by Mark Carney – who is in turn Chair of Brookfield –

demonstrates the contradictions and conflicts of interest that arise when governments rely on the financial

sector to design and implement pledge-based voluntary schemes with no fully transparent

monitoring or accountability mechanisms.

Brookfield denied the allegations, stating it “unequivocally refute[s] allegations of a conflict of interest between Mr. Carney’s outside interests and his connection to these historical allegations”.

In response to these allegations GFANZ said in August 2022 it expected all of its “members, including Brookfield, to meet the requirements of their sector-specific alliances and Race to Zero.” It went on to add that although it could not “comment on specific allegations made about member firms, we can observe that thus far, Brookfield has adhered to all relevant NZAM and Race to Zero policies. Brookfield has adopted targets for one third of its assets under management, committing to reduce emissions by two-thirds from these assets by 2030. We will continue to support all financial institutions in establishing robust plans, targets, and metrics that align with net zero.”

It clarified that the “GFANZ Recommendations and Guidance on Financial Institution Transition Plans, which are currently out for consultation with the intention of being finalized by COP27 this November, recommends that financial institutions establish rigorous policies for ending the financing of carbon-intensive activities such as deforestation. Grounded in the requirements of Race to Zero, GFANZ expects financial institutions to set targets that align with 50% emissions reductions by 2030 and support an end to deforestation by 2025.”

It concluded that it appreciated the “scrutiny and high expectations civil society has for GFANZ.” Race to Zero did not reply to an offer for comment.

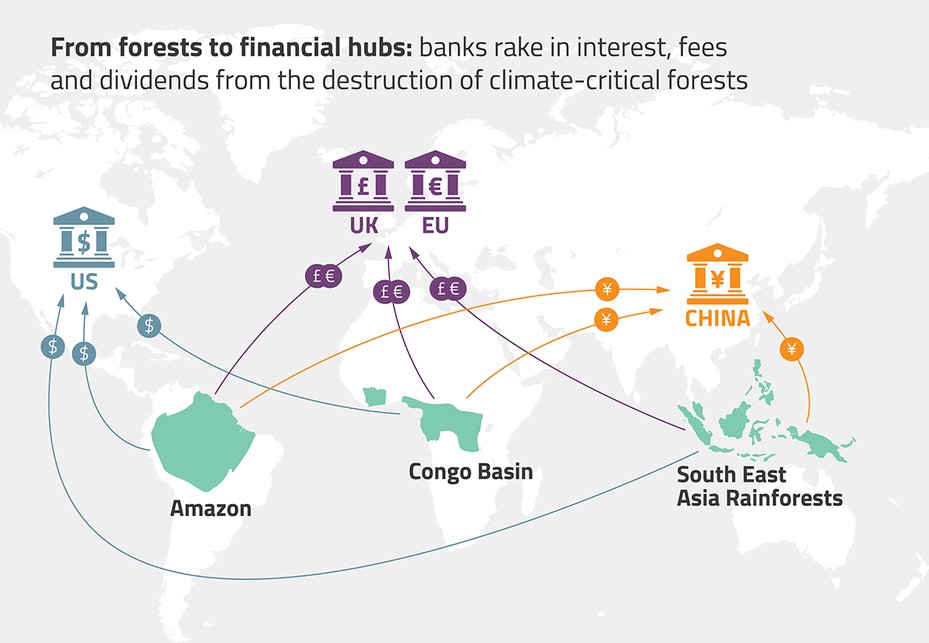

Financial institutions have netted $1.74 billion in interest, dividends and fees from financing the parts of agribusinesses groups that carry the highest deforestation risk. Global Witness

Governments are missing in action

Existing financial regulation and voluntary schemes

have failed to prevent the financing of the destruction of climate-critical

forests, mainly due to the same lack of monitoring and accountability

highlighted above. Instead, new laws are needed to meet 2025

deforestation targets, by preventing and remedying the financing of forest

clearance and human rights abuses. Clearer climate-related legislation is, in

fact, already supported by GFANZ. Responding to us, GFANZ stated it

would “like nothing more than for governments to make net zero transition

planning mandatory and transparent, but are stepping in absent government action.”

At COP26, over 140 governments representing 90% of the world’s forests pledged

to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030, including through

the ‘alignment of

financial flows with international goals to reverse forest loss and

degradation’. This necessitates a new preventative approach to financial regulation. Ahead of COP27, GFANZ called on G20 governments to "Translate commitments to safeguard nature and prevent deforestation into tangible government policies that can cascade through the private and financial sectors."

To date, however, governments in key financial

centres including the UK, EU and US have relied on inadequate voluntary certification

schemes and financial-sector initiatives, rather than introducing new regulations

to stop institutions from making such investments in the first place. Neither

the EU, UK nor the US have legislation requiring financial institutions to

conduct due diligence specific to deforestation risk.

Greenpeace campaigners cover the EU Commission’s headquarters with giant image of Amazon fires. Tim Dirven / Greenpeace

In the UK, under Section 17 of

the Environment Act, it will soon be illegal for large businesses to use commodities

such as soy if they were grown on illegally deforested land, yet financial

institutions will continue to profit from these deals with impunity. The EU recently agreed similar legislation

requiring traders to conduct due diligence to check if commodities were grown

on deforested land. That law commits to a forthcoming review of the role of

European financial institutions in driving deforestation.

In the US meanwhile, the

Fostering Overseas Rule of Law and Environmentally Sound Trade (FOREST) Act has

received bipartisan support for banning agricultural commodities produced on

illegally deforested land from entering the US market, but also fails to introduce

due diligence for the financial sector.

Without action to introduce or extend new regulations

to prevent financiers from bankrolling deforestation, these commodity-focussed

pieces of legislation are severely undermined from the outset, jeopardising the

Paris Agreement’s objective to limit global temperature rises to 1.5

°C.

Rubber tappers hungry for latex

to waterproof shoes and cloaks were the first to invade traditional Kayabí

territories on the banks of the Teles Pires river in the 19th

century. Gold miners and hydroelectric dam builders followed in the 20th

century, to make a quick buck off the south-eastern Amazon’s energy and soil

wealth in Mato Grosso and Pará states.

A Dam being built in the Teles Pires river. Greenpeace

The Amazon is home to some 300

indigenous groups including 80 groups of “uncontacted peoples”, who have had

limited contact with the outside world. Just a few hundred Kayabí people still live

along the Teles Pires river’s banks in Mato Grosso and Pará states, on a

protected corridor of land meant to preserve a slice of history and stem

agricultural expansion into the Amazon.

The latest threat to this

endangered Kayabí community’s land appears to be an asset manager headquartered

in Toronto nearly 4,000 miles away. Until January 2022, Brookfield Brazil was

the direct owner of Agropecuaria Vale do Ximari (Ximari), a farming company

that claimed it bought the rights to cattle farming, mining and timber logging

on the land in 1998, incorporation documents show. Under Brazil’s Constitution

and the 1973 Law for the Protection of Indigenous Peoples, lands on which

indigenous people have historically lived and which are in the process of being

certified cannot be sold.

The Kayabí have lived in fear of eviction since

Ximari obtained an injunction ordering police to clear all inhabitants from

75,000ha of land in 2018. The indigenous community living on this farm –

understood to be made up of at least six families and eight children – use the

charcoal-rich land to farm nut, corn and cassava varieties as well as hunting

its wild pigs, tapirs and the occasional jaguar.

All over Brazil, faraway foreign investors are pressuring indigenous groups to leave the land their ancestors have occupied for hundreds if not thousands of years.

Frederico Oliveira, an associate professor of anthropology at Canada’s Lakehead University who has previously spent four years researching the Kayabí.

While these investors may see the Amazon as a way to extract resources and generate wealth, land grabs strip indigenous groups of their constitutional rights to places they consider sacred, where their ancestors are buried and where they hope to bring up their children.

Kayabi hunting lodge near Lake Jabuti. Dr Oliveira

The decades-long conflict over

land between the Brookfield-owned farm and the Kayabí indigenous community has

unfolded on land containing rare biodiversity, in the world’s largest

rainforest. Scientists published in the Nature Climate Change journal in

2022 wrote that the destruction of the Amazon could have “profound implications

for biodiversity, carbon storage and climate change at a global scale”. Forest

loss in the Amazon in 2022 has risen to its worst rate for 15 years, according

to Brazil’s national space research institute INPE. Scientists have warned the biome could soon

reach a tipping point where it stops being able to sustain attacks and its

trees start dying en masse.

Implementing the eviction order

and removing the Kayabí could set a dangerous legal precedent, paving the way

for more mining projects backed by international asset managers on previously

protected Amazon land.

Living with the threat of eviction

A bloody river battle would take

place if the police executed the court injunction to clear two Kayabí villages,

according to a letter from an operational commander in the Mato Grosso military

police force, Abel Rodrigues Pereira, to his superior in June 2018, obtained by us. The villages are on just 40ha of land overlooking the Teles

Pires, located a car and boat journey of more than 100km from the nearest town

of Apiacas, along roads and treacherous rapids. The Kayabí community living

there has in the past told justice officials that it had no intention of

leaving. Indigenous villages dotted around the river could be inclined to show

solidarity, the letter said.

Two dozen police officers, six

four-by-four cars, five boats, a garrison of firefighters and aerial back-up in

the form of a helicopter would be required over seven days for the eviction

operation. Female medical staff would need to accompany the battle squad in

anticipation of injury of indigenous women who they said were particularly

likely to fight back.

Mato Grosso’s state military

police have refused to clear the land of people, citing lack of capacity and

reputational risk, and asked the federal police to do so instead. The eviction

order was still pending after the sale of the farm four years later in May

2022, despite repeated pleas from Ximari for it to be enforced.

Ancient land rights

The Kayabí’s presence along the

Teles Pires river has been carefully documented since the early 20th

century through interviews by anthropologists. Research commissioned by the

Brazilian government body for the protection of indigenous rights, FUNAI,

confirmed this.

Large scale deforestation of the

Amazon started with the construction of a Brasilia to Belem highway in 1960,

linking Brazil’s new capital to the resource-rich interior. Xingu National Park

was created in 1961 in an effort to preserve indigenous people’s way of life.

But the park was soon used as a pretext for a mass eviction effort by loggers,

ranchers, rubber tappers and miners moving deeper into the rainforest. Gold

miners on land claimed by Ximari put the Kayabí under increasing pressure to

leave their homes and arranged for two flights to transfer hundreds of

indigenous people out of the forests.

A view from above of the Parque Nacional do Xingu. Greenpeace

The families now living on land claimed

by Ximari say they are descended from more than a dozen Kayabí who went into

hiding in the forest for two months in the late 1960s after resisting attempts

to move them 300 miles from their home. Within a year they were joined by relatives

who made the eight-month journey back to Teles Pires from the national park on

foot.

Despite this the Mato Grosso

state land agency Intermat sold off vast swathes of land in the area in the

1970s and 1980s, in lots of 3,000ha of what it judged to be “empty land”. From 2006, federal prosecutors advised the

remaining Kayabí to occupy the areas they and their ancestors had previously

lived on so as not to lose their land rights.

Villages and agricultural spaces were set up

including on land claimed by Ximari, including a village called Aldeaia

Dinossauro from 2002 onward, and another called Aldeia Ximari. Dinossauro’s

founder told anthropologist Francisco Stucci the village had been built on the

site of his grandfather’s village. Only 2,100 people speak the Kayabí language

throughout Brazil, according to the Joshua Project, a Christian missionary

group, while only a few hundred are thought to live along the Teles Pires

river.

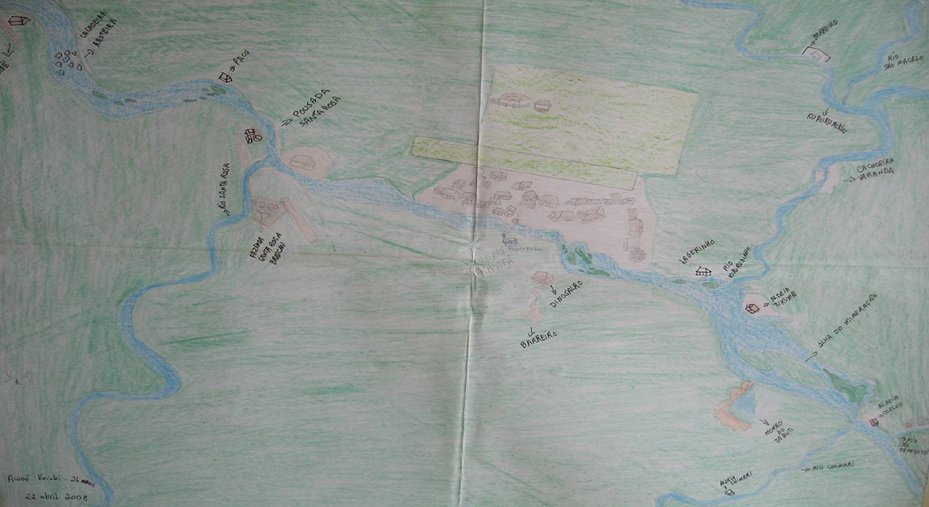

Hand-drawn maps sketched from memory by Kayabí people living on the Teles Pires, showing the location of Dinossauro village and the farm “Aldeia Ximari”. Dr Oliveira

Sacred spaces

The conflict with Ximari centred

on the sacred Lake Jabuti or ypi 'aweté, true lake, in Kayabí language. Locals

we interviewed said that Ximari employees visited the lake in

March 2022. They believe this was to

assess limestone mining deposits. The lake is on land known as the most

charcoal-rich and fertile, and the best hunting ground for wild pigs. Kayabí

elders are buried around the lake and a shaman, or spirit, is thought to live

in one of its caves.

“When I arrived here, it felt

like I was daydreaming,” a Kayabí man born in Xingu told the anthropologist Dr

Oliveira about the lake. “That’s the kind of place it is, very famous and very

sacred to us, because a lot of the things we respect are there.” He had grown

up hearing stories about Lake Jabuti from his grandfather and had returned to

the Teles Pires area at his request.

Both the identity of the Kayabí and their food

security is intrinsically tied to their close agricultural and spiritual

relationship with the land around the Teles Pires river, the anthropologist

argued. Youngsters are taught that when a kutap frog starts singing by the

river it is time to start sowing local varieties of banana, watermelon, corn or

manioc.

No species is more prized than the nut tree, which is highly

concentrated around Dinossauro and Jabuti but absent in Xingu, where some

Kayabí were forced to move. Nut milk is used to cook game, fish or porridge, or

as a hair dye. The nut tree’s lifecycle is used to mark the passage of time.

Clearing in Dinossauro village, with charcoal-rich “black earth” common to the Amazon basin. Dr Oliveira

National attacks

Indigenous people’s rights to

their ancestral land were enshrined in Brazil’s 1988 Constitution but are under

threat all over Brazil ahead of President Bolsonaro’s re-election bid in

October 2022.

A new constitutional

interpretation put forward by agricultural groups would require indigenous

people to prove they physically occupied contested land in 1988, at a time when

many groups had already been dispossessed and displaced. In June 2022 a Supreme

Court ruling on the case could set a precedent affecting ongoing land

demarcation cases for some 197,000 indigenous people occupying 11 million

hectares of land, including the Kayabí.

Bolsonaro is trying to rush a

series of laws through Congress which would put the Amazon and its inhabitants

more at risk than ever. Known as the

“destruction package”, the laws would give a wholesale green light to hundreds

of mining, logging, cattle and energy projects by removing protections for

indigenous people and their forest land.

Around 160,000km2 of Amazon

rainforest would eventually be swallowed up by mining projects if these laws

were to be successfully passed, according to the NGO Amazon Watch. It found

2,500 active mining applications overlapping indigenous land in November 2021,

covering an area nearly the size of England. Asset managers Capital Group,

BlackRock and Vanguard gave more than $14 billion in financial backing to the

mining groups who filed the licence applications noted by Amazon Watch.

An indigenous person takes part in a protest on the day of Brazil's Supreme Court trial of a landmark case on indigenous land rights in Brasilia, 15 September 2021. REUTERS/Adriano Machado

Overlapping legal attacks

The land claimed by Ximari was part

of a vast land area belonging to Kayabí communities, first established by

presidential decree in 1982. In 1999, after an anthropological survey showing

the Kayabí had historically been present there, alongside two other indigenous

communities, FUNAI stated that the borders of the area included both land in Pará

state and in Mato Grosso state, including the area claimed by the Ximari farm.

Despite this, the farm has

launched several parallel legal cases against the Kayabí for possession of the

land. Ximari’s attempts to annul indigenous claims to the land based on having

owned it since the 1980s was rejected in 2011 as both the court and FUNAI

considered the indigenous community’s rights pre-existent. Ximari appealed the

decision.

The Kayabí’s land borders were officially

registered by President Dilma Rousseff in April 2013, spreading across 1.05

million ha of land. Mato Grosso’s state government sought to annul Rousseff’s

land registration just seven months later, arguing the Kayabí did not live on

the full stretch of land attributed to them. Federal prosecutors and the

government’s indigenous administration body, FUNAI, both argue the land has

been historically occupied and owned by indigenous people.

Ximari launched a new

repossession case for the same land area in the federal court of Sinop in 2015,

arguing the Kayabí had used Rousseff’s contested decree as justification for an

“illegal invasion” onto the farm. The case was initially dismissed for being

too similar to a previous one the farm had unsuccessfully filed in 2007. After

an appeal, judge Kassio Nunes granted Ximari an injunction in a federal court

to remove the Kayabí people.

Judge Nunes has since been named

as one of Bolsonaro’s two appointees to Brazil’s 11-member Supreme Court and

has voted in favour of reinterpreting the Constitution’s indigenous rights

provisions.

Mato Grosso’s injunction to reverse the

registration process of the indigenous land was still under appeal by FUNAI and

by the federal government in May 2022. A conciliation process between the

indigenous community and the state had been postponed due to the pandemic.

Mining potential

Brazil’s national environmental

watchdog Ibama accused Ximari of carrying out illegal deforestation on small

patches of its land in 2019. The farm denied this in court filings and said the

deforestation had been carried out by the indigenous inhabitants themselves. Around

half of the farm was made up of legally protected land which cannot be

deforested, according to its registration documents.

Previous Ibama research has shown

more than 30,000ha of forest was deforested between 1995 and 2005 in the Mato

Grosso part of the Kayabí’s indigenous territory. A Birkbeck University thesis

on deforestation in the area based on satellite data analysis argues farmers

were responsible for this.

One reason Ximari may have been

interested in the land is mineral extraction. A man understood to manage Ximari’s

farm was listed as director of a local mining firm specialising in precious and

semi-precious gems, according to unofficial corporate data.

“It is the land that will guarantee our

culture,” a Kayabí leader was reported to have explained at a Supreme Court

hearing about the suspension of Rousseff’s demarcation case in 2014. “The river

is our market, the forest too. If we don’t have land, we’ll become

beggars.” In a letter delivered at the

hearing, another leader explained that Kayabí people’s absence from these lands

was caused by “deferred expulsion, maliciously devised”. He wrote: “Perhaps there were no Indians on

those lands in 1988, but there was certainly the memory of our ancestors”.

Farm sale

Court documents show the farm was

prohibited from being sold and was held as collateral by an Apiacas court in

August 2021 due to some unresolved issues described as “Tax Enforcement,

Enforcement Proceedings, Civil and Labour Proceedings”.

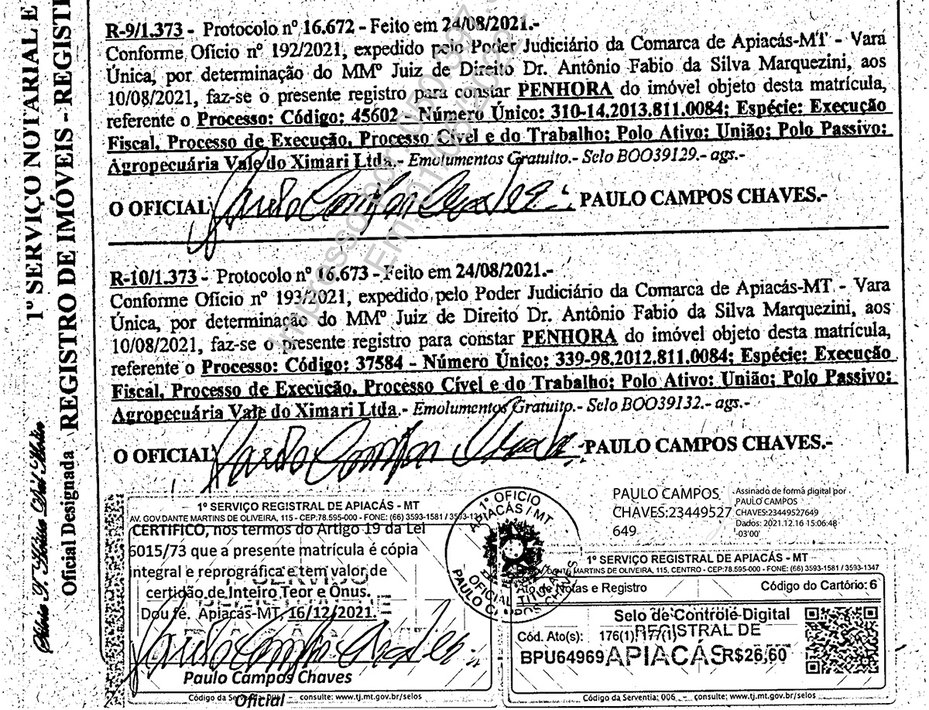

Extract from registration document, signed December 2021

Despite this Brookfield sold the

farm’s holding company Agropecuaria Vale do Ximari to an investor in January

2022, according to an update to the firm’s articles of incorporation in May

2022. Rio Tocantins Participações, a

Brazilian company, bought the business for R$12,983,954 (£2.16 million). The buyer filed documents to the Supreme Court

in May 2022 explaining it was aware the farm was within land demarcated for the

Kayabi indigenous group and wished to register an interest in the ongoing

dispute over the demarcated territory between the state of Mato Grosso and the

Federal government.

Brookfield said it “unequivocally refute[s] the

specific allegations of human rights abuses towards indigenous tribes” claiming

that these were “baseless allegations”. When pressed for evidence to

substantiate why it thought these claims were “baseless”, Brookfield did not

reply.

Brookfield Brasil, formerly known

as Brascan, has been linked to a whole host of other environmental and social

harms.

Newspaper reports from 1989

suggest the group has a long history of facing deforestation allegations. That

year a tin mine it jointly owned with British Petroleum was accused of

destroying at least 40% of the Jamari National Forest in Rondônia.

A World Bank report calculated

the mine had “affected” 90,000 hectares of this rainforest in western Brazil

due to mining, road clearance, soil dumping or river diversion, according to an

Ottawa citizen report. The Brazilian forestry service put this at 100,000

hectares, though Brascan told the newspaper the mine had not damaged more than

25,000 acres (10,117 hectares).

An undercover Sunday Times

reporter who was sent from London to visit the mine at the time wrote: “Inside

the security cordon, verdant-Amazonian rainforest is rapidly being transformed

into a moonscape of cratered, open-cast mines. Signs of dying forest are

everywhere (..) Not even scrubs grow, and no attempt has been made to repair

the damage by replacing topsoil and replanting.” Brascan said it had not

undertaken any reforestation work – and nor was it planning to.

Brookfield Brasil’s current-day energy projects

in Brazil also face a host of governance and environmental issues. A leak at a

hydroelectric dam owned by the asset manager’s Brasil branch may have been

behind floods that devastated the eastern city of Raul Soares in January 2020,

according to an

investigation by the Organised Crime and

Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP). The floods impacted 800 homes and left at

least 3,000 people homeless, according to February 2020 filings by a lawyer at

a public hearing.

The states of Bahia and Minas Gerais, in the northeast region of Brazil, suffer from floods that began in November 2021 and continue to wreak havoc in early 2022. Isis Medeiros / Greenpeace

The João Camilo Pena plant in

Minas Gerais state had been operating for more than a decade without an environmental

licence, according to the state prosecutor’s office. The company failed to

alert authorities in the city so people at risk from floodwater could be

evacuated, according to a technical report commissioned by the prosecutors. Brookfield denied responsibility for the

disaster, saying the plant was too small to have an impact on floods. The asset

manager said it was in the process of obtaining an environmental licence for

the plant.

The OCCRP has reported that

residents say they have been harassed by Brookfield employees for speaking out

about the impact of another Brookfield plant on their livelihood, the Barra do

Brauna Hydroelectric Power Plant. One protester says he and his wife received

death threats from Brookfield employees. State police opened two probes in

January and August 2019 into these alleged threats, according to files seen by us.

Brookfield’s subsidiary Elera

Renováveis said the protester had sued the company to obtain “an undue

financial advantage” after his compensation claim was rejected, and that he had