Major international brands sourcing palm oil from Brazilian plantations linked to violence, torture and land fraud

Nova Betel Quilombola community member who prefers not to be identified in house allegedly burned by BBF’s employees. Karina Iliescu

Urgent action is needed by international companies and the European Union to address escalating conflict, violence and harms against Indigenous and traditional communities living with palm oil production in Amazonian Brazil.

Alongside the wide Acará river, in the Amazonian Brazilian state of Pará – the country’s largest palm oil producing region – claims of violence, land grabbing and the forced eviction of Indigenous, Quilombola, riverine and campesino communities has been a constant reality. Conflicts in Pará have become longer and deadlier for land and environmental defenders since the beginning of President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration, and especially since early 2022, when public opinion polls started to suggest an electoral defeat for him.

Later this year, Brazilians will head to the polls to select their new president. Voters will have to decide whether to endorse another term for the incumbent, Bolsonaro. According to traditional community leaders, the pre-election message from ‘deputies and government officials’ to local palm oil producers is clear: “execute those who are protesting and creating problems until the end of 2022.”

Two Brazilian palm oil giants in particular, Brasil Biofuels (BBF) and Agropalma, are embroiled in long-standing conflict with local communities. BBF are accused of waging violent campaigns to silence Indigenous and traditional communities defending their ancestral lands, while Agropalma is linked to fraudulent land grabs and stranding or evicting communities. Both companies have acquired these lands to grow profitable palm crops, apparently at the expense of communities’ constitutional rights.

Agropalma states that its corporate policies forbid actions inhibiting legal and regular activities of Human Rights Defenders, while maintaining Agropalma’s right to protect its employees and its assets. Agropalma denies using violent actions against the communities and individuals in this report, and states that there are no land claims by Indigenous people overlapping with Agropalma lands.

BBF acknowledges the existence of an ongoing conflict in the region, which it claims it is trying to solve. The company believes it is rather the victim of criminal actions against its employees, which BBF has reported to the police. BBF denies causing or intending to cause physical harm to community members. It stated that its hired armed security is instructed to act peacefully, respectfully, and in accordance with current legislation. Further detailed responses are included below.

Vila Gonçalves is isolated by Agropalma’s palm plantations. Cícero Pedrosa Neto

Major international brands – ADM, Bunge, Cargill, Danone, Ferrero, Hershey’s, Kellogg, Mondelez, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Unilever and others – continue to purchase palm oil from BBF and/or Agropalma despite the situation in Pará, contributing to the violations of Indigenous and traditional peoples’ rights. Companies’ responses are included below.

There is an urgent need for BBF, Agropalma and all companies purchasing palm oil from them to take action to address ongoing conflict and prevent any further attacks and harms against Indigenous and traditional communities living with the violence associated with palm oil production in this region. This includes withdrawing armed security guards and ensuring that BBF and Agropalma’s employees and contractors act in accordance with the law and that they do not in any way threaten the safety and security of the communities.

Further, governments of key consumer markets must take action to hold companies accountable under existing laws as well as by adopting new laws. For example, landmark proposed European Union (EU) legislation mandating corporate human rights and environmental due diligence must be strengthened and implemented as a priority.

Palms in the forest

In the mid-to-late 2000s, Brazil’s federal government incentivised the development of palm oil in Pará. The resulting boom in palm oil, called ‘azeite de dendê’, is today largely used in the food and biofuel industries. Palm plantations in Pará currently cover 226,834 hectares, an area almost the size of Luxembourg – much of which used to be rainforest.

Two Brazilian companies dominate the industry locally – Agropalma S/A and Brasil Biofuels S/A (BBF). Although competitors, both have reportedly carried out brutal actions against traditional peoples who for centuries have been living and using ancestral lands that are now adjacent to and overlapping with palm plantations. Brazil’s constitution protects Indigenous and Quilombola communities’ rights to their ancestral lands.

Agropalma and BBF both recently announced ambitions to invest heavily in their palm oil plantations. The reality for communities strangled by their plantations is a nightmare.

BFF's violent conflict

BBF reports that it is the largest producer of palm oil in Latin America with over 80% of its plantations in Pará. Its production there amounts to approximately 200,000 tons of oil per year, over a third of Brazil’s total production.

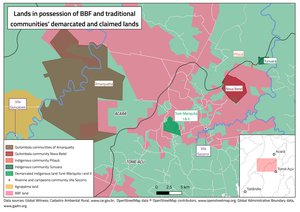

BBF’s Pará holdings are mostly located in the Acará/Tomé-Açu region, neighbouring the demarcated Indigenous lands of Turé Mariquita I and II of the Tembé Indigenous people. They are also neighbouring lands claimed by the Turiuara and Pitauã Indigenous peoples and overlapping with lands claimed by the Nova Betel ‘Quilombola’ (communities of descendants of escaped slaves), the Quilombola communities of Turé, Vila Formosa, 19 do Maçaranduba, Monte Sião, Ipatinga-Mirim and Ipatinga-Grande (together forming the association Amarqualta, Associação de Moradores e Agricultores Remanescentes de Quilombolas do Alto-Acará), the riverine and campesino communities of Vila Socorro, and other smaller campesino communities.

Since the beginning of 2022, land conflicts in the

area have escalated. In April 2022, armed men allegedly hired by BBF threatened to burn alive the sister

of a Tembé Indigenous leader, Paratê Tembé.

I have been threatened…Strange cars follow me to different places, including to my house. BBF’s employees tell me that they are going to kill me [and] my family. - Paratê Tembé, 2022

Edvaldo Santos de Souza, a

Turiuara Indigenous leader, regularly speaks out about the threats. “BBF’s employees wearing the company’s uniform stopped

me several times to tell me I should be careful and look where I am going,” he

states.

Many of the claims made by communities have been

supported by the Pará State’s Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPPA) and Brazil’s

Federal Prosecutor’s Office (MPF).

In March 2022, the MPF issued a statement

that BBF’s plantation areas overlap with claimed Tembé areas undergoing

demarcation by Brazil’s Federal Indigenous Affairs Agency (Funai), and that BBF

breached agreements with the Indigenous people previously made by the company

it acquired, Biopalma da Amazônia. Without a buffer zone, the Indigenous,

Quilombola, riverine and campesino communities say BBF palm plantations are strangling

them. The buffer zone should be at least ten kilometres wide, according to the MPF.

This situation is worse for unrecognized Quilombola communities whose lands have not been demarcated. “It’s absurd! Day and night they approach us in our territory, they approach us at our doors, they block our roads... Our security is compromised by the fact that our land is not demarcated,” states a member of the Nova Betel Quilombola community.

Indigenous and Quilombola community protests against BBF in front of a court in Tomé-Açu. Karina Iliescu

A litany of abuses

Global Witness received information of continued abuses in late April 2022 and early July 2022, attributed to armed men alleged to be working on behalf of BBF.

- Groups of armed men have blockaded multiple roads around Indigenous, Quilombola and riverine territories.

- Armed men have been stopping and searching cars and people on motorcycles saying they are ‘on the hunt’ for Indigenous and Quilombola leaders.

- Armed men have tortured detained members of an Indigenous community by spilling burning plastic over their backs.

- Armed men have shot and injured at least one Indigenous community member; several have been made to lie down, humiliated and had shots fired near their heads.

- Armed men forced a Quilombola man and a teenager who were working on their crops to lay on the floor, firing shots next to their heads, causing both serious hearing problems.

- Daily and nightly, community members are stopped, questioned and humiliated by BBF employees and/or security men.

Global Witness was in the region when some of these incidents occurred and heard directly from community members what took place. “They [armed men] left their big cars, with other men who were wearing BBF’s uniforms, shooting at all of us. They wanted to scare and certainly hit us,” laments an Indigenous community member. “Every single day is a different humiliation; people are being tortured here! We are exhausted. We live in a war zone. Luckily my friend hasn’t died from the shot that hit him, but I’m not sure how lucky other people will be when this happens again. I am sure this will happen again.”

BBF has filed over 550 police reports against community members in what the Indigenous Tembé lawyer, Jorde Tembé Araújo, calls “attempts to criminalise the protests of the Indigenous and Quilombola peoples.” The MPF concurs.

"We don’t want to fight with them anymore. We want them far from us. They torture and kill us, and, in the end, we are the ones who are criminalised by society." Edvaldo Santos de Souza, Turiuara Indigenous leader, 2022

A statement given to the police by an outsourced security guard working for BBF describes how the company instructed its workers to create false allegations of theft and other crimes, seeking to incriminate Indigenous peoples. After being reminded that he was under oath, the security guard confessed that he “was not able to know if the theft was committed by Indigenous persons” and he “could not identify if they were armed”. He only said these things because the “company told him to” and he was “afraid of losing his job.”

The violations reported to Global Witness have led some community members to no longer believe in co-existence with the palm companies. Contacted in April 2022, BBF acknowledged the existence of an ongoing conflict in the region, which it claims it is trying to solve. The company believes it is a victim of criminal actions against its employees, which BBF has reported to the police. BBF denied causing or intending to cause physical harm to community members. It stated that its hired armed security is instructed to act peacefully, respectfully and in accordance with current legislation.

BBF brought chaos since they started here, but this year things are even more dangerous, I am afraid people will die and I am worried they might kill my family and friends. - Nova Betel Quilombola community member, 2022

Global Witness contacted BBF again in September 2022 with more detailed allegations. BBF responded claiming that certain incidents in April 2022 such as the alleged destruction of its Fazenda Vera Cruz headquarters resulted from the “criminal actions” of Indigenous and Quilombola members, including vandalism and arson in retaliation for the company’s interception of palm fruit that the company alleges was stolen by the communities. Jorde Tembé Araújo, a legal representative for the Tembé indigenous community, affirms that the alleged damage to Fazenda Vera Cruz happened in a moment of mutual conflict and could have been provoked by either parties involved, community members or BBF. The communities maintain that their action was in response to BBF’s seizure of palm fruits from the communities – legitimately grown on a small scale on community (not BBF) lands – and the company’s alleged use of live ammunition fire against community members, as reported by media at the time.

Elias Tembé, Turiuara Indigenous leader. Karina Iliescu

Community leaders interviewed by Global Witness about this and other BBF claims in response to this report acknowledge that a few members of communities – who they say do not represent the interests of the majority – do attempt to fight back against BBF’s alleged violation of their rights. BBF also attributed various incidents against their property and employees to an individual, Adenísio dos Santos Portilho. This individual, from a community self-recognised as Turiuara, may be facing potential criminal charges. Indigenous and Quilombola community representatives interviewed by Global Witness state that he does not represent their communities, and they do not condone his alleged actions.

Video and photo evidence related to these and other incidents supplied by both BBF and the communities, and reviewed by Global Witness, suggests that while there is violent conflict involving both sides, on balance, BBF employees and persons acting for BBF appear to greatly outnumber Indigenous and Quilombola community members and have indeed carried out violent attacks against them.

Agropalma, fraudulent land grabs and stranded communities

If you take a winding dirt road from Tomé-Açu and you cross the Acará-Tailândia ferry, you will see palms stretching as far as the eye can see. But it is another big palm oil company who dominates the landscape.

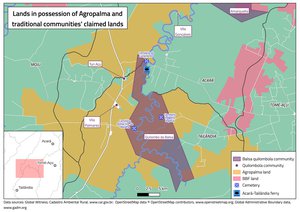

Agropalma has been operating in the Pará region since the 1980s. The palm oil company is part of the powerful Brazilian bank and company conglomerate, Alfa Group. With revenues of R$1.4 billion (approximately US$ 270 million) in 2020, it can produce around 170,000 tons of oil annually, mostly for the food and the cosmetics industries, which it intends to increase by 50% until 2025.

The company controls 107,000 hectares of land, the size of 150,000 football pitches, in the region of Tailândia. Agropalma’s plantations and legal reserves allegedly overlap with lands claimed by the Quilombola communities of Balsa, Turiaçu, Vila do Gonçalves and Vila dos Palmares do Vale Acará (that together form the association ARQVA). Agropalma acknowledged to Global Witness that almost all the lands that ARQVA is requesting overlap with their legal reserve holdings. However, it maintains that no Indigenous people’s claimed land overlaps with Agropalma’s plantation areas.

Agropalma has been accused of acquiring land with illegal titles where thousands of traditional, Indigenous and Quilombola peoples historically lived and from which they have been removed. These issues are alleged to have been ongoing for almost 50 years, according to legal papers filed by MPPA.

Raimundo Serrão is 62 and a Quilombola resident of Vila dos Palmares. His parents were descendants of formerly enslaved people escaping debt bondage who migrated to Acará’s river bay in the early 1900s. That area is now in Agropalma’s possession. “After years of a happy life by the river bay, a land grabber who was planning to sell our land to Agropalma entered our house with three other armed men offering a small amount to my father in exchange for the land … This happened in the late 1970s,” he recalls. “If we hadn’t accepted the deal and left, land grabbers and their henchmen would have killed us all.”

Responding to Global Witness, Agropalma stated that it does not support the behaviour and practices alleged in Raimundo Serrão’s case, citing policies requiring a rigorous analysis of the legitimacy of Agropalma’s land use. The company further states that it recognizes and respects the right of traditional communities and Indigenous peoples to their lands and does not occupy these area.

Many such communities were subjected to land grabbing that

expelled the historical owners of the land, thousands of hectares of which were

later acquired by Agropalma. Brazil’s courts and prosecutors have recently made

findings of fraudulent acquisition of land in Pará, following cases brought by

MPPA contesting the ownership of areas occupied by Agropalma.

In August 2020, the first instance court partially granted MPPA’s requests. The court recognized that the original acquisition documents of the farms later acquired by Agropalma were false, annulled them and cancelled the farms’ registrations. However, to the communities’ surprise and dissatisfaction, Agropalma continues possessing and exploring the areas. The court allowed Agropalma to continue trying to regularise the registrations through administrative proceedings filed before the Land Institute of Pará (ITERPA).

Agropalma states that their lands were acquired in good

faith from legitimate owners and possessors, including with the confirmation of

documentation by the competent bodies at the time of acquisition. It attributes

irregularities to “notary flaws” that compromised the legitimacy of the land

documentation of some properties, which it is seeking to rectify with the

competent authorities.

“It is absurd to see how courts allow this company to

continue to remain here although the court said that their land titles are

fake… Agropalma is the law here,” says Manoel Barbosa dos Santos, who has a claim

regarding his family’s lands.

Agropalma

appealed the decision, but the appeals have been dismissed by the second

instance court. While the local communities wait for the enforcement of this decision, they state that Agropalma

is waging a war to silence them.

José Joaquim dos Santos Pimenta, president of the ARQVA association, told Global Witness that he is constantly threatened by Agropalma’s employees. “Cars belonging to the company often stop in front of my house to monitor me.

Armed security men that work for Agropalma told me many times I need to speak less, otherwise they will have to shut me up. They deploy armed security to intimidate us.” Agropalma responded to Global Witness stating that none of the various social impact studies of their operations raised the presence of Indigenous nor Quilombola communities surrounding Agropalma plantations, nor did the studies identify that Agropalma had removed or incentivized removals of such peoples from their land.

José Joaquim dos Santos Pimenta, president of ARQVA Quilombola community association, and Fernando de Nazaré, member of Vila Gonçalves Quilombola community. Karina Iliescu

In the Quilombola communities of Vila Gonçalves and Balsa, 206 families feel wholly strangled by palm plantations all around them. According to community members, Agropalma has registered the lands in which they live, hunt, fish and plant for their survival as ‘legal reserves’, areas that rural landowners are required to set aside in their land holding to maintain native vegetation. The legality of this land registration is now being investigated by the Public Attorney’s Office from the State of Pará. To access nearby cities, community members have no choice but to cross dirt roads within the palm plantations.

The company has taken measures that amount to forcibly

restricting the communities’ ability to move: massive trenches have been dug

to make leaving more difficult; individuals need to go through gates – ruled

illegal by a Brazilian court – built by Agropalma;

they must present identity cards to company employees to cross the plantations to go outside this area; family, friends and –

on at least one occasion – even a hospital ambulance need to ask the company’s

permission to pass through.

The communities’ sacred, historical Nossa Senhora da Batalha cemetery is also out-of-bounds, which Serrão considers a particular humiliation. According to community testimonies, Agropalma also forbids residents from Balsa and Vila do Gonçalves to hunt, plant for subsistence and fish, alleging that their territory, as a legal reserve, cannot be degraded. Fish nets have been destroyed and people have been humiliated when crossing the river or attempting to hunt, leaving families without the means to subsist.

"It is a constant humiliation. I feel like an enslaved person, as my ancestors once were… Agropalma’s employees stand behind us all the time pointing guns at us while we try to pray for our deceased and clean their graves." Raimundo Serrão, ARQVA Quilombola community leader, 2022

In January 2022, the MPPA presented a formal recommendation to Agropalma that the company refrain from restricting communities’ access to their lands. MPPA also filed a complaint against Agropalma the following month. This complaint is not going forward due to the recent mediation agreement signed between the company and the communities, seen by Global Witness.

Responding to Global Witness, Agropalma defended the digging of trenches as a necessary measure to protect their legal reserve lands, but claims the trenches have since been removed. Agropalma noted that as holders of ‘legal reserve’ lands the company is responsible for maintaining their protection from deforestation and poaching, for example, on pain of fine or sanction. Agropalma also states that access restrictions were jointly agreed following the agreement with the community ion 17 February 2022. Agropalma denies restricting access to the Nossa Senhora da Batalha cemetery. It states that it abides by the agreement reached with ARQVA to allow access to persons contained on a list provided by ARQVA in June this year. Despite the agreement, community members report that the situation has not changed and they are still threatened.

Industry regulatory bodies seem to lack any awareness of the seriousness of the land conflicts. Agropalma is certified by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) voluntary industry initiative. In 2016, the body stated that that Agropalma has no history of unresolved conflicts. Community members asked by Global Witness do not recall ever being questioned by a RSPO-certification company or if there were investigations into Agropalma’s land. RSPO responded that there are currently no active complaints against Agropalma. In 2020, the RSPO Complaints Panel dismissed a complaint against the company, citing the land dispute as a matter for Brazilian courts.

Suffering from attacks daily, ARQVA’s president Pimenta says he is not afraid. He believes that if he is executed, others will fight in his place. “The fight won’t end until we can return to our land.”

Vila Gonçalves community members. Karina Iliescu

Upcoming presidential elections

The Bolsonaro government has favoured business interests to

the detriment of land and environmental defenders, particularly of Indigenous

and traditional communities. As President, Bolsonaro has made statements and implemented measures aiming to dismantle environmental policies and deprive

traditional communities of their rights.

Bolsonaro promised on taking office that no new land would be demarcated for traditional communities, a promise that he successfully kept. Under Bolsonaro’s government, institutions that protect traditional communities’ rights have been disempowered and defunded.

The Federal Government’s position regarding traditional people’s rights and land demarcation directly affects the situation in the northeast of Pará. “Government officials are advising companies and growers in our area to ‘get rid of’ those who are creating problems before another president takes over”, reports an Indigenous leader from Tomé-Açu. This is the message palm oil producers in the regions of Acará, Tomé-Açu and Tailândia have received, Indigenous and Quilombola community members believe.

BBF enjoys support from the powerful representative to the Pará State legislature, Deputado Caveira, who openly supports Bolsonaro’s candidacy. In a video in which he is addressing BBF employees, he stated that everything that is “not solved through legal means, will be solved with ‘gunpowder’, that is why President Jair Bolsonaro wants men like them [BBF’s employees] to be allowed to carry guns.” Deputado Caveira did not respond to requests for comment.

Regardless of who wins the October 2022 presidential election, rebuilding governmental institutions that protect traditional communities, demarcating land, increasing monitoring and expanding corporate accountability – all of which have stalled under the current government – are crucial to protecting land and environmental defenders’ lives.

Considering the current political environment, which is unfavourable to land and environmental defenders, and the fact that the conflicts in Pará are unlikely to cease even if Bolsonaro loses the elections, those who contribute to violating human rights should be held accountable.

Major consumer brands buying palm oil linked to human rights abuses

Global Witness asked traditional community members if they know where the palm fruits surrounding their lands go. No one had a clue. So where does it all go? Palm oil produced by Agropalma and BBF that is not consumed domestically is shipped to Europe, the United States and countries in Latin America such as Mexico, Colombia and Paraguay through American and European companies. The palm oil is bought by both multinational commodity traders including ADM, Bunge and Cargill and major consumer brands such as Danone, Ferrero, Hershey’s, Kellogg, Mondelez, Nestlé, PepsiCo and Unilever, according to the companies’ published lists of supplying palm oil mills (“mill lists”).

Global Witness identified 20 companies that

source palm oil, directly or indirectly, from BBF and Agropalma based on their

mill lists or on public information available on trade data systems.

Consumers in Europe, North America and elsewhere drinking Pepsi, eating breakfast cereals produced by Kellogg or enjoying chocolate from Mondelez, Hershey’s, Ferrero and Nestlé may have consumed palm oil produced in Pará at the violent cost of these communities’ livelihoods.

In September 2022, Global Witness contacted BBF, Agropalma and companies sourcing from them seeking comment on the allegations in this report.

Cargill states that it is aware of and concerned about the dispute in Tomé-Açú and Acará, and that it has been included in their grievance list, but they believe that the solution is not to stop sourcing from the company. Cargill further stated that an ‘action plan’ is in place to ensure BBF adheres to Cargill’s Policy on Sustainable Palm Oil, reporting that “BBF has continued to make progress against it.” Cargill reports that Agropalma has also “implemented an action plan for improvement.”

In April 2022, Kellogg stated concern about the communities’ allegations and recognized the need for action. It later reported further communication with BBF, its indirect supplier, and is co-sponsoring a program to support BBF in “acceptable methods of conflict management.” Kellogg is monitoring the Agropalma case.

Ferrero stated that it is engaging with Agropalma via its grievance management procedure, noting that Agropalma commissioned an “independent assessment …[by] Instituto Peabiru.” It also shared a 2021 assessment of Agropalma by a certification company, which declared “since the complaints and grievances procedure was established there has been no record of conflicts with communities” and that “Agropalma and partner producers’ areas are private and are not used in community areas."

Agropalma’s “no trespass” sign in Tailândia. Karina Iliescu

Mars reported that it engaged with Agropalma in March 2022, and reengaged the company following Global Witness’ request for comment, asking for further clarification, and encouraging the company to investigate the allegations. Partnering with Verite, Mars supports Agropalma to conduct specific work on community grievance mechanisms and management of grievances.

Nestlé responded to Global Witness that it takes the allegations regarding Agropalma and BBF seriously. Nestlé reports that it has reached out to Agropalma to investigate and encourage them to address the situation with the local communities and that it will conduct responsible sourcing audits. Nestlé has engaged with its tier-1 supplier which sources palm oil directly from BBF, reporting that this supplier is working on an action plan with BBF to address the situation.

AAK noted that it has reached out to its indirect supplier Agropalma for comment; and to its direct suppliers that purchase directly from Agropalma; and engaged sustainability service providers to weigh in on the allegations.

Citing its Sustainable Palm Oil Policy and Supplier Qualification Process, Bunge responded that all its business operations with suppliers “are legal and in compliance with Brazilian legislation and company procedures.” It is monitoring the Agropalma case.

Hersheys sources palm oil from Agropalma and BBF indirectly via traders Cargill and AAK. Hersheys is monitoring the BBF situation via Cargill’s grievance investigation. Hersheys has also initiated a grievance investigation on Agropalma with AAK and Cargill.

Unilever reports that it is conducting a detailed assessment of the situation involving Agropalma and cited its Responsible Sourcing Policy and its People and Nature Policy. It sources palm oil from BBF indirectly, and reports it is engaging its direct supplier who sources palm oil from BBF to investigate the allegations.

Upfield stated that it does not source palm oil from BBF; its most recent mill list lists Agropalma as a supplier. In line with its policies and procedures, Upfield said it would review the issues raised in this report and engage its direct suppliers sourcing from Agropalma during its quarterly supplier engagement process, if necessary.

Although this is our land and this is where we have been living for generations, the only people profiting from our harm are the large companies. - Paratê Tembé, Indigenous leader, 2022

General Mills responded that it is tracking the allegations against BBF and Agropalma via its grievance process, citing its Global Responsible Sourcing program and Supplier Code of Conduct.

Danone stated that they source palm oil indirectly from Agropalma, calling the allegations inexcusable and extremely alarming. The company has launched an investigation through its grievance mechanism to deal with the matter with a view to working with its supply chain to resolve or suspend activities.

Pepsico does not have a formal comment on the allegations. The company is looking into the information by establishing whether it has sourcing links to BBF through its direct suppliers, and by engaging Agropalma on the allegations.

ADM including Stratas Foods and Olenex, Friesland Campina, Mondelez, Olvea, and PZ Cussons did not respond to Global Witness’ requests for comment.

The long-running land conflicts linked to BBF’s and Agropalma’s plantation operations are escalating. While individuals are being tortured, and communities are living with fear of execution, BBF and Agropalma continue to profit and trade internationally with some of the biggest household names.

Urgent call for action to prevent further violence and other attacks

International business and human rights standards require a company to identify, prevent, mitigate and remedy human rights violations linked to its business operations, including any abuses arising through its global supply chains.

Global brands who purchase palm oil produced in areas linked with human rights abuses are failing in their responsibilities to prevent human rights abuses and other serious harms in their operations and supply chains.

The fact that all multinational companies who responded to Global Witness claim to be aware of the conflicts in their Brazilian palm oil supply chains and continue to purchase palm oil from BBF and/or Agropalma indicate that they have completely failed to prevent or mitigate human rights abuses occurring in this region of Pará.

Turiuara camp in the middle of BBF's palm plantations. Cícero Pedrosa Neto

Global Witness calls on AAK, ADM, Bunge, Cargill, Danone,

Ferrero, Friesland Campina, General Mills, Hersheys, Kellogg, Mars, Mondelez,

Nestlé, Olenex, Olvea Vegetable Oils, PepsiCo, PZ Cussons, Stratas Foods,

Unilever, and Upfield to act immediately to:

- Ensure that BBF and/or Agropalma urgently prevent any further harms to members of any community within or surrounding their palm plantations, and to terminate contracts with them if they do not do so

- Take all necessary action to remedy the harms already suffered by the communities

- Ensure that palm oil is only sourced from suppliers who follow relevant international business and human rights standards

In February 2022, the European Commission released a draft law to promote corporate accountability by requiring companies to assess their impacts on people and the planet. The Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive – if passed – will require companies operating in the EU to identify, prevent and mitigate human rights and environmental risks associated with their activities, and remedy harms that they have caused. Crucially, if passed, this law could hold companies liable in European courts if they fail to comply.

While this Directive could be a game-changer in improving corporate responsibility, Global Witness has emphasized that the draft must be strengthened to truly protect communities that suffer from corporate abuse. The draft currently includes loopholes and shortcomings that could allow business to continue as usual, with little real change. Among many issues, the draft does not require companies to engage with affected communities, including land and environmental defenders and Indigenous communities. The draft merely states that they should be consulted only “where relevant”. With growing violence against affected communities, as shown in this report, it is essential that the legislation mandate meaningful engagement with impacted and potentially impacted communities as part of a company’s ongoing due diligence processes.

Global Witness recommends that the European Union strengthen the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive in line with civil society recommendations, including by mandating that companies engage affected communities in an ongoing, safe, and inclusive manner. This process is essential to ensuring that human rights and other abuses such as those taking place in BBF and Agropalma’s operations are prevented and remedied.