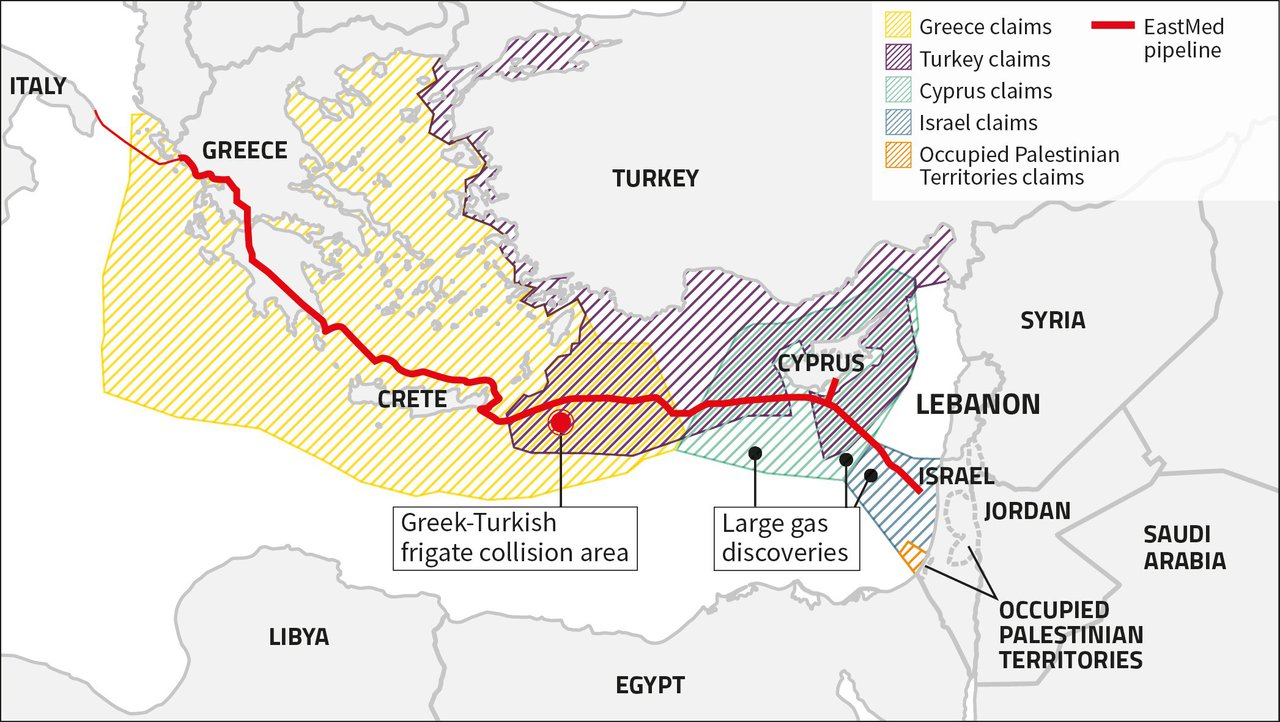

In August 2020, two warships – one Greek, one Turkish – crashed into one another off the east coast of Crete. Neither sank, and the collision was reportedly an accident. Yet despite being NATO allies, the two frigates were not on the same side. Instead, they were projecting power over a section of the Mediterranean – and its promised fossil gas reserves – claimed by Greece, Turkey, and Cyprus too.

That there is a risk of conflict between European countries and Turkey is unacceptable. More shocking, however, is that this conflict could arise over a resource – fossil gas – that will have little value if we are to halt the climate emergency.

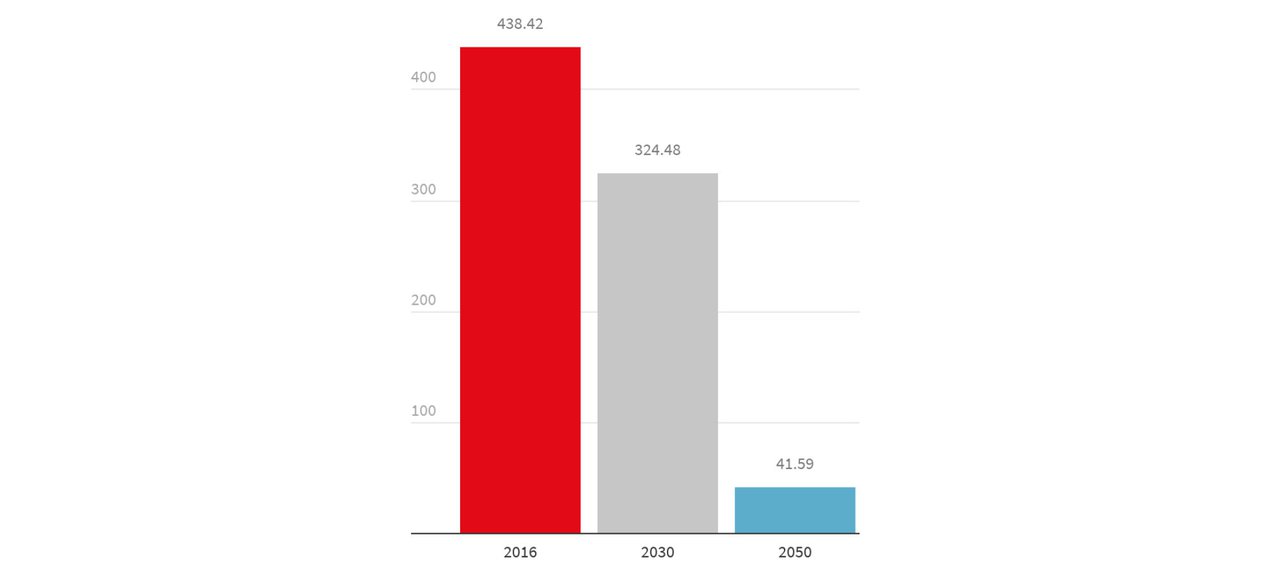

Today, the EU has enough gas to meet existing demand. And the EU predicts demand should soon decrease rapidly if it is to successfully fight climate change, shrinking 90 percent by 2050. EU countries do not need gas from the eastern Mediterranean.

At the same time, the gas over which Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, and the EU are fighting would produce an immense quantity of carbon dioxide. If only the gas already discovered in the disputed waters was extracted and burned, by 2050 it would produce almost as much as carbon as France and Spain together emit in a year.

Europe also does not need the proposed EastMed pipeline, which is currently supported by the EU as a “Project of Common Interest” despite crossing the disputed waters to bring gas from Israel. Were the pipeline to operate at full capacity until 2050, the gas it transports could produce more greenhouse gasses than a combined France, Spain, and Italy emit in a year.

It is critical that

tensions over gas in the eastern Mediterranean decrease immediately. The

clearest way to achieve de-escalation is for all parties to realize that they

cannot use the gas over which they are fighting and pledge to stop drilling. At

the same time, the EU should remove support for the EastMed pipeline and change

its law to ensure other gas pipelines do not get similar aid.

For full citations and calculations, see the dowloads section at the bottom of this page.

Gas and gunboat diplomacy

In the last 21 years, over 1,425 billion cubic metres (BCM) of gas has been found off the coasts of Cyprus and Israel – equivalent to nearly half of Texas’ proved reserves. This has led to a flurry of diplomatic manoeuvres resulting in swathes of the Mediterranean being claimed by competing countries. In 2011, Turkish-Cypriot leaders signed an agreement allowing Turkey to explore for gas in Cyprus’ exclusive economic zone, the government of which is headed by Greek-Cypriots. In 2019, Turkey also inked a deal with Libya claiming waters held by Greece and Cyprus, while in August 2020 Greece signed accords with Egypt and Italy mapping out their claims.

Not content to just draw lines on maps, in recent months those involved have sent their navies into the contested waters. In August, a flotilla of Turkish warships accompanied the Oruc Reis survey boat into waters claimed by Greece. In response, Greece and France also sent military vessels to the region. And when a Greek naval frigate approached the survey boat, it crashed into a Turkish frigate. According to the Wall Street Journal, a Greek official called the collision “an unfortunate incident that shows the risks of military brinkmanship.”

Fossil gas in the eastern Mediterranean: The claims of Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, Israel, and the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Locations approximated and are for illustrative purposes only

Tensions remain high. The Oruc Reis returned to port in September, but again entered disputed waters in October. Greece has put in an order for new French fighter jets while France and Cyprus have led EU efforts to sanction Turkey over its military manoeuvres. Also, the US has recently dropped its arms embargo against Cyprus and increased its naval presence in Greece. During a recent trip to Crete, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo even floated the idea of moving military assets from America’s base in eastern Turkey to the island.

The futility of fighting over gas

Cyprus, Greece, Turkey, and the EU need to find a peaceful solution to their border controversy. That NATO has set up a hotline between members Greece and Turkey is a promising step. Disputes between countries over who controls fossil fuels too often turn violent, with terrible civilian costs.

But conflict in the eastern Mediterranean would represent a particularly wasteful fight: if the climate emergency is to be tackled successfully the gas over which Europe and Turkey are jockeying cannot be used.

The EU does not currently need more gas. According to the data firm Artelys, the EU has sufficient supplies from Norway, Russia, Turkey, Central Asia, and North Africa to meet future demand. This is the case even if there is a year-long supply shock from one of Europe’s suppliers.

Just as important, the EU’s gas demand should also soon shrink dramatically. The EU has recognized that it must quickly reduce the gas it consumes to fight the climate emergency, which is having an unacceptable impact in both Europe and worldwide. Increased flooding in Europe has cost billions, while heat waves in India are becoming more frequent, killing thousands. And far from the clean image companies promote, fossil gas is a key driver of the emergency. In 2019, gas burned in the EU was projected to have produced more carbon dioxide than coal.

In 2018, the EU estimated how much it should reduce gas consumption if it is to play its part in stopping global temperature increases beyond 1.5°C of pre-industrial levels – the point at which the climate emergency will be catastrophic. By 2030, Europe needs to cut consumption by a quarter compared to 2016 levels, and by 2050 – when the EU promises to be “carbon neutral” – fossil gas usage must plummet by 90 percent.

EU’s predicted fossil gas consumption if global temperature rise kept to 1.5oC (billions of cubic meters, BCM)

This timeline is bad news for those who want to drill in the eastern Mediterranean. To date, only Cyprus has found gas near the waters that have caused tensions with Greece and Turkey. US drillers Exxon and Noble (which is now owned by Chevron), will start producing in 2030 and do so well into the 2050s, according to the oil and gas data firm Rystad. Counting only what has already been found, the companies are forecast to produce 304 BCM of gas by the end of 2050, the EU’s target date for reaching “climate neutrality.”

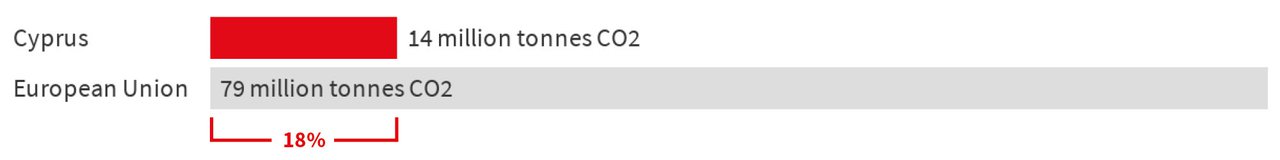

As shown below, Cyprus is unlikely to produce all of the gas it has found. Yet if it does, by 2050 Cyprus’ production alone could amount to nearly 20 percent of all the gas the EU can consume if it is to meet its climate targets.

Emissions from Cyprus’ gas in 2050 as share of EU gas emissions if climate goals met

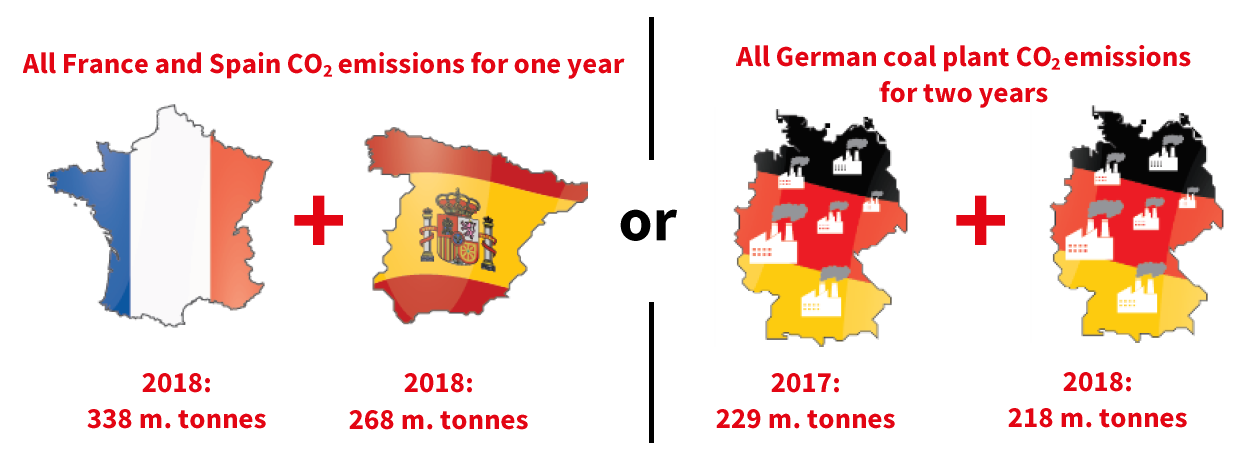

So much gas equates also with a lot of carbon dioxide. If burned, the gas produced by Cyprus between 2030 and 2050 would emit 577 million tonnes of carbon. In fact, this estimate is likely low because it does not account for emissions from the extraction, transport, or processing of the gas.

Yet even with this simple calculation, between 2030 and 2050 Cyprus’ gas would produce more carbon than all of Germany’s coal plants in 2017 and 2018 combined.

The fossil gas over which Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, and the EU are fighting is currently surplus to requirement. As EU demand plummets, this gas will only decrease further in value. It is critical that officials realize this before risking conflict in the region.

How Cyprus’ gas CO2 emissions between 2030 and 2050 compare

The EastMed pipeline could further raise tensions

At the same time, it is also critical that officials do not make matters worse. And the proposed 1,900 kilometre EastMed pipeline, which would cost €6 billion and carry gas from offshore Israel and Cyprus to Greece and into Europe, could do just that.

EastMed has been promoted by the premiers of Greece, Cyprus, and Israel, who in January signed a joint declaration of support. It is also backed by the EU, which has given the pipeline special “Project of Common Interest” (PCI) fast-track status. To date, the EU has promised EastMed up to €36 million in subsidies, and because of the pipeline’s PCI status it could receive more from the European Investment Bank. Construction has not yet started, although in April the companies behind it (the French-Italian EDF Edison and Greek DEPA) issued a €2.4 billion call for proposals to start work.

Turkey, meanwhile, has strongly condemned EastMed, as have Turkish-Cypriot leaders. The pipeline would traverse the same waters that Turkey, Greece, and Cyprus now contest. It would also compete with Turkey’s TANAP pipeline, which brings Azerbaijani gas into Greece and Europe. Responding to January’s joint declaration, Turkey’s Foreign Minister called EastMed “a new example of futile steps” to “exclude” Turkey and Turkish-Cypriots, which suggests the pipeline would further increase regional tensions.

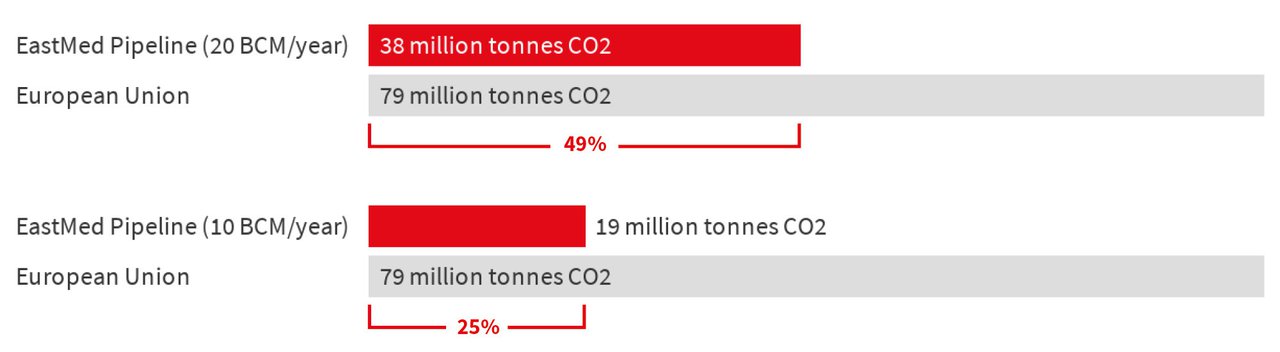

Again, this is not a fight worth having. According to its promoters, EastMed is scheduled to start operating in 2025 with an annual capacity of between 10 and 20 BCM. Pipelines can operate at less than full capacity. However, if EastMed does transport all of the gas it can, by 2050 the pipeline may have sent 500 BCM of gas to Europe. In 2050, if Europe is meeting its climate targets and gas demand has dropped to 42 BCM, an EastMed pipeline could supply nearly half of what Europe would consume.

Emissions from EastMed’s gas in 2050 as share of EU gas emissions if climate goals met

Were EastMed to fulfil this potential it would come at immense cost to the climate. Even with conservative estimates, the gas transported in one year could emit 38 million tonnes of carbon if burned. Pipelines also leak methane, which heats the planet much more quickly than carbon, and a pipe as long as EastMed would emit methane that equates with 365 thousand tonnes of carbon annually. In one year, gas and methane from the pipeline could produce more greenhouse gasses than the Bełchatów coal-fired power plant in Poland – Europe’s single largest fossil fuel emitter.

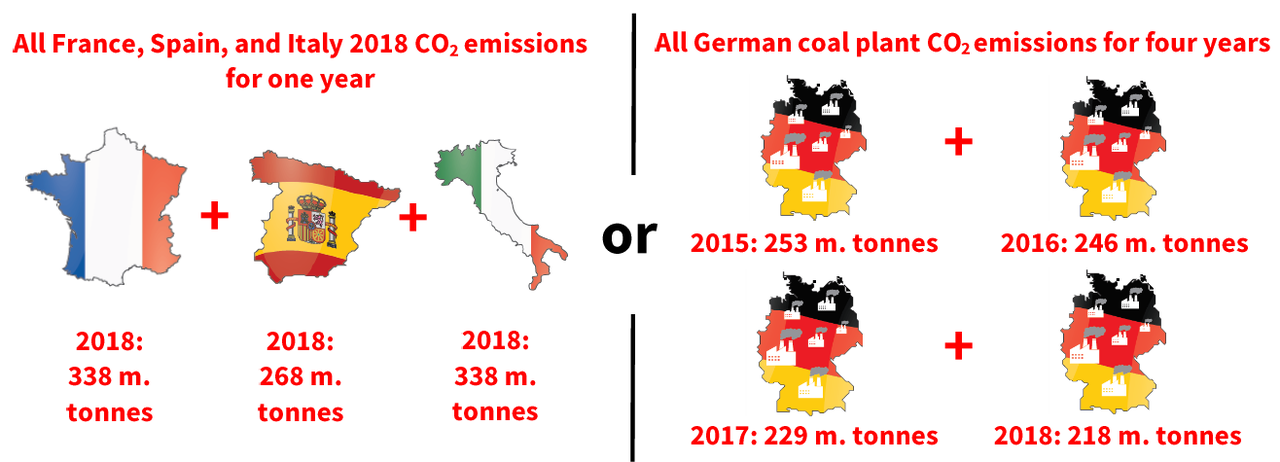

If EastMed operates at full capacity from 2025 to 2050, the damage would be much worse. During this period gas from the pipeline could emit 950 million tonnes of carbon if burned and methane that equates with 9 million tonnes of carbon. This would be more than all of Germany’s coal stations emitted in the four years leading up to 2019 combined.

These figures suggest that EastMed, like gas near Cyprus, is not needed and would come at great environmental cost. With multiple existing sources, it strains credulity to suggest that a €6 billion pipeline with so much unnecessary capacity is worthwhile. And as with the region’s gas, there is no reason for European countries, or Turkey, to raise tensions over a pipeline that could not be used.

How EastMed’s GHG emissions between 2025 and 2050 compare (at 20 BCM/year)

Conclusion

The immediate task confronting Cyprus, Greece, Turkey, and the EU is de-escalation. The best way to achieve this is for the parties to realize that the fossil gas over which they are fighting has little value without blowing a hole through efforts to curb climate change. Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey should not produce gas in the eastern Mediterranean and should pledge during negotiations not to allow drilling.

To ensure tensions do not increase further, the proposed EastMed pipeline should also be cancelled. Cyprus, Greece, and Israel should revoke their support for the project. At the same time, the EU should remove EastMed’s Project of Common Interest fast track status, preventing it from receiving further subsidies, including from the European Investment Bank.

And the EU should ensure that additional gas pipelines also do not receive regulatory preferences and taxpayer money. If the EU is to meet its climate targets it cannot afford to build more gas pipelines like EastMed. The European law – called TEN-E – under which support is granted to gas projects is currently under review by the European Commission. TEN-E should be changed to remove this support.

Fighting over fossil fuels is futile. It is now time to fight climate change.Endorsed by