Imagine that you and your colleague are on a lunch break and both of you are scrolling through your Facebook feeds at your desks. You work in the same company and have similar roles, responsibilities, and experience. So, what’s going on if your colleague sees an ad for an interesting, well-paid job that you’d love to get the chance to apply for, but you haven’t seen it? He mentions it to you, you refresh your feed and scan the ads again, but it still doesn’t appear.

It appears that you haven’t been shown the ad.

The ads that we see on Facebook completely depend on the data it collects about us both on and off the platform. Using thousands of data points - including characteristics such as age and gender – the platform draws inferences about each user, profiling every one of us, and then charges advertisers for the ability to target particular profiles and deliver ads to their feeds.

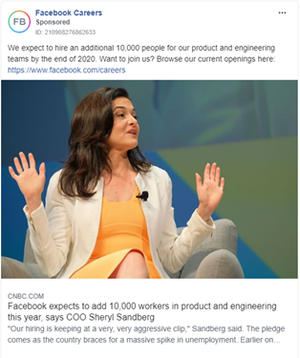

If you are a woman and over 55 years of age and used Facebook in April 2020 it could be that one of the ads you didn’t see was this one, from Facebook itself.

This job advert was posted by Facebook on its Facebook Careers page alerting people to a series of job openings at the company. The advert used to be available on this link on the Facebook Ad Library but is no longer there.

In April 2020 this ad for job openings at Facebook was seen by more than half a million people in the UK. Yet only 3% of the people who saw the ad were 55 years or older, despite the fact that nearly 20% of Facebook users in the UK are in this age bracket. Men were 62% more likely to be shown the ad than women, and the demographic that saw the ad most frequently was men between 25 and 34 years of age.

Facebook’s Ad Library gave us a demographic breakdown of who saw it but no explanation as to how and whether they had specifically targeted the ad at a younger and male demographic, or whether the targeting was caused or delivered by the platforms’ so-called ‘ad optimisation’ algorithm, the automated means by which Facebook decides which of the people targeted should be shown an ad.

We had found a troubling and potentially discriminatory result and decided to take a deeper dive to understand if this was a one-off or reflected a systemic problem within Facebook’s advertising offer.

We created two job ads with the intention of using different forms of discriminatory targeting: one ad was targeted to exclude women, the other to exclude people over the age of 55.

Before we could submit these test ads to Facebook for approval, we were required to comply with Facebook’s non-discrimination policy. We ticked the box and submitted the ads.

Facebook accepted both ads for publication. The policy is evidently self-regulatory and self-certified, and it seems from our test that Facebook will accept patently discriminatory targeting for job adverts. In order to avoid advertising in a discriminatory way, we pulled the ads from Facebook before their scheduled publication date.

We then went on to publish four further test adverts. This time we did post them on the platform, and they contained links to real job vacancies for a range of trades and professions: mechanics, nursery nurses, pilots and psychologists. Unlike the previous tests we made no stipulations about the profiles we wanted reach other than that they should be posted to adults in the UK.

When posting an ad on Facebook’s platform you can manually select the targeting yourself, use Facebook’s ‘optimisation for ad delivery’ system which automatically identifies who should see the ad based on different objectives, or a combination of the two.

For example, if you want your ads to increase awareness of your brand, Facebook’s ‘optimisation for ad delivery’ system will aim to maximise the total number of people who will remember seeing your ads.

Facebook provides advertisers with different objectives for its ad delivery algorithm We opted for Facebook’s ‘Traffic/Link Clicks’ objective which the platform says ensures that ads are delivered to “the people who are most likely to click on them” as that is the objective people advertising links to job vacancies would be likely to use.

Because we specified no targeting criteria ourselves for these ads, the people who were shown them were therefore decided entirely by Facebook’s algorithm.

And the results?

- 96% of the people shown the ad for mechanic jobs were men;

- 95% of those shown the ad for nursery nurse jobs were women;

- 75% of those shown the ad for pilot jobs were men;

- 77% of those shown the ad for psychologist jobs were women.

Even though Facebook requires advertisers to confirm that they will not discriminate when posting job ads, its own ad delivery system appears to operate in a discriminatory manner.

Remember

our imaginary scenario? When you didn’t see an advert that your colleague did,

it wasn’t because a bug in the system prevented you, it may have been the

system in action.

Facebook’s business model of profiting from profiling appears to replicate the biases we see in the world, potentially narrowing opportunities for users and preventing progress and equity in the workplace.

This is not the first time that questions have been raised about the discriminatory impact of Facebook’s ad targeting.

Our evidence tallies with the findings of Algorithm Watch and academics who have also shown that Facebook’s ad delivery algorithm is highly discriminatory in delivering job ads in France, Germany, Switzerland and the US. In fact, recent investigations in the US have shown that Facebook’s ad delivery system is skewed by gender, potentially excluding swathes of women from seeing job opportunities even when they are equally as qualified as the men that are being selected by Facebook to see certain ads.

In March 2019, the US Department of Housing sued Facebook alleging that their ad delivery algorithm discriminates. They also allege that even if advertisers try to circumvent this by targeting ads at an unrepresented group, then Facebook’s algorithm will not deliver the ad to those people. The case is ongoing.

Meanwhile, The New York Times and ProPublica have shown that big companies, including Facebook, have excluded older people from their job ads on Facebook in the US and The Sunday Times has done the same in the UK.

Civil rights organisations sued in the US and in 2019, as part of the settlement of five of the lawsuits, Facebook prevented advertisers from targeting housing, employment and credit offers to people by age, gender or ZIP code - but only did so in the US and, later, Canada.

Faced with the results from our adverts, and in light of the evidence uncovered in other jurisdictions, we shared our findings with Schona Jolly QC, a leading human rights and employment lawyer who subsequently authored a submission to the UK Equality and Human Rights Commission on our behalf.

In her assessment, “Facebook’s system itself may, and does appear to, lead to discriminatory outcomes” and further, that “the facts as found and collated by Global Witness…give rise to a strong suspicion that Facebook has acted, and continues to act, in violation of the Equality Act 2010”.

We are therefore asking the EHRC to formally investigate Facebook’s compliance with British equality laws.

We are also asking the UK Information Commissioner’s Office to weigh in on the compatibility of Facebook’s advertising products with the General Data Protection Regime. If it is the case that Facebook are in breach of the UK’s anti-discrimination legislation, they may also fall foul of the GDPR’s requirement for data to be processed ‘lawfully’ and ‘fairly’.

A Facebook spokesperson said "Our system takes into account different kinds of information to try and serve people ads they will be most interested in, and we are reviewing the findings within this report. We've been exploring expanding limitations on targeting options for job, housing and credit ads to other regions beyond the US and Canada, and plan to have an update in the coming weeks."

In June this year Facebook launched a defence of personalised targeted advertising, claiming that “personalised ads level the playing field for small businesses by helping those ideas reach new customers”. Good ideas, they said, “deserve to be found”.

We think good candidates deserve to be found too. Can Facebook say the same?

Recommendations

We are calling for:

- The UK Equality & Human Rights Commission to investigate whether Facebook’s targeting and ad delivery practices breach the Equality Act (2010).

- The UK Information Commissioner’s Office to investigate whether Facebook’s ad delivery practices breach the GDPR.

- Governments to require tech companies that use algorithms that have the potential to discriminate against users to assess and mitigate those risks to the point that they’re negligible. The risk assessments should be made public and overseen by an independent regulator with the powers to conduct their own audits.

- Governments to require tech companies to make the criteria used to target online ads transparent, at the same level of detail that the advertisers themselves use.

- Facebook to roll out the changes it has made to housing, job and credit ads in the US and Canada to the rest of the world. While these changes are not sufficient to address any discrimination caused Facebook’s own algorithms, they are a start in addressing discrimination by advertisers.