January 2019

The U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI), a key

regulator of oil companies drilling on federal land, is bracing for a “reorganization” that some predict will lead

to widespread resignations and undermine the agency’s ability to do its job. The

changes are enthusiastically supported by the oil industry, happy “that unnecessary barriers to oil and natural gas development are

minimized and eliminated.”

The DOI shake-up was

kicked off by former-DOI Secretary Ryan Zinke, who left at the start of 2019

following multiple ethics investigations.

But its architect is another Trump appointee who remains with DOI and has her

own problems: Senior Advisor Susan Combs. [2]

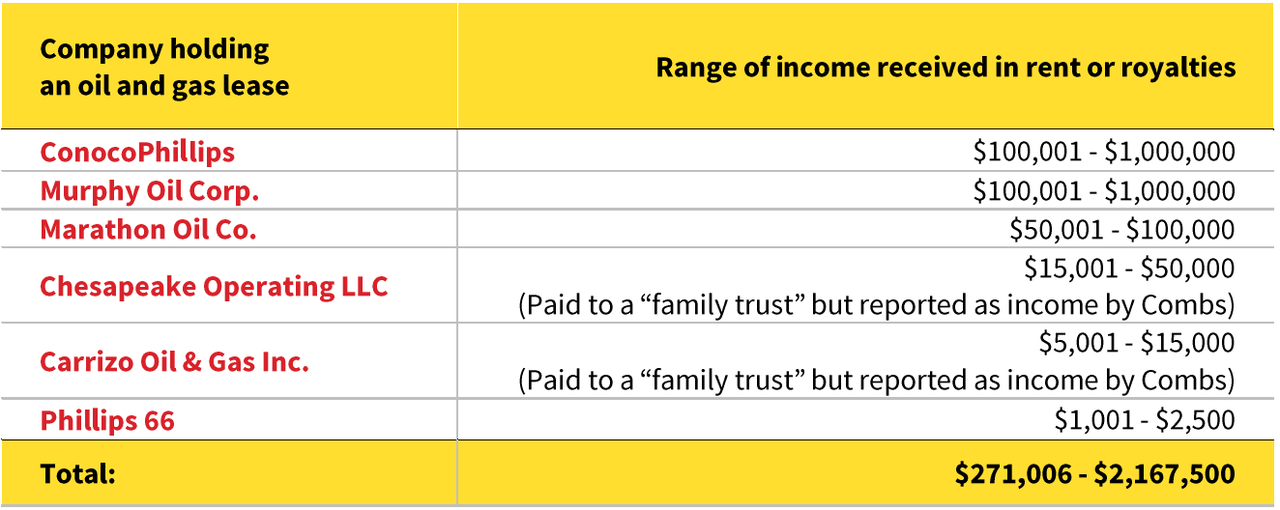

Combs owns a large ranch near the Mexico border and, according to her financial disclosure forms, receives income from leases she has issued to six oil companies. Between 2016 and 2017 alone Combs made at least $271,006 – and possibly up to $2,167,500 – from the drillers. Some of them, including ConocoPhillips and Chesapeake, are also big advocates of the DOI shake-up, heading the industry groups that publicly support it. They stand to benefit if DOI’s regulatory capacity over oil drilling is reduced thanks to the shake-up.

Combs’ apparent conflict of

interest requires that she step aside from DOI’s restructuring. Furthermore, the persistent conflict

allegations against Zinke, acting DOI

Secretary David Bernhardt, former-Environmental Protection Agency Director

Scott Pruitt, and now Combs show that U.S. conflict of interest laws need

urgent reform.

DISMANTLING THE INTERIOR

DOI is the federal agency responsible for managing natural resources on lands owned by the government as well as offshore, “including oil, gas, clean coal, hydropower, and renewable energy sources.” For these lands and oceans, DOI decides whether drilling licenses should be awarded, collects royalties, and sets environmental standards (a task the agency shares with the Environmental Protection Agency). As such, DOI is one of the government’s most important agencies regulating natural resource extraction, including domestic oil and gas drilling.

In January 2018, then-Secretary Zinke – who was a staunch proponent of President Donald Trump’s pro-oil “energy dominance” policy – announced that DOI would be “reorganized.” Zinke’s connection to big oil was no surprise: one of the scandals that dogged his time at DOI was a possible criminal investigation into a land deal between a foundation Zinke started and David Lesar, who chairs the oil infrastructure company Haliburton.

But while Zinke started the DOI shake-up, it has been led by rancher and former-Texas State Comptroller Susan Combs.

Susan Combs: Heads DOI shake-up, paid by oil companies. © Robert Daemmrich Photography Inc/Corbis via Getty Images

As Comptroller, Combs had a history of fighting federal regulations such as endangered species protections, famously likening them to “incoming scud missiles.” This included protections for little sandy lizards that Combs thwarted while claiming a victory for “jobs and the nation’s energy economy.” According to the Center for Biological Diversity and Defenders of Wildlife in Texas, the lizard is now “in danger of extinction or is likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future.”

A detailed plan describing the reorganization has not been released so it is not yet clear exactly what the new DOI will look like. DOI has stated it wants to “shift resources to the field” and “bring together employees” working across DOI’s several bureaus. Also, the headquarters and staff of four DOI bureaus may be moved to Western states, including the Bureau of Land Management, which administers federally-owned land and is responsible for awarding oil licenses on that land.

Additional statements by DOI may provide clues about the shake-up’s real impact. Zinke stated that he wanted to shrink the DOI budget by $1.6 billion and reduce the number of employees by some 4,000 people – eight percent of the full-time workforce – partly through staff “reassignments.” He also said that 30 percent of DOI employees are “not loyal to the flag.” However, DOI management insists that it “has no plans to run a Reduction In Force,” adding that some positions will be “vacated through voluntary retirements or moves to new roles.”

There are experts who have cautiously welcomed the current DOI shake-up, including Peter Schaumberg and Doug Wheeler, both of whom are currently with law firms that have represented big oil companies including ExxonMobil.

Schaumberg believes change is promising but “it will take more than simply reshuffling office locations to facilitate timely actions relating to development of the nation’s mineral and other resources.” Wheeler argues that, while the planned rearrangements might need tweaking, the process would be “an important step in the right direction.”

Other experts argue, however, that the changes will lead to large numbers of staff quitting, and may undermine the agency’s ability to do its job.

According to Amanda Leiter, currently at American University and a former Obama-appointed DOI Deputy Assistant Secretary, the agency shake-up is designed to encourage current staff to quit, “at great cost to DOI’s effectiveness.” Leiter concludes that the process has:

"no real intention of improving DOI structure and function but instead hopes to sow confusion, destabilize the department, and encourage staff departures."

Lynn Scarlett, a George W. Bush-appointed DOI Deputy Secretary, now with the Nature Conservancy, has raised similar concerns. And according to the Chairman of the House Committee on Natural Resources, Congressman Raúl Grijalva (D-Arizona):

"This reorganization is an exercise in weakening the Department of Interior by driving employees out. Once they’re gone, the extractive industries will be able to check off the top item on their wish list."

BIG OIL IS A BIG FAN

The DOI reorganization is predicted to drive out employees and destabilize the agency. © iStockphoto.com/pabradyphoto

Much like the oil lawyers who have supported the DOI shake-up, oil companies have also fully backed the effort. Industry groups that represent companies and lobby on their behalf have praised the process as a means of reducing burdens on the sector. The DOI website features excerpts of this support, including a “testimonial” from the Independent Petroleum Association of America (IPAA), which represents “thousands” of oil companies. According to the IPAA, the reorganization offers an opportunity to “reduce administrative redundancy and remove organizational barriers within DOI.”

The American Exploration & Production Council (AXPC), which represents 33 oil companies, has taken a similarly supportive position, as has Washington’s largest oil industry group, the American Petroleum Institute (API):

"We appreciate and support efforts to modernize and reorganize the Department in order to improve governance, streamline permitting and approvals, and improve coordination of government services so that unnecessary barriers to oil and natural gas development are minimized and eliminated."

Oil industry groups are not the only organizations that submitted testimonials reproduced on the DOI website. Three non-profit, pro-hunting organizations also provided comments: the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, American Wildlife Conservation Partners, and the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership.

FEELING A LITTLE CONFLICTED?

However, Global Witness research shows that oil companies’ support for the DOI shake-up creates a significant credibility problem for the process. Some of the same companies that think they will benefit from the changes have paid large sums in rent or royalties to the reorganization’s main architect, Susan Combs.

In April 2017, to be considered for a post at DOI, Combs filed a financial disclosure form listing her income over the preceding 16 months. This income, which was expressed in ranges and not precise amounts, included between $271,006 and $2,167,500 in rent and royalties from six companies. These payments were:

There is also evidence that Combs may still be receiving payments from oil companies. In July 2017, Combs also filed an ethics letter stating that “I receive royalties from Murphy Oil Corp., ConocoPhillips, Marathon Oil Corp., and Phillips 66 for the leasing of mineral interests that I own.” Unlike shares she held in Exxon and ConocoPhillips, Combs did not say that she would divest the royalty payments she received from these companies.

And the payments are not new. As Texas Comptroller, Combs was required to file financial disclosures, some of which have been published by the Texas Tribune. For the 2012 calendar year, Combs declared a minimum of $95,000 in royalties from oil drillers, including ConocoPhillips, Murphy Oil, and Marathon Oil. The year before, Combs declared at least $55,000 in royalties from oil companies.

Global Witness has also looked into the industry groups supporting the DOI shake-up and found that they are led by executives who work for companies that have put money into Combs’ pocket. Executives from ConocoPhillips and Marathon Oil both currently serve as Directors-at-large for the IPAA. At the same time, a Chesapeake executive serves as a Director for the AXPC, while a Marathon executive is both a Council Director and Council Executive Committee Member. And a representative from Phillips 66 has the role of Director and Finance Committee Chair with the API.

Each of these oil industry groups has submitted a “testimonial” to the DOI supporting the agency’s shake-up.

Federal ethics rules state that employees may need special authorization if a “business or financial relationship” is likely to raise questions about his or her impartiality when participating in government matters. In her July 2017 ethics letter, Combs pledged to adhere to this rule. In the case of oil companies that held her leases:

“I will not participate personally and substantially in any particular matter involving specific parties in which I know that any of these companies is a party or represents a party, unless I am first authorized.”

The U.S. Office of Government Ethics has cleared Combs for a post with DOI, stating that she was “in compliance with applicable laws and regulations.” It is not illegal for federal staff like Combs to lease private land to oil companies and Global Witness does not have evidence that either she or the companies have broken any U.S. laws.

In November 2018, Global Witness wrote to Combs asking whether she is still being paid by oil companies and whether payments she had received represented a conflict of interest. As of the date of publication, Combs has not responded. The companies that have paid Combs and the industry groups supporting DOI’s reorganization were also contacted but did not respond.

BRUSHING UP THE GOVERNMENT’S ACT

That Combs received payments from companies regulated by her agency may not be illegal, but the fact that she heads a shake-up of the agency that companies believe will benefit them does undermine the process’ credibility. To put these questions to rest, Combs should recuse herself from the process and the DOI Ethics Office and Congressional Natural Resource Committees should investigate whether Combs’ payments from oil companies may be unduly influencing her DOI duties, including reorganizing the agency.

But Combs’ case also highlights a trend that stretches to other Trump appointees, and shows how U.S. conflict of interest laws must be reformed. Zinke’s scandals, including his ties to David Lesar of Haliburton, are cited as a reason he resigned. Former-Environmental Protection Agency Director Scott Pruitt also reportedly left in part because of conflict allegations. And the new acting DOI Secretary, David Bernhardt, was a lobbyist for oil companies and has been described as a “walking conflict of interest.”

The non-profit watchdog Western Values Project maintains a list of possible conflicts for over 100 current and recent staff in DOI alone, accessible at departmentofinfluence.org. Such investigations and reporting show there is clearly a deep-rooted problem in the U.S. government, one that surely only worsens the public’s perception that corruption is rampant.

Global Witness believes that U.S. conflicts of interest laws should be strengthened to prevent officials with financial ties to companies from regulating, overseeing, or conducting other government business that affects those companies. Such reforms are necessary and long overdue and, given public concern about conflicts of interest in U.S. politics, these reforms should garner widespread support.

A good first step towards reform is the recently proposed For the People Act of 2019. The Act strengthens conflicts of interest laws and boosts enforcement by empowering the Office of Government Ethics. [3] Further reforms should prevent officials with financial ties to companies from making government decisions that directly benefit those companies After all, if loopholes in the conflicts of interest law remain, how can Americans be confident that the management of their resources is done in a way that benefits the public interest and not the oil and gas industry?NOTES

[1] Banner image © Raatzie/Getty Images

[2] As of the date of publication, Combs' full title is Senior Advisor Exercising the Authority of the Assistant Secretary for Policy, Management and Budget. Comb’s nomination to the post of Assistant Secretary, first submitted to the Senate in July 2017, has not yet been confirmed, due to concerns that DOI would approve offshore drilling near Florida. See Congress.gov, PN738 — Susan Combs — Department of the Interior; Congress.gov, PN1366 — Susan Combs — Department of the Interior; Roll Call, Holds on Energy and Environment Nominees Pile Up — Again, 22 January 2018.

[3] The 2019 For the People Act seeks to reform U.S. ethics rules and enforcement, including expanding the definition of lobbying, restrictions upon lobbyists entering public service, and increased capacity for the Office of Government Ethics. The bill would also require that the personal finances of the President and Vice President be more transparent. For additional information regarding the need for this transparency, see Global Witness’ December 2018 report on a Trump Organization hotel project in the Dominican Republic: A Foreign Affair.

Find out more

-

A Foreign Affair: Trump’s Dominican Republic Deal

Donald Trump is pursuing what appears to be a new business deal in the Dominican Republic despite pledging no new foreign deals – a deal which may be in violation of the U.S. Constitution.

-

Four signs the US is creeping towards a kleptocracy under Trump’s watch

If the past year has shown us anything, it’s that there’s been a blurring of the lines between the Trump Organization’s business interests, political decisions made by the administration and Congress, and how tax payer money is spent.

-

Global Witness welcomes Canadian regulator ruling on Glencore-controlled company and executives

The Glencore-controlled mining company Katanga Mining has today agreed to pay USD $22 million to settle allegations by Canadian regulators that it had failed to comply with disclosure requirements, including that it had not properly described risks of doing business with a controversial middleman in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).