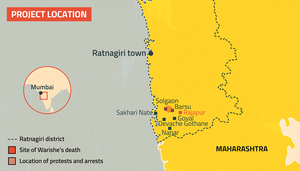

On India's Konkan Coast, 300km south of Mumbai, conflict over one of the world’s biggest new fossil fuel projects has led to hundreds of arrests and the murder of a journalist.

The Saudi-backed

scheme aims to build a combined oil refinery and petrochemical complex in a

rural district named Ratnagiri, famed for its fruit and fishing industries.

Communities and environmentalists have united to oppose the plans, fearing the

environmental impact and the consequences for local livelihoods.

No effort has been made to address these concerns, they allege. Instead, locals and activists have been criminalised, spied on, and forced into hiding.

A year ago, a journalist reporting on the controversy was killed, allegedly by a prominent supporter of the project who was on the refinery’s payroll. Furthermore, Global Witness has seen evidence that project proponents originally sought to develop the plans without the knowledge of local communities, potentially violating international standards on participation and consent.

Despite the fierce opposition, the Indian and Saudi governments recently announced a joint taskforce to push ahead with the plans.

“Our fight will be to the last... We want to tell the government that until now you have come with sticks and teargas, but if you want to make this happen, you will have to bring guns and bullets.” - Amol Bole, a community leader spearheading opposition to the project.

The village of Kasheli in Maharashtra, India, where journalist Shashikant Warishe lived with his family until he was killed in February 2023. Credit: Ashish Vaishnav / Global Witness

A relocated refinery

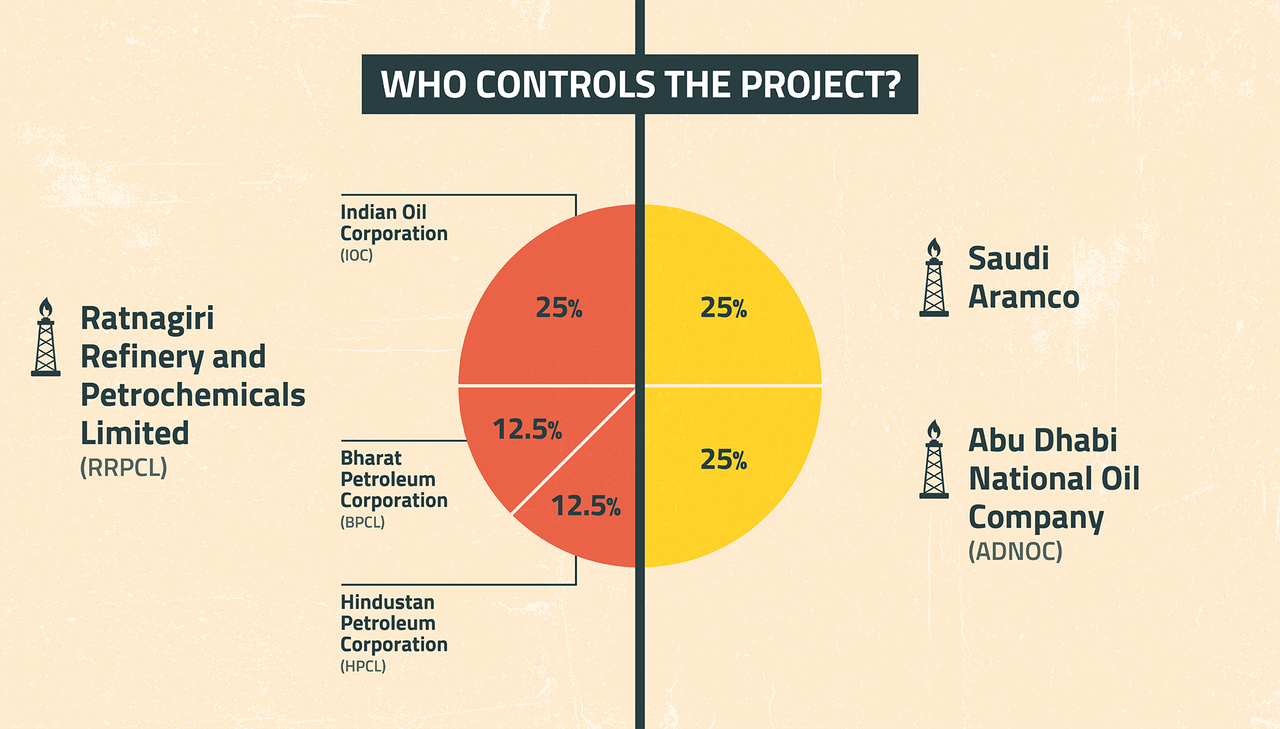

The project brings together oil behemoths from either side of the Arabian Sea. One half is split between Saudi Aramco and the UAE’s state-owned Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC). The other is divided among three Indian oil firms - the Indian Oil Corporation (IOC), Bharat Petroleum Corporation (BPCL) and Hindustan Petroleum Corporation (HPCL) – which, in 2017, formed a joint venture named Ratnagiri Refinery and Petrochemicals Limited (RRPCL).

In 2018, ADNOC and Aramco agreed to partner with RRPCL in the construction of a 60 million ton per annum oil refinery. Capable of processing 1.2 million barrels a year, this vast industrial complex was initially intended to cover 15,000 acres of land near a village named Nanar. However, opposition from locals blocked the plans.

Three years

later, officials from the state legislature met with village leaders from an

area 12km north of the original site. They told them of plans to relocate the

refinery nearby. Concerned about the potential impacts, local village councils – representing around 5,000 people from the villages of Barsu, Solgaon,

Goval, Shivane and Devache Gothane - passed

resolutions rejecting the proposals.

Fearing the authorities were planning to push ahead regardless, residents and environmentalists united under the banner Barsu Solgaon Panchkroshi Refinery Virodhi Sanghatana (BSPRVS): Committee to Oppose the Barsu-Solgoan Refinery. They were angry that the area had been set aside for the refinery project without any discussion with the communities that would be affected.

“No one was consulted about the decision to move the project here, the government kept us entirely in the dark.” - Kamlakar Maruti Gurav, a former council leader at Devache Gothane.

The murder of a local journalist

With tensions growing, a 48-year-old journalist named Shashikant Warishe began reporting on the controversy for a Marathi-language daily named The Mahanagari Times.

Journalist Shashikant Warishe of the Mahanagari Times, who was killed in February 2023 after reporting on local opposition to the refinery project

“He wrote extensively on the land acquisition fears of the villagers as well as the concerns of environmentalists,” Warishe’s editor, Sadashiv Kerkar, told the Indian Express last year.

On 6 February 2023, The Mahanagari Times published what would be Warishe’s last article. Riding home that afternoon, Warishe pulled his motorbike up to the curb to take a phone call. Minutes later, a jeep smashed into him, dragging his bike and body several metres along the tarmac before racing off. On-lookers rushed Warishe to hospital, but he died the following day.

Shortly after the crash, police arrested a 42-year-old man named Pandharinath Amberkar, a local businessman and well-known supporter of the refinery project. Soon after, they charged him with Warishe’s murder. The chargesheet cites Warishe’s journalism as the motive, noting that he wrote “constantly” in the paper about how the planned refinery project would destroy the livelihoods of local farmers. In particular, Warishe had accused Amberkar of seeking to profit from the refinery project by brokering land deals around the refinery site. This coverage had “angered” Amberkar, the chargesheet notes.

This hostility culminated with Warishe’s final article. In it, he comments on posters promoting the refinery that had been pasted around Rajapur, featuring photos of Amberkar and leading Maharashtrian politicians. “Who is in these photos with you?”, Warishe asks the politicians, calling Amberkar “a land-broker and accused criminal”.

Hours after these words were published, the police chargesheet alleges, Amberkar tracked Warishe down and crushed him beneath the wheels of his jeep.

Tied to murder

Amberkar’s direct links to the refinery company, RRPCL, are exposed in a new investigation by the Indian Express in partnership with Forbidden Stories, published simultaneously with this report. In December 2022, RRPCL paid a travel company owned by Amberkar 444,000 Rupees ($5431), pay stubs obtained by the Indian Express reveal.

Links between RRPCL and Amberkar stretch back long before that, Forbidden Stories and the Indian Express found: RRPCL Public Relations Officer Anil Nagwekar admitted to police during questioning about the Warishe case that he communicated with Amberkar since 2018, and that Amberkar's travel firm had provided vehicle services to refinery officials.

Left: the jeep that struck Shashikant Warishe on 6 February, with an RRPCL sticker. Right: Shashikant’s motorbike beneath the bumper of the jeep

Furthermore, at the time of Warishe’s death Amberkar was already facing criminal charges for injuring an opponent of the project with his jeep. In 2020, an anti-refinery activist was hospitalised for two weeks after Amberkar drove into him. Two years later, Amberkar was accused of attempting to smash open the head of another anti-refinery protester outside Rajapur Court. Both incidents resulted in criminal cases against Amberkar that remain open, with charges including criminal intimidation, voluntarily causing hurt by dangerous weapons or means, causing grievous hurt, and rash and negligent driving that endangers the life of another. Despite these precedents of violence directed at anti-refinery activists, RRPCL paid Amberkar's company to help them advance the project after he'd been charged, the Forbidden Stories and Indian Express findings show.

Indian Express and Forbidden Stories found no evidence that RRPCL or any of its commercial investors had authorised or incited the violence against Warishe or any other activist.

Much of this process was conducted opaquely, locals told Global Witness, in potential violation of international principles on participation and consent. According to commercial agreements held by Rajapur’s revenue office and obtained via Right to Information (RTI) requests submitted by activists, dozens of the land transactions which occurred within the project area were conducted before locals were informed of the plans in February 2021.

Yet, the decision to

relocate the refinery was taken long before this: in October 2019, a government

resolution seen by Global Witness authorised the state to begin

acquiring land for a large and as-yet unspecified project in the Barsu area.

Between the issuance of this resolution, and the initial meetings where locals

were first informed of the refinery plans, hundreds of acres of land changed

hands, in deals worth more than £1 million, according to an analysis of the RTI

documents that was shared with Global Witness.

The land grabs robbing people’s rights

As Warishe’s reporting had found, Amberkar’s principal involvement in the development of the project itself relates to the process of land acquisition. Documents obtained by Forbidden Stories and the Indian Express show that, between 2021 to 2023, Amberkar and his relative, Akshay Amberkar, were involved in at least 34 land transactions in villages located within the refinery project area, worth 28,300,900 Indian rupees (about $340,000 USD).

One deal seen by Global Witness shows Amberkar reportedly transferring land worth more than £2,000 to a trio of local journalists, in an attempt to “bait” positive coverage of the project, according to an investigation by local news-outlet Sprouts.

Activists and community members told Global Witness that Amberkar’s land-dealing around the refinery site was not solely aimed at personal profit, but formed part of a broader effort by project supporters to neutralize local opposition to the refinery. Further analysis by Forbidden Stories and the Indian Express identified a 200 per cent increase in land transactions in villages within the proposed project area between 2018 and 2022. Many of these transactions involved government-linked figures who could have had access to inside knowledge of the project plans, reporting by the Hindustan Times, which is supported in an analysis of land transaction documents that was shared with Global Witness by local activists, revealed.

As part of this scheme, activists believe that Amberkar and others sought to extract land from locals at a low price before selling it on to “investors” from outside Maharashtra. With no attachment to the local area, these investors – often government-linked figures with inside knowledge of major infrastructure plans – would happily sell on to the refinery for a profit.

“They wanted to make sure that when the deal is done and plans for the refinery are ready, there would be no opposition from landowners, because they would all be investors,” Satyajit Chavan, an environmental activist opposing the refinery project, told Global Witness.

Much of this process was conducted opaquely, locals told Global Witness, in potential violation of international principles on participation and consent. According to commercial agreements held by Rajapur’s revenue office and obtained via Right to Information (RTI) requests submitted by activists, dozens of the land transactions which occurred within the project area were conducted before locals were informed of the plans in February 2021. Yet, the decision to relocate the refinery was taken long before this: in October 2019, a government resolution seen by Global Witness authorised the state to begin acquiring land for a large and as-yet unspecified project in the Barsu area. Between the issuance of this resolution, and the initial meetings where locals were first informed of the refinery plans, hundreds of acres of land changed hands, in deals worth more than £1 million, according to an analysis of the RTI documents that was shared with Global Witness.

Refinery opponents claim that many of those who sold their land weren’t told it would be used for a large industrial project. This lack of transparency meant they both agreed to sell their land when they may not otherwise have done so, and accepted a far lower price than it would come to be worth – incentivising outside investors to participate in the scheme.

“They harassed poor people to grab their land and start the refinery project,” Kamlakar Maruti Gurav, the council leader from Devache Gothane, told Global Witness. “Farmers were being fooled to sell their land cheaply, they were told it would only be used for farming,” he claims.

At the same time, by failing to transparently communicate with and address the concerns of community members and other impacted stakeholders, and by instead seeking to advance the project without ensuring their informed participation in the process, RRPCL is failing to uphold international standards on business practice. These include the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, which state that “companies are expected to provide relevant information on their activities”; and the UN Guiding Principles, which require companies to “seek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships”.

Global Witness invited RRPCL and its commercial investors to comment on the consultation process failures but did not receive any responses. An ADNOC spokesperson told Forbidden Stories: “In 2018, ADNOC signed a Framework Agreement to explore a potential strategic partnership in the Ratnagiri refinery project, India. ADNOC has not been actively involved in the proposed project to-date.”

The repression of protests

Warishe’s murder outraged India, and fueled further opposition to the refinery project. Nevertheless, just two months later, in April 2023, officials sought to forge ahead with preliminary work in the project site.

The government deployed hundreds of police officers to the area. Immediately, they began making arrests.

“Police grabbed me on 22 April while I was on my way to Ratnagiri town from my home,” recalled Mangesh Chavan, a local environmentalist.

Satyajit Chavan was arrested on the same day; by the time they were released, four days later, they’d been charged with eight offences. The arrests followed police surveillance, Satyajit Chavan believes, in response to his activism on the refinery.

"My communications have been watched, I had to change my WhatsApp number because police were watching it... So we have fear: but now we’re here, we’ve come this far, we can’t go back.” - Satyajit Chavan, an environmental activist opposing the refinery project.

Environmentalist Mangesh Chavan, from the village of Juve just south of Ratnagiri town, was arrested and held without charge for four days, despite no prior involvement with the anti-refinery campaign. Credit: Ashish Vaishnav / Global Witness

Mangesh and Satyajit, both seasoned campaigners, were not the only people targeted. A further eight residents of villages within the refinery site were served with externment notices prohibiting them from entering the sub-district of Rajapur - close to the proposed refinery site - for more than a month. The notices were later overturned in Bombay High Court, but by then activists had been forced into hiding to avoid arrest.

Finally, police enforced a curfew and banned public gatherings in the area where land surveys and pre-construction ground testing was to take place.

But crackdowns on freedom of expression failed to have the desired effect. On 24 April 2023, hundreds of villagers marched to the project site. The next day, they blocked the road to prevent workers beginning land surveys and soil testing ahead of construction. Confrontations continued over the next few days, with activists alleging that excessive police force left several women injured.

"They hit us with batons, they grabbed women and dragged them across the hard ground, they threw teargas.” - Mansi Amol Bole, a female protester.

Protester Mansi Amol Bole, from the village of Shivane Khurd, says women were hit and dragged across the ground by police during demonstrations against the refinery. Credit: Ashish Vaishnav / Global Witness

Eventually, police locked down the zone, erecting roadblocks around a 10km radius of the refinery site and monitoring vehicles entering and leaving the area. Over five days, a total of 313 people were arrested and charged with criminal offenses, with as many 164 people included on a single chargesheet. A number of villagers were charged under the stringent and controversial Section 353 of India’s Penal Code, which punishes the use of assault or criminal force against a public servant. In 2017, the maximum sentence for this crime was increased from two to five years after a traffic cop was beaten to death while on duty; but its subsequent use against protesters has been condemned on two previous occasions. Following an outcry, the 353 charges were later dropped.

“It’s a way to harass people,” Ashwini Agashe, a lawyer who is representing the protesters, told Global Witness. “It’s a very costly process, some of them are working in Mumbai and have to miss days of work to come to Ratnagiri to attend hearings.”

An alarming picture

The repression of locals and activists in Barsu fits into a broader pattern of increasing pressure on environmental defenders in India. In 2023, a coalition of human rights groups expressed their concern at the risks faced by defenders in the country, in a letter to the UN Human Rights Council which highlighted “an ongoing pattern of repression of human rights defenders” occurring in a context of “rising authoritarianism and systematic erosion of the rule of law and independent institutions.”

Environmental campaigners in India also face severe risks, with Global Witness registering 81 killings of land and environmental defenders in the country since 2012.

The situation for journalists has also worsened in recent years, with the country falling eleven places to 161 out of 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index between 2022 and 2023.

“Indian journalists who are too critical of the government are subjected to all-out harassment and attack campaigns,” the press freedom watchdog said in its latest update on the country.

The traditional livelihoods under threat

The repression experienced by locals and activists in Barsu, however, has failed to diminish the ferocity of their opposition to the refinery project.

“They can put us in jail, we don’t fear it, we will keep fighting.” - Pratiksha Pawar, a local woman facing criminal charges after attending the April protests.

This determined

resistance reflects the close ties between people’s

livelihoods and the natural environment in Ratnagiri, where previous industrial mega-projects have been stalled by local

opposition. Over centuries, these livelihoods have shaped the area’s landscape and culture, from the world famous

alphonso mango

orchards to the fishing industry operating on its shoreline.

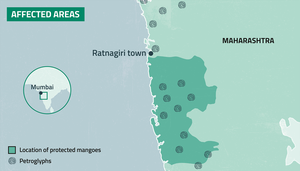

The Indian government has awarded a Geographical Indicator tag to mangoes that come from a specific stretch of Maharastrian coastline, between the towns of Ratnagiri and Devgad – precisely the area set to be transformed by the refinery.

“My family has worked in this for generations,” Kashinath Shantaram Gorle, a mango farmer opposing the refinery, told Global Witness. He worries that the refinery’s impact on local ecosystems and air and water quality will disrupt the specific growing conditions that make his crop unique, potentially destroying one of the area’s most important industries.

Down on the shoreline, workers in another of the area’s key industries also fear their livelihoods could be devastated by the arrival of the refinery, with Ratnagiri’s 103 fishery cooperatives employing almost 30,000 people also threatened by the project.

“If they build a port for this project, will they allow us to fish near it?” Majid Abdul Latif Govalkar, a fisherman from the village of Sakhari Nate, asked Global Witness. “No, because there will be a mooring point 20kms from the shoreline, there’ll be huge ships coming and going.”

Any terminal would block their sailing routes, Govalkar added, saying that currently he can sail from his fishing grounds to Ratnagiri town in three hours, but if a port were built, he predicts that this journey would take 10.

Fishing boats at rest

in the Kajali River estuary on the outskirts of Ratnagiri town, Maharashtra,

India. Credit: Ashish Vaishnav / Global Witness

Against these concerns that the refinery will decimate local livelihoods, RRPCL argues that the project will bring much-needed jobs to the area. Many young people already emigrate from Ratnagiri every year in search of work, helping Mumbai remain the world’s most densely populated city.

Such arguments are not without support within Ratnagiri itself. "Entire generations of young men and women have to go to Mumbai and Pune every year to make a living," Mr Pednekar, a small business owner in the town of Rajapur, told the BBC earlier this year. "Villages are being emptied out because there are no jobs. If we get the refinery here and it employs 50,000 people, the population will go up and it will help local businesses. Why should we resist that?"

But refinery opponents point out that few local people will benefit from employment in the refinery, which will require employees with high levels of technical education from big cities and abroad. Instead, they say, it will both directly displace traditional livelihoods and disrupt the broader ecosystems and fragile environmental balance on which they depend.

The fragile environment that would be transformed

The ecological fragility of Ratnagiri stems from the two principal ecosystems that frame it: the Konkan, a richly biodiverse stretch of tropical coastline; and the Western Ghats mountain range, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In 2011, a panel established by India’s Ministry of Environment and Forests issued a report on the ecology of the Western Ghats. It emphasized the area’s ecological sensitivity, warned against developing more industrial infrastructure, and urged the government to implement conservation measures.

Similarly, scientists have also emphasised the fragility of Maharashtra’s southern coastline, urging the government to adopt additional conservation measures to protect it.

“The Maharashtrian part of the Konkan is unique, with highly specialised conditions and so very special biodiversity,” Aparna Watve, coordinator for the Western Ghats with the international Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and a botanist studying the region for 25 years, told Global Witness. The region’s hard lateritic plateaus, rising above the Arabian Sea, burst into life and colour through four monsoon-soaked months every year; this kaleidoscope of plant life dies by October, and the rocky highland lies sun-cracked and bare for the rest of the year.

“Everything

is very adapted to these extremes in climate and terrain,” Watve explained, saying her research reveals “high local endemism”.

The RRPCL disputes concerns of environmental damage. “With the strict controls, there is minimal impact on the environment or the population or the crops which are grown in and around the area,” the company says on its website.

When asked about the proposed oil refinery, Watve said that she does not have access to relevant information on the final plan or environmental impacts of the proposed oil refinery and hence cannot give any final opinion on it.

“As a scientific community we have proven the sensitivity of the Western Ghats ecosystem over and over again,” she said. “Knowing this it, it is incomprehensible how a niche ecosystem will be able to take the brunt of proposed industry.”

Concerns over the refinery’s impact on local ecosystems are heightened by a broader weakening of environmental safeguards in India, several experts told Global Witness. “The Environmental Impact Assessment [EIA] process is being diluted, standards are being lowered,” said Parth Bapat, a Mumbai-based EIA specialist.

In 2020, five UN Special Rapporteurs issued a joint statement responding to proposed amendments to EIA processes in India, demanding an explanation of how the changes “correspond with India’s obligations under international law.” The Rapporteurs flagged a series of concerns, including a broadening of the scope for projects to be declared exempt from public consultation, and proposals allowing for the post-facto clearance of projects that commenced without obtaining the required environmental permissions.

They also criticised a series of adjustments to the timeframes governing compliance reporting, public comment, and public hearings, warning that they “make it more difficult for the public including those who may be directly impacted to exercise their rights to effective, equal and meaningful participation in environmental decision-making processes.”

Taken together, these changes risk violating human rights and environmental standards detailed in a series of international instruments, the Rapporteurs said, highlighting among others the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Declaration of the UN Conference on the Human Environment, the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

A number of environmental groups in India campaigned against the changes, with several enduring attacks including online surveillance, internet bans, and notices under India’s notorious anti-terror law – Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA). Eventually, the draft notification containing the changes expired without passing into law; but many of its most controversial elements, including those highlighted by the UN Special Rapporteurs, have since been slipped into effect in piecemeal fashion, principally through office memorandums issued by the environment ministry.

The ancient rock art that could be destroyed

Ecologists such as Watve are not the only specialists taken aback by the choice of site for the refinery. In the past decade, archaeologists have uncovered thousands of mysterious “petroglyphs” carved directly into the rock by an unknown people many millennia ago. This spectacular rock art depicts animals, humans, and encounters between the two: sharks, fish, a stingray, birds, a lizard depicted from below, an elephant whose torso is filled with ninety smaller carvings; people with their arms locked above their heads, framed by straight lines and swirling patterns. In one vivid scene, a person appears to be holding apart two giant leaping tigers, in an apparently ancient approximation of the Master of Animals motif.

Villager Kamlakar Maruti Gurav points to an ancient petroglyph carved directly into a rocky plateau outside the village of Devache Gothane in Ratnagiri district, Maharashtra, India. Credit: Ashish Vaishnav / Global Witness

Archaeologists

place the etchings at between 10,000 and 40,000 years old, pointing to several

indicators of their age: the absence of bulls or other livestock, suggesting they

predate agriculture; a carving of a hippo, not seen in the region for 12,000 years; and the presence of microliths, or

small stone tools, generally dated to the Mesolithic period.

While thousands of glyphs have been found along 300km of the Konkan coast, “Ratnagiri has by far the greatest concentration,” says archaeologist Sudhir Risbud. His team has documented 200 geoglyphs in the proposed refinery area that could be impacted by the construction plans. Two clusters of the artworks form archaeological sites that have been nominated for UNESCO World Heritage status.

“We’re not against development,” Sudhir emphasised. “But communities here are concerned that they’re not implementing development properly. There’s so much of importance here, creeks, the fishing industry, vital water reserves for the whole area. They have failed to take a broad perspective on the impact of the project and the significance of the local area.”

The demand for oil

The Indian government is backing the project amid steep projected increases in India’s oil demand. A burgeoning population and rapid economic growth will spur increased demand from key sectors, the Economic Intelligence Unit predicts, including passenger cars, goods transportation and aviation. In this context, ministers frame RRPCL as vital to India’s future energy security.

In the wake of April’s protests, Maharashtra’s Industries Minister announced that the state government would move forward with the project only after winning the confidence of local people. Such commitments seemed to have been forgotten by September, however, when India’s central government restated its determination to build the complex. According to India’s Ministry of External Affairs, Saudi leader Mohammed Bin Salman and India’s Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, agreed to establish a taskforce to accelerate the process.

However, energy experts warn that a project of this scale undermines India’s net-zero commitments. Though unlikely to be operational before 2029, it could release 177 million tonnes of CO2 a year, roughly equivalent to the annual emissions of the Netherlands or Argentina.

“1.5°C compatible scenarios require a phase-out of fossil fuels by 2040 for India,” Nandini Das, an energy economist at Climate Analytics, told the India-based outlet Climate Fact Checks. This echoes a broader scientific consensus, voiced by the UN and IEA, that developing new oil and gas fields is incompatible with a 1.5°C temperature rise.

Conflicts of interest

Staying below a 1.5°C temperature increase remains a key goal of COP, the annual UN climate change conference, with COP28 taking place in the UAE.

The conference’s President, Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber is the CEO of ADNOC - one of the biggest investors in the Ratnagiri refinery project.

Al Jaber presided over a controversial Presidency, claiming at one point that there was “no science” to show that a phase-out of fossil fuels was necessary to combat climate change and that attempts to do so would “take the world back into caves”. He later rowed back on the statement, claiming it had been misrepresented and that a phase-out was “essential”. Eventually, the final COP28 statement saw 198 countries agree to “transition away” from fossil fuels – the first time fossil fuels have been explicitly mentioned in a COP agreement. However, it fell short of calling for a “phase-out” or even “phase-down” of their use, a key demand of climate-vulnerable countries at the summit.

As CEO of ADNOC, however, Al Jaber himself shows little sign of “transitioning away” from fossil fuels – let alone phasing them out. Indeed, RRPCL’s huge potential refining capacity aligns neatly with ADNOC’s broader plans to massively ramp up fossil fuel production. Global Witness analysis of industry data shows that ADNOC is aiming to produce 1.25 billion barrels of oil equivalent in 2030, an increase of 42 percent on current levels. Conversely, the UN Environment Programme says that global emissions must be reduced by 45 percent by 2030 if limiting temperature rises to 1.5°C – which Al Jaber claimed was a “top priority” of COP28 – is to remain possible.

If built in line with original plans, RRPCL could refine much of ADNOC’s additional crude oil production. Its capacity of 1.2m barrels a day – 60 million tonnes per annum - could handle almost a quarter of ADNOC’s planned 2030 production capacity. The President of COP28, then, is heavily invested in the world’s biggest new fossil fuel project – and set to lose billions of dollars if it doesn’t go ahead.

Such a conflict of interest at the heart of global climate talks is a particular concern for villagers in Ratnagiri. Studies have repeatedly highlighted India’s vulnerability to climate change. The World Bank has warned that destabilisation of the monsoon cycle “could precipitate a major crisis, triggering more frequent droughts as well as greater flooding in large parts of India.” Coastal areas are particularly at risk, as “sea-level rise and storm surges” could contaminate drinking water and spur a fresh wave of cholera epidemics, it added.

Ratnagiri is especially vulnerable. Over 48 percent of its coastline is under high risk of flooding, a 2021 study showed. Since 1978, high tide levels in Ratnagiri have risen by six centimetres, causing erosion of the beaches and damage to estuaries and flatlands. Out on the Arabian Sea, cyclonic activity is already intensifying, generating rains and winds that amplify flood risk throughout the west of India.

The silencing of defenders

Ratnagiri villagers, then, find themselves on the frontlines of the climate crisis. Their position places them in the eye of debates setting the urgent need to tackle global heating against the imperative to ensure a reliable energy supply in one of the world’s fastest growing economies – one with minimal historic responsibility for the emissions that caused the crisis.

But their voice in this debate is being silenced. Global Witness calls on the Indian government and project developers to ensure that the communities’ rights are upheld and their relationship to their land and environment is respected.

Recommendations

- The Indian government and RRPCL must follow international standards in the development of large-scale infrastructure projects, including ensuring that affected communities are informed throughout their evolution and that key processes such as land acquisition are not initiated without their knowledge.

- Project developers must ensure research on a project’s likely impacts, both social and environmental, is reviewed and evaluated by specialists and shared with affected communities, so they are able to take an informed position on the project.

- The government must respect fundamental rights to freedom of expression, assembly, and protest, and refrain from using legal instruments to silence or intimidate those voicing legitimate concerns about industrial projects that will impact them.

- The government must ensure its environmental impact assessment procedures are in line with international standards, taking into account the recommendations made by UN Special Rapporteurs in 2020, particularly on ensuring the participation of and consultation with affected communities.

- The government must prioritise a genuine, just and rapid transition away from fossil fuels to renewable energy technologies.

- Fuelling oppression: Download the full report as PDF (English) (635.6 KB), pdf

- Fuelling oppression: Read the report in Hindi (660.6 KB), pdf