Last week we published the findings from our in-depth analysis of the world’s first open register of who controls companies. The Companies We Keep shows that two-years on the UK register of beneficial owners is having an important impact. One good example of this is the drop in rate of incorporation of one of the UK’s most widely abused corporate entities for money laundering, Scottish Limited Partnerships (SLPs). SLPs have been implicated in numerous money laundering scandals, and following their inclusion in the beneficial ownership regime in 2017, their rate of incorporation plummeted (see chart below).

However, our analysis also revealed that serious loopholes remain in the register and that could be exploited by individuals intent on keeping their association with companies hidden. The government and Companies House urgently need to address these issues if the register is to fulfill its potential. See more of our recommendations here.

New data, new challenges, new ways of working

This project was a first for Global Witness. We collaborated with volunteer data scientists from DataKind UK who helped us mine the register and find answers to key investigative and research questions. We took these insights to Companies House and used them to make the case for what needed to be improved for the register to fulfill its potential. This collaborative approach was really effective, and Companies House has already implemented some of our earlier recommendations and is now considering ways to implement the red flagging systems we developed. It is fitting recognition of the brilliant work of the team of volunteers that the project is also now a finalist for the 2018 DatSci Social Impact award.

There were three challenges we faced when we confronted the project: scale, reproducibility and the networked nature of the data.

A lot of data, not enough memory

First, the data was very large. With over 10 million records on companies, officers and beneficial owners, it far exceeded what a normal laptop can handle. We needed to use powerful cloud-based computers in order to store, clean and analyse the data. There is a mind-boggling array of relatively low cost options for cloud computing today. We chose to use a virtual machine on Amazon Web Services (AWS) with 122 GB of memory. This is is about 30 times more powerful than the average laptop with 4GB of RAM. These servers cost about $1 an hour to run on a pay-as-you-go basis. We would start them when performing computationally expensive tasks where we were required to handle all the data at once in memory and then just stop them at the end of the day.

Reproducibility

Second, we wanted to share our working with Companies House and other anti-corruption watchdogs keen who were also keen to monitor the data. We did this by publishing all the code we wrote to extract, process, clean and analyse the various datasets we used. This would enable anyone else to reproduce our working and build on top of it. If you’re interested in doing this, please fork our code!

Having our analysis as reproducible computer scripts also has the advantage that we can re-run our analysis and monitor the data at a later date and compare our results. This will be an important way through which we can understand if some of the issues we identified get resolved.

Everything is a network

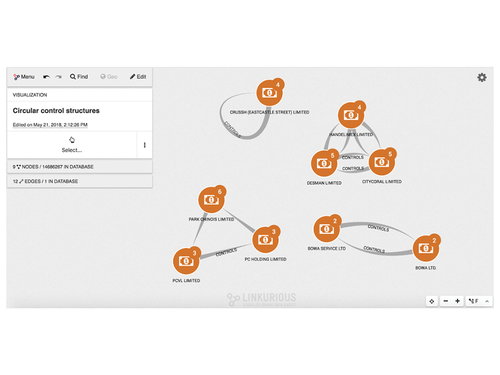

Third, we wanted not just to count records of specific types, but identify patterns. For instance, we wanted to be able to identify which companies controlled themselves via other companies or which companies were part of very complicated ownership structures. We addressed this by using so-called ‘graph’ database technology. Graph database technology helps researchers that want to understand connections in networks. We used two tools - Linkurious and Neo4J - that are becoming popular amongst tech savvy investigative journalists such as ICIJ.

How the collaboration with DataKind worked

The first stage of collaboration with DataKind began with a two-day event in November 2016, almost six months after the launch of the UK register. The event, organised in collaboration with OpenCorporates, Spend Network and OCCRP, was used to develop an exploratory analysis of the register.The insights and investigative leads generated that day were passed onto Companies House, which has since made changes to the register’s nationality field and age prompts, and looked further into 2,500 companies linked to secrecy jurisdictions. In 2017, the second stage of collaboration with DataKind began, involving a dedicated team of four volunteer data scientists working alongside Global Witness and culminating in the briefing published last week.

Civic tech and the importance of open source for collaboration

At Global Witness we want to embrace the open ethos of some of the most exciting investigative journalism in the last few years. Historically journalists have not been the most collaborative types, but investigative data journalism seems to be bucking this trend. Increasing numbers of media outlets are not only publishing the data that underpins their scoops but they are also publishing the source code that can help others to check, tweak and reuse their work in new scenarios. A growing list of open journalism initiatives is curated here and includes contributions from the likes of BuzzFeed, AlJazeera and The New York Times.

At Global Witness we’ve seen the value of sharing the technology you build first hand. Computer programs we developed to extract data from the Papua New Guinea register have been re-used and improved as part of an ambitious transparency initiative called PNGi which let’s users search and explore the connections between companies and political institutions. A similar story can be told about other open source investigative tech, such as Aleph which power data.occrp.org and is also used by extractives industry watchdog group, OpenOil.

Open data and the many eyes of the crowd

As we show in The Companies We Keep, it is essential that beneficial ownership data is published in an open format. While our report exposes issues with the UK’s register around verification and validation, we know that it is always riskier to lie in public than in secret. We also know that without the data being made available in an open format many of issues with the register that we identified would have remained hidden. On this project we’ve applied much the same principle to our working. We have published our source code on Github for others to review and build on. If you have any questions about any aspect of our analysis or work on this project get in touch with me on [email protected].